The Grammy Awards are justly famed for getting it wrong a whole lot of the time. But one longstanding category, Best Music Film, has quietly but frequently gotten it right.

In 1984, when the category debuted, it was called Best Longform Video, intended for both collections of MTV-ready clips—such as the inaugural winner, Duran Duran, a compendium of the band’s first eleven videos—and documentaries such as the Hal Ashby-directed Rolling Stones concert film Let’s Spend the Night Together, also nominated in ’84. The rise of music-documentary production, particularly once the DVD came along, has skewed the category toward that end since the millennium turned—and a larger number of those films also screened theatrically, thanks to all-music-film festivals such as Sound Unseen in Minneapolis and Austin. Accordingly, in 2014, the Grammys changed the name of Best Longform Video to Best Music Film. (Please note—the years cited refer to when Grammys were awarded, not the year of a film’s, or recording’s, release.)

The added gravitas of that name change makes sense. Over the past twenty years, this Grammy has gone to films by major directors like Martin Scorsese (Bob Dylan’s No Direction Home, 2006), Peter Bogdanovich (Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers’ Runnin’ Down a Dream, 2009), and Ron Howard (The Beatles: Eight Days a Week, 2017). Several theatrically released Best Music Film winners were also awarded the Best Documentary Oscar, including 20 Feet from Stardom (2015), Amy (2016), and Summer of Soul (2022), while streaming projects like The Defiant Ones (about Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine, 2018) and Homecoming: A Film by Beyoncé (2020) were both nominated for several Emmys apiece.

That’s a notable group of films, period, and it made us curious about the upcoming Grammy nominees in the category. What do these Best Music Film contenders have to teach us? Do they really work as filmmaking, or simply as promotion? Or as, you know, both, since every single one features a production credit for its artist(s) and/or their families. They’re reviewed alphabetically by title.

American Symphony (dir. Matthew Heineman)

This documentary is evidently stagy—at one point, we see the jazz keyboardist Jon Batiste lying in bed, putting his bible on his chest and folding his hands over it as he slumbers. Maybe he does that every night, but really, so neatly? Actually, conceivably so—Batiste, a New Orleans native who led the band on Stephen Colbert’s show for seven years, always seems to be on. He also comes off as genuine—a born performer who knows how to modulate for the setting. He may have attended Julliard for seven years, but Batiste is a man of the people. So of course, he’s Grammy-bait. This film begins around the time he received a commanding eleven nominations in 2022; he wound up winning five, including Album of the Year for We Are. The film mainly concerns Batiste assembling a symphony while also helping his longtime partner, the writer Suleuja Joauad (they actually marry on screen) through intense chemotherapy sessions, after her cancer returned following ten years’ remission—and, in a cruel twist, resurged a third time the night he won his Grammys. Those scenes are wrenching; some of the others, less so. Batiste radiates positivity even when he’s telling us otherwise; as he describes an early career full of “pushback, pushback, pushback,” we see him embracing the doorman of a large building—not typically the chummy type, mind you—which is about as far from “pushback” as it gets. All of it is photographed up close with a seemingly floating camera; at times, a little too lovingly. The very real problems the couple faces here do not preempt this film from being, at times, simply indulgent. But Batiste has delivered Grammy surprise wins before. It’s possible he could do it again—with a doc in which he wins five others, which would be some kind of Grammy ouroboros. (Netflix)

The Greatest Night in Pop (dir. Bao Nguyen)

