Introduction

A spate of recent violent and high-profile incidents involving individuals with documented, unmanaged mental illness and substance use disorders has drawn significant public and press attention. In response, Governor Kathy Hochul and Mayor Eric Adams have both emphasized the need to improve policies that support individuals with serious behavioral health needs and address public safety concerns. Although the focus of the most recent debate is about rules for involuntary commitment, behavioral health experts and many policymakers agree that a comprehensive solution involves addressing the entire continuum of care.

Effective care management is widely recognized as essential for individuals with complex needs, as navigating the intricate systems of physical and behavioral health services, managed care plans, social services, housing, and sometimes the criminal justice system is challenging, particularly for individuals with mental illness or substance use disorders. Nevertheless, the subject of “care management” is arcane and generally, not well understood.

The purpose of this Policy Brief is to provide an in-depth description of the existing care management infrastructure in New York and trace its evolution to its current form. The current care management system is rife with overlapping programs and confusion of roles. Accountability is complicated by limited insight into outcomes and a bureaucratic structure that divides responsibility among multiple governmental agencies, including the New York State Department of Health (DOH), the Office of Mental Health (OMH), and the Office of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS).

The issue of care management in behavioral health is also a case study in bureaucratic inertia. In 2012, the fundamental structure of State oversight shifted to replace programs under which OMH contracted directly with care management agencies (CMAs) – the organizations that directly perform care management services – with a system under which new entities called “Health Homes”, regulated by DOH but licensed and reimbursed as Medicaid service providers, would contract with managed care organizations. In this new model, Health Homes contract directly with CMAs, who, as a result, have no direct contractual accountability to the State.

Health homes received 90% of their funding from the federal government for the first eight quarters of the program, compared to 50% from the federal government under the care management programs they replaced, which made adoption of the health home model fiscally attractive. Over the years, many have questioned whether the Health Home model is, in fact, superior to the previous model, but the technical nature of these programs and the force of inertia has prevented a rethinking of fundamental decisions about organizational structure.

The current political focus on issues involving the behavioral health system provides an opportunity to reconsider many of these issues as they relate to care management. Hopefully, this Policy Brief can help inform that discussion.

Background

Individuals with complex behavioral health needs require not only timely access to quality behavioral health services but also coordination of medical care and social services, including support with finding housing and identifying and enrolling in government programs for which they are eligible. It is difficult for individuals to effectively and efficiently manage their own care when living with chronic medical and behavioral health conditions: scheduling visits on a timely basis, seeing the right type of provider for their needs who also happens to be in-network, and being able to afford care all present challenges.

Such coordinating services are often referred to, somewhat interchangeably, as “care coordination,” “care management,” and “case management.” These services are provided by a variety of provider types and at different levels. This Brief will only discuss them in the Medicaid context, though versions of care management exist in Medicare and the commercial market, too. In theory, deploying care managers and coordinators who have expertise in navigating complex care should reduce costs and improve outcomes. This logic has led to the proliferation of a care management cottage industry with multiple layers. Its complexity creates opportunities for overlapping responsibilities and diffuse accountability for outcomes, system inefficiencies, and increased costs with currently limited research demonstrating benefit.

These models, which often involve managed care plans’ own care management functions, have evolved beyond the scope of just clinical care to include care managers with expertise in non-clinical social services, including housing, employment, and entitlements, to more comprehensively address members’ healthcare and other needs.

For example, hospitals employ “case managers” to assist with planning patient discharges; mental health providers employ “care managers,” while homeless shelters provide “case management.” Managed care companies employ “care managers,” who are typically accessed through “800” numbers, and, in circumstances such as during or immediately after a hospitalization, may provide more intensive support. Their services are fairly formulaic and determined by algorithms refined to manage common chronic conditions. Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs) employ case managers for targeted case management. The list goes on. It is important to note that these services do not wholly overlap or occur simultaneously; most are time-limited, setting-dependent, or prompted by the presence of certain conditions or high utilization patterns.

Still, any one individual may have several such “managers” involved in coordinating their care over even brief periods of time. This raises confusion and a variety of questions. Is there enough clarity about roles and responsibilities among these different layers of care management and coordination? Is it clear what type of care management is necessary and appropriate for particular individuals? Does an algorithmic approach to standardize care planning make sense? Are care managers adequately sharing relevant clinical information and coordinating between programs to promote continuity of care?[1] Who ought to coordinate all of the coordinators?

Because managed care plans receive a capitated amount for these services, providing them should be financially accretive (in addition to being health-promoting). These programs demonstrate negligible savings (except in the very long term) however, because care management for those who have been disengaged necessarily involves re-engagement in services, which generates costs. In a system that often prioritizes financial savings over actual improvement of health, the lack of demonstrable financial savings, plus a series of cuts to the Health Home program, creates a disincentive to invest in the services. Some evaluations demonstrate decreased hospitalization but increased medication and outpatient utilization—which would be logical, given the model’s aim of engagement in low-acuity care—but point out the challenges of making conclusions given the heterogeneity of quality and capacity across the care management agencies.

In recent years, stakeholders have questioned how best to resolve the gaps within the current organizational approach to care management developed as part of the “Care Management for All” goal included in the Medicaid Redesign Team’s 2011 recommendations. Certain reforms are already in process, but some of the high-profile incidents of individuals in mental health crisis, for example, on the New York City subway, should renew urgent attention on this topic. These incidents reflect a combination of gaps in actual resources and weaknesses in care management approaches, which together leave some individuals to “fall through the cracks.”

