The exhibition “EXILS – Regards d’artistes” at the Louvre Lens opens with a small folded paper boat in a glass vitrine, ‘SOS Méditerranée’—a humanitarian organization—and ‘#TogetherForRescue’ emblazoned on its side. Similarly acknowledging the contemporary migrant crisis in objecthood, a synthetic-and-cotton backpack forged from life vests collected along shorelines of the island of Lesvos can be found elsewhere in the show (the project of Lesvos Solidarity, a Greek NGO supporting refugees).

Behind the paper boat, French artist Richard Baquié’s 1989 stainless steel ensemble of lettering spells out across a wall, Nulle part est un endroit” (“Nowhere is a place”). Is this phrasing pithy or empty? This show has pulled together 200 works on a charged subject but en masse, they don’t make collective sense because the curator uses too broad a definition of exile to possibly arrive at a coherent point about displacement in today’s world.

Starting with Biblical scenarios and Greek myths, then broadening to contemporary placelessness, this sweeping breadth ultimately has a flattening effect. As Edward W. Said wrote in Reflections on Exile in 1984 that “the difference between earlier exiles and those of our own time is, it bears stressing, scale: our age—with its modern warfare, imperialism and the quasi-theological ambitions of totalitarian rulers—is indeed the age of the refugee, the displaced person, mass immigration.” This salient point is not addressed meaningfully in the exhibition, where Odysseus is given the same narrative arc as modern asylum seekers.

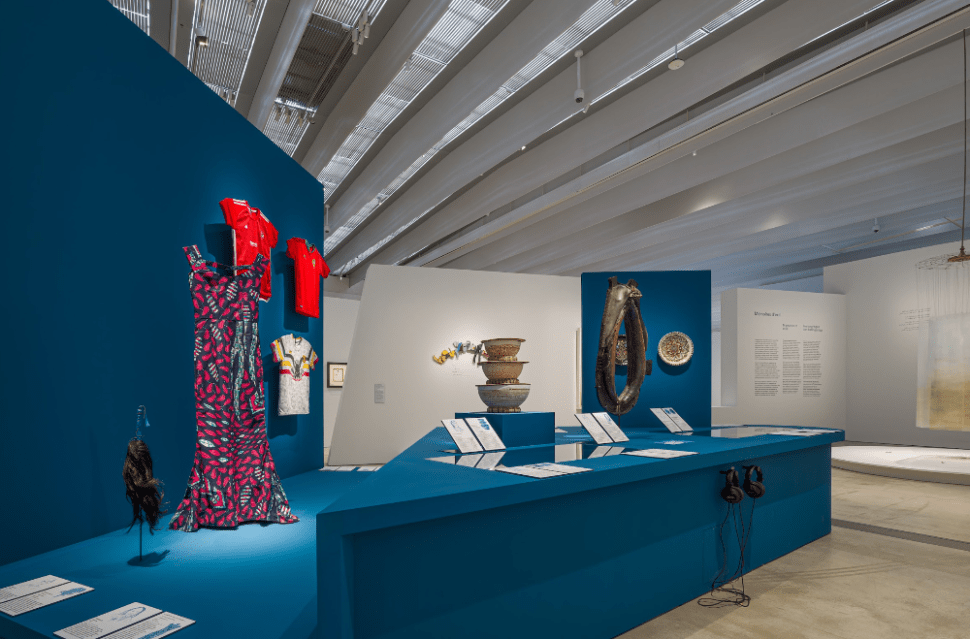

Moving on, the visitor encounters a 2013 installation by Cameroonian-French artist Barthélémy Toguo, in which fabric bundles and plastic bags are stacked high and tethered to a bicycle—echoing the work of Korean artist Kimsooja and her 2007 video Bottari Truck – Migrant further in, in which a woman on a wagon loaded with bundles fashioned from bedspreads rides through Paris to reach the Saint-Bernard church (a site that once sheltered undocumented migrants brusquely dispersed by the police in the mid-1990s). Materiality and volume—the heft of belongings and how they articulate our identity—become an uneasy burden when fleeing is imperative. Toguo has another installation in the show—New World Climax, made in 2001 out of the kind of jumbo rubber stamps used at passport control, underscoring the outsized distress of customs and borders.