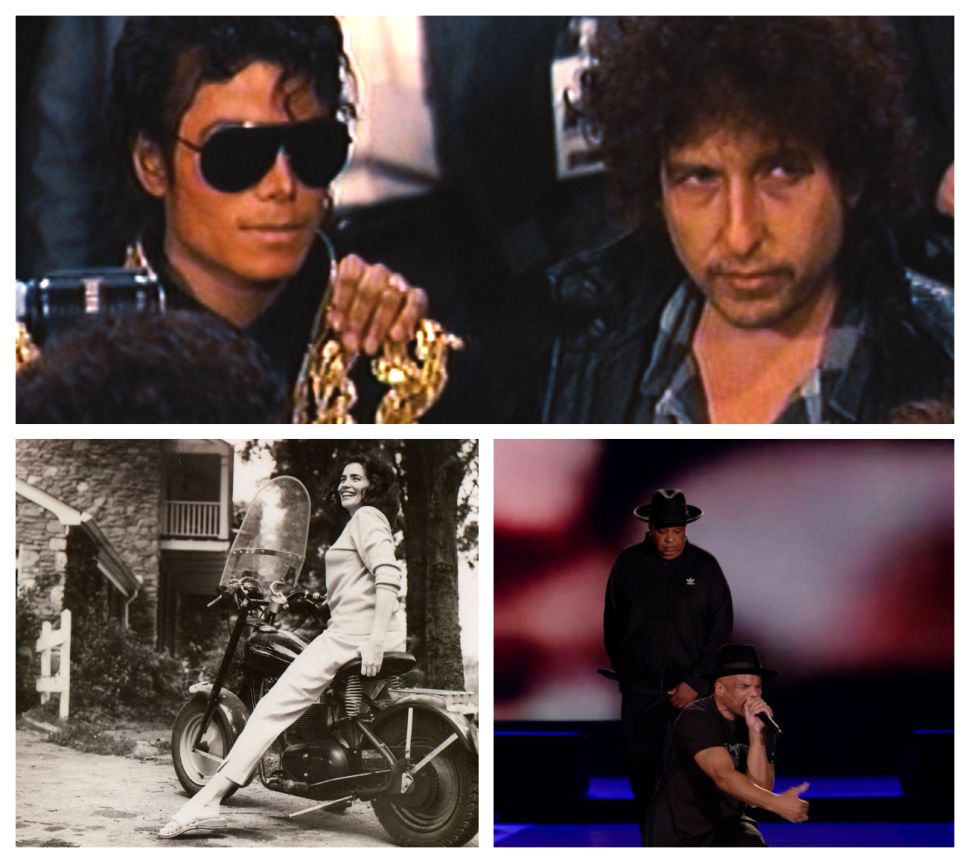

This, too, would be Grammy eating itself—awarding a film that chronicles a previous major award winner. But really, it’s Grammy Rule No. 1: Whoever hires the most session players, wins. Think of Frank Sinatra, think of Christopher Cross, think of Daft Punk. And most of all, think of Quincy Jones. Once, when asked if he ever thought about his 28 lifetime Grammy wins, Jones paused half a second and said, through a cat-with-canary smile, “I think about the 52 I lost!” Jones wasn’t involved in making this documentary about USA for Africa’s “We Are the World”—the Grammys’ Record of the Year in 1986, which Jones did produce. But his spirit and memory will surely loom large over the 2025 ceremony—and maybe the balloting. The presiding eminence in The Greatest Night in Pop is Lionel Richie, the film’s co-producer and lead talking head. He tells stories of Michael Jackson’s scary menagerie with great dry wit. (Jackson and Richie co-wrote the song.) Anyone who recalls “We Are the World” knows how ubiquitous, and widely covered, it was in its time. But this forty-year look-back is genuinely riveting even if you already knew many of the project’s details going in. It’s one thing to read about these force-of-nature performers each taking their turns wowing each other; it’s quite another to watch it in real time, to see and hear this ultimate summit meeting in its proper context. The documentary is far, far better and richer than the record ever was. And anyone who recalls Stevie Wonder’s hall-of-fame turn as Saturday Night Live host in 1983 will savor his role as the event’s comedian-in-chief, from his being finally ready to co-write the song while the demo was being cut, to his coaching Bob Dylan through his lines—by brazenly imitating Bob Dylan. (Netflix)

June: The June Carter Cash Story (dir. Kirsten Vaurio)