Understanding these issues requires an in-depth appreciation of both the history and the status quo of care management structures serving individuals with behavioral health conditions in New York. This paper describes the history of different types of care management entities and programs and makes observations about the advantages and disadvantages of particular models, with recommendations for modifying current approaches.

Relevant Legacy Programs

In 1988, decades following the initial period of deinstitutionalization from long-term psychiatric institutionalization, New York State introduced intensive case management to support individuals with mental illness. The model grew to become “OMH targeted case management” (TCM), which included three levels of care management,[2] all regulated and reimbursed by OMH:

Supportive case management involved a caseload of approximately 20:1 and included screening, assessment, care planning, and service arrangement, provided by a paraprofessional case manager.

Intensive case management involved a smaller caseload of 12:1, with mental health professionals providing crisis management, screening, assessment, care planning, and service arrangement.

Blended case management involved a team approach that combined the caseloads of multiple intensive and supportive case managers.

These versions of case management were only available to individuals with mental illness and were oriented toward their mental health needs, but they also included coordination of other medical and social services.

Today, OMH describes “intensive care management” as including newer models like Health Home Plus (described later), and services like Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) and, more recently, Critical Time Intervention (CTI), which is time-limited and intended to mitigate risks of homelessness for individuals with serious mental illness. Recognizing the range of programs included under and accepted definitions for terms like “intensive care management” is essential to understanding the complexity of the issues. Furthermore, individuals enrolled in any of these programs may not be aware of the distinctions between them, given overlapping terminology and definitions.

While New York phased in its Health Home model, described in the next section, it phased out four Medicaid programs that existed at that time and which focused on members with special healthcare needs, as described below:

Targeted Case Management (TCM), was administered through OMH to address the needs of adults with serious mental illness and youth with severe emotional disorders, as described above. Providers received monthly per-member fees through Medicaid. Individuals were referred by the local public mental health authority (i.e., the local government unit, or LGU). OMH TCM began transitioning to the Health Home program in 2012 and was effectively operational until 2015.[3]

Managed Addiction Treatment Services (MATS) was an OASAS (then the Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services, now the Office for Addiction Services and Supports) program that included intensive case management and recovery support services for individuals with intensive, high-cost service needs and substance use disorders. Its guidance was mostly analogous to that provided for TCM (for individuals with mental illness). The program targeted Medicaid members with SUD treatment expenditures between $10,000 and $15,000 per year.[4] MATS was phased out by 2016.[5]

Comprehensive Medicaid Case Management Program (COBRA case management or HIV/AIDs targeted case management) was a family-centered intensive care management program for HIV-positive individuals and their families, run through the AIDS Institute at DOH. There were 46 providers statewide, 34 of which were in NYC.[6]

The Chronic Illness Demonstration Project (CIDP) was an initiative developed by the NYS Department of Health (DOH), in consultation with OASAS and OMH, which provided funding to six teams across the state to test innovative solutions that address unmet needs among high-risk individuals.[7],[8] CIDP was the most direct pre-cursor to the Health Home model, introduced below; it was operational from 2009 to 2012.

The Health Home Model

Health Home: Background

The Health Home (HH) model was established under the Affordable Care Act in 2010, to offer an integrated approach to comprehensive health care, including physical health, behavioral health, and social services for Medicaid beneficiaries with complex health needs.

In April 2011, as part of the FY 12 budget and in accordance with the Medicaid Redesign Team initiative, New York became the third state in the country to transition to the Health Home model, after Missouri and Massachusetts. Although DOH did not have experience with regulating and overseeing care management, the ACA created strong financial incentives to establish Health Homes within DOH, because the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP)[9] was 90/10 for the first eight quarters after the effective date of the creation of Health Homes (i.e., the authorization of the State Plan Amendment (SPA)). In most circumstances, FMAP is 50/50, so the Health Home ratio of 90/10 was quite advantageous to the State.

Health Home: Core Services

Health homes are required to provide six core services in accordance with the State Plan Amendment:

Comprehensive Care Management

Care Coordination and Health Promotion

Comprehensive Transitional Care

Enrollee and Family Support

Referral to Community and Social Supports

Use of Health Information Technology (HIT) to Link Services

There is no federal Health Home standard for maximum caseloads and New York has not named its own standard maximum caseload for the regular Health Home model, although other special populations Health Home models (including Health Home Plus, described below) do have caseload specifications.

Each Health Home enrolled member is assigned a care manager, who is employed by the care management agency, develops a comprehensive care plan, integrating primary care, behavioral health, and social services (like housing support), and helps the member with transportation to visits and achieving health goals. Members can also get help with signing up for SSI, SNAP, long-term disability, and any other programs to which they are entitled.[10]

