Matisse didn’t just paint pictures; he portrayed emotion with color. His pictures convey a lightness of being with their bold outlines and ornamentation. They vibrate with liveliness. Especially with his figures, there is an openness, ripe with vitality. In his odalisques, he captured an intimate understanding of femininity—the unspoken grace of a folded body, the languor of lounging, the elegance of stillness. Matisse once said, “Painting the human figure is the best way for me to express what I might call my own particular religious feeling about life.” If only traditional religion were that free!

In our world of digital overstimulation, standing in front of a Matisse is electrifying. His are joyous paintings, a celebration of life filled with freshness. You can sense the sheer pleasure, the delight in his sun-drenched paintings. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire said it well: “Like the orange, Henri Matisse’s paintings are the fruit of dazzling light.” This light and the colors it enlivened became his signature. He strove to capture “colors pushed to their limits” and was a fearless creator who honored his singular view of reality and pursued relentless reinvention, even through two World Wars.

A portrait of the artist in brief: Born in 1869 to a modest grain merchant, Matisse seemed destined for a life in law—until an unexpected intestinal illness at age 21 forced a year of convalescence, during which his mother gifted him a box of paints that would change the course of his life. Three years later, he studied with the symbolist painter Gustave Moreau. His patrons included Gertrude and Sarah Stein and the American educator Albert C. Barnes, who founded the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. Matisse designed the windows, clerical vestments and the door for the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence based on his cut-outs. In 1952, he established the Matisse Museum to contain his work. Despite a lifetime of severe health issues, like duodenal cancer, he continued to create prolifically: more paintings, prints, sculptures and drawings. Of his cut-outs, he said, “Cutting straight into colour reminds me of what a sculptor does to his stone.” Matisse died in 1954 at age 84 in Nice, France.

A major retrospective, “Matisse—Invitation to the Voyage” at Fondation Beyeler in Riehen, near Basel, Switzerland, features more than seventy works from 1900 through to the 1950s installed chronologically, ending with his cut-outs. A multimedia space explores Matisse’s travels to foreign countries using animated historical photographs and wall panels. Films of his studio and creative process offer insight into his working methods and the intensity of concentration.

Senior curator Raphaël Bouvier described the exhibition’s reception as extraordinary, noting that over 100,000 visitors arrived within the first fifty days—a testament to Matisse’s enduring appeal. When asked how curating the show changed how he sees Matisse’s work, Bouvier told Observer that it opened his eyes to Matisse’s extraordinary artistic development: “He is one of the few artists who reinvented himself in his final work period when he started to create his iconic cut-outs, the synthesis of his artistic work. His late cut-outs, which are seminal for young, future generations of artists, are especially touching. They show the power of art and creativity that can rejuvenate and innovate.”

SEE ALSO: At the Louvre Lens, Imparting the Albatross of Displacement Through Art

From the South of France to North Africa, Russia, the South Pacific, and crossing the USA from New York to California, Matisse found inspiration in the different cultures, landscapes and the unique light of each place. He dreamed of an art filled with balance, purity and serenity—free from troubling subject matter; an art with a “soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair that provides relaxation from fatigue.”

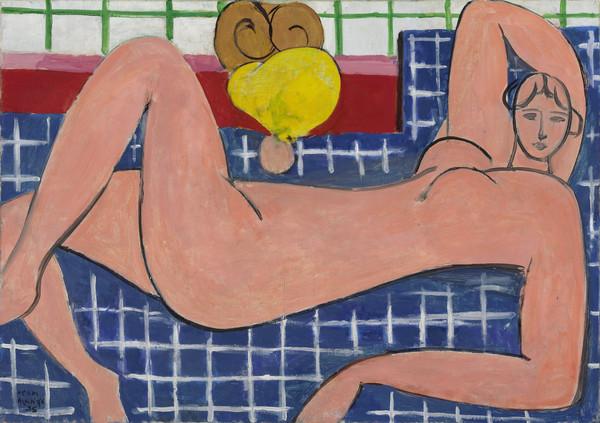

Late in his life he said, “I have always tried to hide my efforts and wanted my work to have the lightness and joyousness of a springtime that never lets anyone suspect the labors it has cost.” He spent, by way of example, six months working on The Pink Nude. He believed, like so many great artists before him and since, that drawing was fundamental and essential for a lifetime of work. He often spent months making hundreds of superimposed sketches, one on top of the other, to refine a composition. Drawing, he’d say, is simply concentrated painting.

Matisse’s radical sense of freedom, exuberance, bold use of color and obvious child-like wonder make one feel alive. His paintings are alive, joyfully. As he once said, “You have to know how to preserve that freshness and innocence a child has when it approaches things. You have to remain a child your whole life long and yet be a man who draws his energy from the things of the world.”

“Matisse—Invitation to the Voyage” at Fondation Beyeler closes on January 26.