In a less matter-of-fact piece, Portuguese artist Marco Godinho’s Written by Water (2013/2024)—which was part of the 2019 Venice Biennale’s Luxembourg Pavilion—showcases hundreds of splayed-open blank notebooks arranged in a neat formation. Having been dipped in the Mediterranean from coastal locations spanning Gibraltar to Marseille, the rumpled pages poetically evoke the fraught fragility of passage in this body of water.

Among the various video pieces, Albanian-born Adrian Paci’s 2007 short film Centro di Permanenza Temporanea (Temporary Detention Center) is effective and uncomfortable: it shows dense clusters of people waiting on a mobile staircase, the kind usually leading to a plane. None ever arrives, and the crowd stands inert and cramped, headed nowhere in a Waiting for Godot-style folly.

SEE ALSO: Lightmachines, Digital Realities and the Art of Technological Nostalgia at Tate Modern

Gaza-born Taysir Batniji’s Untitled (1998-2021), a suitcase filled with sand, feels especially bleak to look upon in the context of the ongoing Middle Eastern conflict, rippling with the symbolism of contested lands. In the neighboring region, Syrian artist Khaled Dawwad’s polystyrene and iron maquette (2018-2021) of the devastated Ghouta area near Damascus—ruined by wartime bombardments and the release of sarin gas ordered by Bashar al Assad—is a heartbreaking sight, urban infrastructure and its human imprint rendered irreparable rubble.

Bridging together various sections of the exhibition in a central pivot point, a library area presents books by, amongst others, Chilean poet-diplomat Pablo Neruda, German-American historian and philosopher Hannah Arendt, Martinican writer Édouard Glissant, Martinican poet and politician Aimé Césaire, French-Iranian cartoonist Marjane Satrapi and Palestinian poet-author Mahmoud Darwish. Here, intellectual reflection and literature on exile are consequential and bring forth a plurality of visions.

In contrast, another section of the exhibition, dubbed “Internal Exile,” is cringe-level maladroit. The sheer absurdity of including French artist Eugène Delacroix in an exhibition about exile because he “couldn’t find his place in society after the French Revolution” and moved 30 kilometers outside of Paris to paint bouquets seems like an affront to anyone who has been displaced and reflects a certain tone-deafness of the curator (a French white woman). “The artists presented in this exhibition do not view exile from a distance,” she writes in the wall text—one would hope not, and yet this inclusion dilutes the weight of the theme. As Said noted: “Anyone who is really homeless regards the habit of seeing estrangement in everything modern as an affectation,” and, further, “much of the contemporary interest in exile can be traced to the somewhat pallid notion that non-exiles can share in the benefits of exile as a redemptive motif.”

The exhibition concludes with a phenomenon manifested on France’s own soil, not terribly far from Lens itself: the Calais Jungle, located at the northern tip of the country, where nine thousand refugees were detained from 2015 until the camp was dismantled in 2017. This port city has been a byway for displacement throughout Europe for centuries—there have been other camps in Calais over previous years, but this particular shantytown drew global media attention during the height of the European migrant crisis; currently, there is a policy of “no fixation points” for migrants in the region, an attempt to stop large camps from re-forming. In the exhibition, photos by Gilles Raynaldy of Sudanese migrants and their makeshift habitats are presented, adjacent to Bruno Serralongue’s examination, a decade earlier, of the living conditions of refugees trying to cross the Channel to England. Frank Smith’s 2023 Les Films des Objets (Object Films) is a looping series of twelve short films spotlighting items quietly placed on the dunes of Fort Vert. The landscape bears no traces of its recent refugee history, simply showcasing a backdrop of calm sands and blue waters.

The exhibition crystallizes the incredible privilege of remaining secure in the land you’re from and the luxury of choosing where you live—something the average fortunate European viewer has, likely, rarely had to grapple with. What art can do to relay the agony of diaspora and displacement may be relatively insubstantial. Still, it serves as an essential reminder that rootedness is not to be taken for granted in this chaotic world.

“EXILS – Regards d’artistes” is at the Louvre Lens through January 20, 2025.