Health Home: Structure

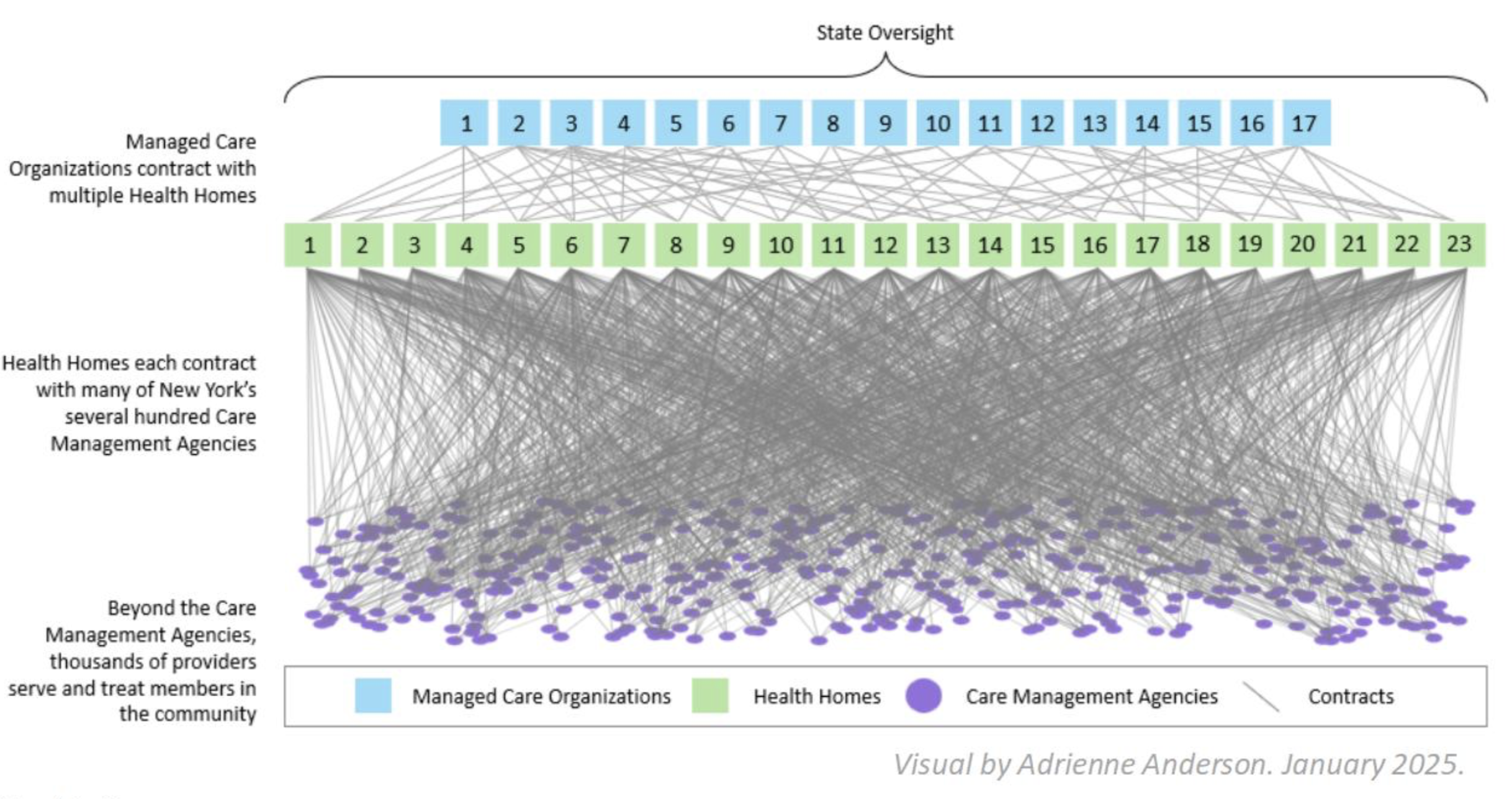

The graphic below illustrates the complexity of the Health Home structure. The Health Home program is composed of many layers, with State (i.e., NYS DOH and OMH) oversight at the top. The State’s 17 managed care organizations contract with the 23 Health Homes,[11] and the Health Homes contract with the hundreds of Care Management Agencies in New York State. Beyond the figure, there are the thousands of community-based service providers and the members themselves.

Health Homes

In New York, the Health Home program operates as an integrated network through Health Home “lead” entities and care management agencies (CMAs). Health home leads, often referred to just as “Health Homes,” are administrative organizations, including hospitals, home health agencies, and behavioral health providers, that contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) to manage services in a given region.

Health home leads are responsible for the infrastructure of the Health Home model, for example, providing data management, billing and reimbursement processing, and quality and regulatory compliance monitoring. This consolidated administrative effort enables operational economies of scale for the Health Home model, which would be more limited if it only worked through the in-house capacity of local providers. Strong Health Home leads may opt to deliver additional value beyond typical “MSO” (management services organization) functions, by, for example, facilitating learning collaboratives and offering training to their partner CMAs.

New York has established a network of 23 designated Health Homes: 10 serve both adults and children; 2 are designated to serve children only; and, 11 are designated to serve adults only.[12] These 23 Health Homes contract with hundreds of CMAs statewide.

Managed Care Organizations

Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) are charged with monitoring the quality and efficiency of the care management services provided by Health Homes, ensuring that they align with Medicaid guidelines and the State’s care management objectives. In addition, MCOs provide data and oversight that help Health Home leads and CMAs manage member needs effectively.

MCOs may identify eligible Medicaid members for Health Home enrollment and facilitate their assignment to an appropriate Health Home lead, though there are other methods for identifying potential Health Home members, as described in Eligibility and Scale. Once a member is enrolled, the MCO reimburses the Health Home lead for care management services through a per-member per-month (PMPM) payment structure.