June Carter Cash was a child star of a family act—the Carter Family, country royalty—who went briefly out on her own to study acting in New York. But she eventually came back to Nashville and married Johnny Cash, also country royalty, and put her solo career on hold—though still performing with him regularly—until a late-life career surge, recording two acclaimed and Grammy-winning albums shortly before her death in 2003. This loving history, produced by her kids Carlene Carter and John Carter Cash, has plenty of eye candy—live and TV performances, private video, candid photos, the works—and what impresses in all of it, old and young, is June’s startling presence—her restless intelligence as well as her arresting blue eyes. But there’s not quite enough here to convince a newcomer she belongs in the pantheon on her own terms—one featured song, “Back in My Rock ’n’ Roll Years,” is an outright horror—and ending the film with a shot of a freakin’ rainbow in the sky is really pushing it. Not even American Symphony does that. (Paramount Plus)

Kings from Queens: The RUN DMC Story (dir. Kirk Fraser)

RUN DMC, as it is apparently now styled, are the fulcrum of hip-hop’s story. As RUN (Joseph Simmons) and DMC (Darryl McDaniels) and, in archival footage, Jam Master Jay (Jason Mizell), say again and again, the group caught on because they were just like their fans—dressed in street style (unlaced Adidas, basic black, gold chains) that anyone could aspire to. The genre’s first superstars, they were also the first to attract widespread notoriety (thanks to gang violence, unrelated to the group, at a 1986 show in Long Beach, California) as well as achieve chart dominance (their cover of Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way” hit the top five in 1986). RUN DMC modeled the hip-hop basics—a DJ rocking two turntables while a pair of MCs traded first-rate rhymes—after four years of recordings that had aspired to R&B rather than spotlighting what made the genre unique, therefore breaking it wide open. At three parts in two and a half hours, Kings from Queens does a creditable job of opening the group’s story up—the personal camcorder footage in this one is very welcome, particularly some proud-papa family video by Mizell of his wife and sons. It also fills in their context, as the big dogs of a scene that coalesced around Def Jam Records co-founders and producers Russell Simmons (RUN’s older brother) and Rick Rubin: “He had a drum machine full of hits,” the former says about meeting the latter. Jam Master Jay’s murder in 2002 is the finale’s centerpiece, tenderly handled and heartrending. And seeing RUN and DMC performing during the Hip-Hop 50 show at Yankee Stadium, intercut with their younger selves, is enough to make a fan verklempt. As DMC puts it early in the series: “We changed the fucking world.” (Peacock)

Stevie Van Zandt: Disciple (dir. Bill Teck)

Steven Van Zandt, man of many nicknames (Miami Steve, Little Steven), has made some good music (particularly with Bruce Springsteen) and done some good acting (particularly on The Sopranos), but his Rock & Roll True Believer schtick has long since become background noise. With a subtitle like Disciple—and wait, he’s Stevie now?—plus a two-and-a-half-hour run time (as long as the three-part RUN DMC doc above), this reviewer feared the worst. Here’s the nice surprise—this is a straightforward retelling of a rich, well lived life. The film opens, daringly, with a none-more-pop-metal ‘80s video by Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul that makes the moussed hair and jazzercise sweatbands of The Greatest Night in Pop look timid and reserved. This applies to just about everything Van Zandt is depicted wearing in the film—a proud peacock he is. Another Greatest Night analogy: Van Zandt was the musical mind behind Artists United Against Apartheid’s “Sun City,” a sharp turn from the bromides of “We Are the World” to hard political specifics, the direction Van Zandt’s own work took after he set sail from the E Street Band in the mid-’80s. He went, as Springsteen puts it in his testimonial, “from no politics to all politics.” (Bruce, incidentally, also put out his own doc this year on Hulu, Road Diary.) Van Zandt swerved again after the ‘80s ended: “I realized I didn’t want to be a politician,” he says. Instead, as he puts it, “I walked my dog for seven years.” He re-found himself piece by piece—a publishing deal, some Hollywood commissions—before The Sopranos came along and opened a series of new lanes, leading to his satellite radio stations, Underground Garage and Outlaw Country; a rejuvenated touring schedule; and reuniting with Bruce. The doc calls in some big guns—Keith Richards, Paul McCartney, Bono, Eddie Vedder—and they make the case for Van Zandt in rather convincing terms. (Max)

The 67th Annual Grammy Awards airs on CBS, Sunday, February 2. A complete list of nominations is available here.