Care Management Agencies

Health Home leads contract with care management agencies, which are community-based organizations including patient-centered medical homes, housing agencies, and behavioral health providers. CMAs typically lack the infrastructure or capacity necessary to operationalize the Health Home care management model, so contractual relationships with Health Home leads create the overall effect of the “Health Home” in their respective geographic areas. The Health Home lead may assign its members to CMAs, or CMAs may identify potential members directly. This is discussed further in Eligibility and Scale.

The actual provision of health or social services may be carried out by other providers, with the CMA monitoring members’ engagement, or by providers that are a part of the CMA’s underlying community-based organization (CBO).[13] Importantly, CMAs are not exclusive to a single Health Home lead; many CMAs work with multiple leads, and vice versa.

CMAs provide care coordination and management services intended to help members access comprehensive, continuous care across different settings. This involves working directly with members to address their health and social needs, coordinating visits with healthcare providers, supporting medication adherence, and connecting members with community resources such as housing support and food assistance. CMAs often serve as a central point of contact for members, ensuring that care plans are followed, identifying and resolving gaps in services, and liaising between providers and members. In practice, quality varies, and the most effective CMAs do all of this and more, while others are resource-constrained and only offer the bare minimum of, essentially, case management.

Health Home: Payment

NYS reimburses Health Homes with a per-member per-month care management fee at two levels, which depend on case-mix and geography (i.e., Downstate or Upstate). The State has provided guidance that no more than 6% of the Health Home payment should be retained for administrative purposes: 3% for Managed Care Plans and 3% for the Health Home lead.

Health Homes bill MCOs, which receive the PMPM payments from the State. CMAs submit claims for care management services to their respective Health Homes, which the Health Homes review and reimburse, as appropriate.

Health Home: Eligibility and Scale

Since the HH program focuses on serving Medicaid beneficiaries with complex needs, screening individuals for eligibility is critical, and happens in a few ways. Providers “on the ground” can flag Medicaid member patients and refer them to a Health Home for formal assessment, at which point they can enroll, if eligibility is confirmed. This is considered “bottom-up” identification.

Alternatively, the State or an MCO can use claims data to flag eligible Medicaid members and assign them to appropriate Health Homes (based on their location, existing relationship to care, etc.), which then must connect with the flagged individuals to complete eligibility screening and enrollment. This is considered “top-down” identification.

To qualify for Health Home services in New York State Medicaid, individuals must have either two chronic conditions from a defined list or one single qualifying condition (i.e., either HIV/AIDS, Serious Mental Illness, Sickle Cell Disease, Serious Emotional Disturbance, or Complex Trauma), with verification of conditions required for enrollment and ongoing eligibility. In New York, individuals with a history of high emergency room utilization or frequent hospitalizations are also prioritized.

HH referrals come from Local Government Units (LGU), Single Point of Access (SPOA), Local Departments of Social Services (LDSS), the Human Resources Administration (HRA), the HIV/AIDS Service Administration (HASA), healthcare facilities, and other providers.[14]

The State initially estimated that 975,000 individuals would meet the criteria for the Health Home program, out of the Medicaid population of then approximately 5 million.[15] At the time of the SPA, the state prioritized enrolling 500,000based on their need, with additional priority for those with mental illness or substance use disorders. However, of the approximately 7 million New Yorkers enrolled in Medicaid today, approximately 180,000 are currently enrolled in Health Homes.[16]

This lower-than-expected consistent enrollment volume reflects several challenges, including the opt-in, voluntary nature of the program and the impact of State budget actions that reduced activities to identify and enroll HH-eligible members, effectively limiting its scale. Additionally, the difficulty of engaging high-need populations, workforce shortages, extensive documentation and reporting, and reimbursement changes, have all strained under-resourced CMAs. Some community-based organizations that served as CMAs lost enough money providing care management services that they shuttered their

CMA line of business. Such market exits reduced the overall program’s capacity, since CMAs play a critical role in outreach to potential Health Home members.

Recent Proposals to Reform the Health Home Program

During MRT II, the State noted several proposals to drive efficiencies in care management services, specifically within Health Homes, including:[17]

– Eliminate outreach payments

[The State began winding down Health Home billing for outreach services in 2017. This was completed in 2020. This is an example of a budget action that limited support for activities used to identify HH-eligible individuals.]

– Move low acuity members into less intensive case management

[The State issued guidance to this end in September 2020.]

– Increase accountability by penalizing Health Homes that do not meet quality standards

[The State implemented a new Redesignation Policy for all Health Homes, which introduced an audit process and a pathway for closing low-performing Health Homes.]

– Achieve administrative efficiencies by reducing unnecessary documentation

– Consolidate and geographically optimize Health Home networks”

It is not clear how much progress has been made in implementing the final two of these MRT II proposals. There is still considerable variation in the concentration of Health Homes by county, as shown in the map below.

An interactive version of this map, which displays the names of Health Homes Serving Adults, Health Homes Serving Children, and MCOs for each NYS county, is available on the Step Two Policy Project website’s Resources page.

Health Home Plus

New York’s Health Home Plus (HH+) program represents an intentional continuation of intensive and supportive case management models described above (on p. 3). OMH had a desire to preserve the availability of specialized care management services for individuals with serious mental illness, which would go beyond the scope of the traditional HH model. HH+, then, is an enhanced version of the Health Home program, focused on Medicaid recipients already enrolled in Health Homes who have serious mental illness and need more frequent and sustained engagement to stabilize their conditions. This includes individuals with conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe depression; HH+ target individuals have needs that are complex, acute, or both. The monthly capitation rate is higher than that of the traditional HH program, to reflect these additional needs.

Health Home Plus: Structure

HH+ care managers work with MCOs and providers to ensure smooth service delivery and effective communication. This coordination includes sharing relevant data and monitoring quality metrics to promote continuity of care, improve outcomes, and reduce hospitalizations and emergency visits.

HH+ care managers receive regular, often weekly, supervision from experienced clinical supervisors. The latest New York State guidance mandates that HH+ care managers have caseloads of one (1) full-time employee to a maximum of 20 Health Home Plus recipients. HH+ programs in New York are required to provide four “core” services per month, two of which must be face-to-face, and at least one of those face-to-face contacts must be with the care manager or coordinator.

This reflects a higher standard for engaging and monitoring individuals with complex behavioral health needs as compared to the traditional Health Home model. This more prescriptive model, the limitations on blended caseloads,[18]and the requirements for more experienced care managers all likely play a role in limiting the scale of the HH+ program.

Health Home Plus: Eligibility and Scale

In 2014, OMH and DOH first implemented Health Home Plus (HH+), targeting Assertive Outpatient Treatment (AOT) participants who were also enrolled in a traditional Health Home. HH+ expanded to include individuals discharged from State Psychiatric Centers (i.e., State-funded and run inpatient mental health facilities) and corrections-based mental health units at Central New York Psychiatric Center, which is a forensic facility. Eligibility was further expanded in May 2018 to include a number of other populations, including individuals stepping down from Assertive Community Treatment (ACT); those meeting certain definitions for homelessness; those with high inpatient and ED utilization; [19] those with criminal justice involvement, those ineffectively engaged in care;[20] and others[21] subject to the discretion of the local Single Point of Access (SPOA)[22] and/or the appropriate MCO. DOH has also expanded the eligible HH+ target population to include individuals who are HIV-positive and virally unsuppressed.

Referrals to HH+ care management come from behavioral health providers, MCOs, hospitals, and other healthcare providers. The referrer provides documentation verifying that the individual meets the requirements for Health Home Plus services based on previous utilization patterns. Once a referral is received, the Health Home must ensure the individual is promptly assigned to a CMA formally designated by OMH as a “Specialty Mental Health Care Management Agency.”[23] Members are notified by mail and can opt out, returning to their original mainstream plan.

OMH has indicated an intention to increase HH+ capacity,[24] including by issuing an RFP to award up to 63 specialty CMAs up to $2.5 million (total) for providing HH+ services to individuals “experiencing a critical transition in care,”[25] and encouraging hospitals to refer appropriate patients to intensive care management, including HH+, prior to discharge.[26]

Health and Recovery Plans

Health and Recovery Plans: Background

In 2014, the State introduced the Health and Recovery Plan (HARP) initiative as it transitioned behavioral health from fee-for-service to Medicaid managed care and sought to address the needs of individuals with co-occurring serious mental illness (SMI) and substance use disorder (SUD), in particular. HARPs are specialized managed care plans that provide medical, mental health, and substance use services in an integrated model for high-need Medicaid enrollees 21 and older with a chronic mental illness or substance use disorder. This formal integration is intended to reduce the effects of the siloes that fragment care delivery for most individuals with complex, co-occurring needs.

Unlike HH and HH+, which are care management programs that complement managed care plans, HARP is a discrete type of managed care plan, administered by (a subset of) the same MCOs that manage mainstream Medicaid managed care plans. Accordingly, HARP members are automatically qualified for Health Home enrollment and can still enroll in HH and HH+ for care management.

Health and Recovery Plans: Services

Every HARP member has access to a designated care manager, whether through their HARP (i.e., MCO care management) or through a Health Home, who assists the HARP member in developing a person-centered care plan that integrates their physical and behavioral health services.

One of the HARP model’s benefits is Behavioral Health Home- and Community-Based Services, or “BH HCBS,” which provide tailored support with job training, employment, and housing assistance, among other services. There are further risk-based criteria for eligibility for BH HCBS[27] and Community Oriented Recovery and Empowerment (CORE) that take members’ utilization of emergency department and other hospital services, as well as homelessness and past justice system involvement, into account.[28]

HARP members interested in BH HCBS are individually assessed for eligibility, either by a care manager at a CMA, which requires the member’s enrollment in a Health Home, or, for those not enrolled in a Health Home, by a coordinator employed by a Recovery Coordination Agency contracted with their HARP.

An example of the HARP member journey is illustrated below, from the Final Report on Managed Care Organization Services (p. 63) :

Health and Recovery Plans: Payment

Health and Recovery Plans use a capitated payment method, where MCOs receive a fixed monthly payment for each enrolled member. HARP plans receive significantly higher capitation rates[29] than mainstream managed care and carry a minimum medical loss ratio (MLR) of 89%, rather than 86%, for other Medicaid lines of business.[30] This combination of high premiums and narrow MLR has generated some interest in how remittances are ultimately reinvested, and for whose benefit.[31],[32]

Health and Recovery Plans: Eligibility and Scale

There are currently 12 HARP plans statewide. HARP eligibility, as of July 2023, numbered at 198,403 individuals statewide, with 171,665 enrolled.[33] In contrast, current Health Home enrollment of 180,000 is likely much lower than the Health Home eligible population. Although HARP members are automatically eligible for Health Home enrollment, only 21% of HARP members are enrolled in a Health Home.[34]

The HARP approach of “top-down” claims-based eligibility is limiting, both because of lagged claims and the absence of relevant claims for individuals recently incarcerated or admitted to an OMH psychiatric center, or for individuals with no documented history of behavioral health symptoms or diagnoses. This is something the HH model ultimately addressed by permitting “bottom-up” identification of potentially eligible HH members by providers and MCOs.

Per OMH,[35] HARP-eligible members of MCOs that offer a HARP product are notified by the State of their option to enroll in the HARP and can opt out or choose to enroll in another HARP within 30 days. HARP-eligible members of MCOs that do not offer a HARP product receive instructions on how to enroll in a HARP. Once an individual is enrolled in HARP, they have 90 days to change HARPs or return to mainstream, otherwise they are locked into HARP for nine months (i.e., until they reach a full calendar year of enrollment).

Health and Recovery Plans: Outcomes

While the theory behind integrated HARP plans makes sense for a population that faces many barriers to high-quality, coordinated care, evaluations of the program have observed mixed results.

There has been lower-than-expected uptake in BH-HCBS (only 3% of HARP members utilized HCBS or CORE Services in the last year),[36] among other services.[37] Although Health Homes (and CMAs, in particular) are not the exclusive means to BH HCBS access that they once were,[38] the financial incentives underlying Health Homes are not compatible with enrolling HARP members, who may be relatively difficult to engage and have more complex needs. The higher rate available through the Health Home Plus model mitigates the Health Homes’ disincentive against enrolling HARP members somewhat, but the issue of low BH HCBS and CORE participation persists.

Based on data from 2013-2019, HARP members who maintained at least two years of continuous enrollment in HARP experienced significant reductions in hospitalizations and increased access to and utilization of outpatient services.[39]This finding suggests that the original logic of the model holds: high-touch, integrated approaches help people access low-acuity care and, ideally, keep them out of the hospital better than other models do.

However, other evidence, including in the Final Report on Managed Care Organization Services (p. 11), suggests a more limited impact on outcomes:

Between 2015/2016 and 2020, HARPs demonstrated no change in performance on key measures such as seven- and 30-day follow-up after a hospitalization or ED visit and potentially preventable readmissions for mental health.

The same report offered some observations as to how New York’s model differs from other states’ models and may be getting in the way of its own success, including by not restricting the number of MCOs allowed to offer HARP plans, and by having overlapping functions among MCOs, Health Homes, and CMAs, which can be confusing for members.[40]

Care Management in Mainstream Managed Care

As part of the original Medicaid Redesign Team efforts in 2011/12, the State established the initiative of “Care Management for All,” designed to affirm the goal of providing care management to all Medicaid enrollees by 2019.[41]Unfortunately, there are limited data to understand the achievement of that goal to date, but since the Health Home program, HH+, HARP, and HIV SNPs[42] emerged in the interceding years, the reach of care management has certainly widened.

It is important to note that mainstream managed care, which provides comprehensive medical services including hospital care, physician services, dental services, pharmacy benefits, and more, also offers care management, typically telephonically. However, mainstream plans are not designed to serve individuals with behavioral health needs, who are the focus of this paper. People with well-managed behavioral health conditions who are medically stable and do not have other unmet health-related social needs may be suitable for mainstream plans, and likely would not meet eligibility criteria for HARP or even a Health Home. Along the continuum of most-involved care management arrangements, mainstream managed care plans offer more care management services than their predecessor fee-for-service plans could or would (because they actually receive capitated payment for performing these services) but less than integrated plans like HARP or targeted programs like HH+ do.

Accountability for Key Players in Care Management

The issue of accountability for quality and outcomes is essential to both formal evaluations of care management (and behavioral health service delivery) model fidelity and efficacy, and to those responsible for operational efficiency and ensuring value-add of these programs.

As outlined earlier in this paper, the logic of structured care management makes good sense: providing expert, individualized support for people with multiple health challenges and health-related social needs should help them get and stay engaged in care and improve their health. Short-term improvements in health should result in reduced utilization of costly hospital visits and admissions and should evolve into longer-term stability, too.

Anecdotally, the quality of programs can vary widely within a given region, from year to year, due to fluctuating staffing availability, experience, and expertise, financial instability of provider agencies, changing population demographics, and MCO enrollment churn. And because these models are administratively complex, there may be aspects within a single program that function well while others are weak links.

In the Health Home model, for example, leads are responsible for quality assurance. Health home leads have different methods for evaluating and holding their CMAs accountable, such as tiering their CMAs by performance and even eliminating underperforming ones during re-contracting periods. MCOs also can transfer their member to a different Health Home if the member’s current Health Home is underperforming.[43] These each represent levers for controlling the quality of overall Health Home performance, though ostensibly, there is still room for improvement in overall accountability among HHs, CMAs, and MCOs, both within and beyond the HH context.

Before introducing any new care management models or variations on existing ones, we must better understand which are most effective, scale those up, and phase out others. Performance against established measures is not publicly disclosed, so it is impossible for outside observers to judge how effective the programs are.

The State monitors the quality of various care management programs through regular reporting. DOH audits Health Homes for quality and compliance and shares the information back to the providers. Health Homes are required to adhere to specific reporting and quality accountability standards detailed in the “Health Home Measure Specification and Reporting Manual,” which outlines the performance measures, data submission guidelines, and evaluation criteria that Health Homes must follow. There is a performance improvement process involving technical assistance, which includes the potential for de-designation by the State.

Performance data for HARP plans and HIV SNPs are reported discretely to the Quality Assurance Reporting Requirements (QARR), as they are their own plan types,[44] unlike HH/HH+ programs, whose data are captured via the Health Home Care Management Assessment Reporting Tool (HH-CMART). The QARR measures performance across multiple domains, such as access, care management effectiveness, and health outcomes, ensuring alignment with state and federal quality goals.[45]

Roles of NYS Agencies

The New York State Department of Health designed the operational aspects of the care management models described earlier and monitors their regulatory compliance at the State and federal levels. As described just above, it also monitors performance and ensures accountability through regular reporting of quality and costs, with incentives tied to quality under certain value-based payment models (e.g., in the HARP value-based payment (VBP) arrangement).[46] Over the years, various models were proposed to transfer practical operational control of these programs to the New York State Office of Mental Health. Although these proposals would not have altered DOH’s primacy in relation to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), they were not adopted.

The New York State Office of Mental Health has subject matter expertise in the care of people with serious mental illness and has led the clinical aspects of design and programmatic guidance for models like HARP and HH+, which are intended for that population. OMH also designates select CMAs as Specialty CMAs, which are able to work with individuals enrolled in HH+.[47]

The role of the State changed significantly during the transition from targeted case management to the Health Home model. Under TCM, OMH contracted directly with care management providers. Under the Health Home model, the State only contracts directly with MCOs, not with Health Homes or CMAs. While Health Homes have a redesignation process with the State and can decide which CMAs to work with, there is some distance between the State and the CMAs with respect to oversight and accountability.

Challenges with Current Models

Quantifying Engagement

Much of the formal evaluation of various care management models has explored whether they achieve their stated goals of achieving one or more aspects of (variations on) the quadruple aim: enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing costs, and improving staff satisfaction or provider experience. Research has monitored changes in the utilization of primary care and behavioral health outpatient services, rates of hospitalization and rehospitalization, use of emergency services, as well as medication utilization for individuals enrolled in these programs.

The topic of engagement in the treatment of mental illness is a hotly contested one in academic psychiatry and health services research—not nearly as straightforward as it may seem. Researchers have concerns about qualitatively defining engagement to capture the variety often seen along the behavioral health continuum, and about how to quantify engagement in terms of the number and length of visits.

For example, medication fill rates (i.e., the rate at which prescriptions are picked up compared to the rate at which they are prescribed) may seem like an effective proxy for adherence with a medication treatment regimen, but there are many factors mediating whether an individual will pick up a prescription. Some of these factors are exactly where the role of care management ought to come in, such as coordinating transportation to the pharmacy, or correcting contact information so that reminders of a “ready” prescription actually reach the patient.

Notwithstanding the difficulty of measuring engagement, we should not let the perfect be the enemy of the good: “[f]indings suggest that Health Home enrollment may facilitate engagement in behavioral health care. […] Reductions in inpatient utilization after Health Home enrollment suggest that, for individuals receiving mental health treatment, Health Homes may be an effective intervention.”[48]

These and similar findings reiterate that there is value of care management in keeping members out of the hospital and involved in care, but questions remain as to whether the paradigm of an (arbitrary) number of in-person contacts with a member each month, for example, is the right approach. Ideally, the behavioral health data environment will evolve to better support outcomes-focused and more timely performance measurement, which in turn, can facilitate more value-based payment and innovation.

Plan Oversaturation

New York also has many mainstream Medicaid managed care plans (17 statewide,[49] 12 are available within New York City, and 12 have HARP products), which introduces the opportunity for members’ mobility between plans from year to year and necessitates that membership is spread thinly across the plans. This churn and relatively low member volume create a disincentive for plans to innovate and improve, since savings are unlikely to be captured internally or quickly. While some choice is worth preserving, arguably members currently have too many options that do not meaningfully differ. Interestingly, in targeted models like the HIV SNP, which have far fewer participating plans, the plans see comparatively lower annual turnover than traditional plans (i.e., 11% at Amida Care vs. 25%, the national average).[50]

Step Two has written in several of our pieces about New York State’s reluctance to create “winners” and “losers,” as illustrated by the current controversy involving the consolidation of fiscal intermediaries in CDPAP. This aversion comes to the surface anytime a policy solution potentially eliminates some of the relevant, existing players, whether they be fiscal intermediaries, managed long-term care plans, or, in this case, MCOs (and Health Homes).

Administrative Complexity and Program Redundancy

Given the administrative expense associated with the maintenance of so many distinct plans, and the current level of enrollment in Health Homes, does it make sense that the State has so many Health Homes? Would a flatter organizational structure (i.e., between the MCOs, HH leads, and CMAs) work more effectively and generate efficiencies?

More fundamentally, there is rampant redundancy from the overlapping functions of and populations served by the various programs introduced in this paper. While all HARP members have access to care management, many do so through their MCOs directly, 21% do so through a Health Home, and a subset of them do so specifically through HH+. People with HIV may be served in mainstream managed care and Health Home Plus, or through an integrated HIV SNP. Perhaps maintaining these options has value, but the rationale for choosing any one of them ought to be clearer and more standardized.

Without sufficiently distinct program purposes and target populations, members may not enroll in the right care management programs for their needs, and the incentives of these different programs mean it does not always make sense to expend equal energy on all members. These programs should be reformed to better allocate resources and expertise to the more cost-effective and clinically valuable programs— as indicated by improved outcomes.

Potential Solutions

Alternative Model: North Carolina

North Carolina shuttered its care management systems 15 years ago. Two years ago, the state’s managed care redesign reintroduced a Health Home model as part of the package, and last year the Health Home project officially launched as “Tailored Care Management.” The State’s Medicaid program, which only transitioned to managed care in 2021, now features three types of integrated managed care products, including specialty plans called “tailored” plans, for populations with serious mental illness, substance use disorders, traumatic brain injury, and intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD).[51],[52]

Individuals are automatically reviewed for eligibility for a tailored plan in North Carolina upon application to North Carolina Medicaid. Managed care companies, which operate regionally with one standard and one tailored plan per geographic region, also function as the Health Homes. These companies provide data and infrastructure, including claims and physical health data, to care management agencies. Where CMAs are not present, MCOs provide care managers to support individuals who might otherwise fall through the cracks. The MCOs also liaise with the state and manage comprehensive data across services.

Tailored Care Management, which is the Health Home benefit itself, is available through both the tailored plans, described above, and through prepaid inpatient health plans (PIHP) for individuals in the State’s “Medicaid Direct” program, which is analogous to mainstream managed care plans in New York.

According to the SPA:

“Health Home members will be assigned to one of three approaches for obtaining Tailored Care Management: a primary care practice certified by the state as an Advanced Medical Home Plus (AMH+) practice, a behavioral health or I/DD provider certified by the state as a Care Management Agency (CMA), or a plan-based care manager. Members will have the ability to exercise choice in their assignment and change that assignment. To become an AMH+ practice or CMA, organizations must go through a state-designed certification process.

“The organization that an individual is assigned to will assign a care manager who will work with a multidisciplinary care team in delivering Tailored Care Management, inclusive of the six core Health Home services.

“Each Health Home member will be assigned to an “acuity tier” based on known health conditions and experience. The acuity tier determines an expected service intensity and monthly case rate for each member, with providers being paid more for high-acuity members and vice versa. Payments are retrospective and a provider must demonstrate that it has delivered at least one Health Home core service in the previous month in order to access the payment.” [53]

In contrast to North Carolina’s transformation model described above, New York’s Health Home model involves the intermediary of the managed care company by default: there is the role of the State, the Health Home lead (e.g., CBC, Hudson Valley Care Coordination), the care management agencies, plus the managed care company. Role confusion abounds. CMAs are often confused about where to find relevant data because of this bidirectional relationship. Individuals move between CMAs, so CMAs also need to track that activity.

If North Carolina’s “tailored care management,” when delivered through mainstream managed care, is analogous to Health Home care management in New York, its “tailored plans” are analogous to our SNP plans. These are discrete integrated plans that exclusively serve high-need populations and provide care management, in contrast to traditional managed care plans, where the care management function, provided through Health Homes, is distinct from the MCO. Integrated models combine the provider and the payer and include a care coordination/management function, as this Brief will explore next.

Proposed Integrated Plan Model

In the most recent round of proposals for consideration for the latest 1115 waiver, the New York City Health + Hospitals Corporation proposed a “special populations model” – an integrated, full-capitation risk model designed to manage the care of the target population and provide services. The target populations included the chronically homeless and the reentry population (i.e., those being released from prisons and jails). Very little is publicly available about this proposed model, besides the fact that the model was rejected by CMS, and the following, excerpted from the Commission on Community Reinvestment and the Closure of Rikers Island Report:

“During incarceration, justice-involved persons will be linked to points of care within an Accountable Care Organization comprised of the NYC Health + Hospitals system and community partners through outreach, navigation, and care management services. Under an advanced value-based payment model funded by enhanced Medicaid funds, the provider partnership will assume new responsibility for the cost of care and provide new care management resources while maintaining patient relationships with their existing providers and health plans. The proposed partnership will therefore establish a sustainable network of accessible, accountable, high quality care for individuals who may be marginalized by current systems despite higher health care needs.”[54]

Opportunity for Expansion of Existing Integrated Plan Model: HIV Special Needs Plans

While most of New York Medicaid’s managed care offerings are nonspecific and untailored, HIV Special Needs Plans (SNPs) are available to Medicaid beneficiaries who are living with HIV/AIDS, are homeless, or are transgender. NYS Medicaid introduced the program in 2003, but enrollment grew most dramatically after 2011, when Medicaid members with HIV were required to enroll in managed care, either through an HIV SNP or a mainstream plan.[55] As of 2021, over 42% of Medicaid-eligible people living with HIV in NYC were enrolled in such a plan.[56]

Like HARP and unlike HH and HH+, HIV SNPs are discrete plans. These SNPs offer regular Medicaid benefits plus specialized HIV services and have an organizational and cultural commitment to serving the target population. In the SNP model, the primary care provider must have formal training in HIV care or be an HIV specialist. Each enrollee has an interdisciplinary care plan. HIV SNPs utilize intensive care coordination, health navigation, and outreach services to help enrollees manage multiple conditions.[57] Members may opt into additional Health Home services (specifically the HIV Health Home Plus program) and are eligible for assessment to access BH HCBS services.

Amida Care is the largest Medicaid SNP in New York City, with nearly 10,000 members. Members are each assigned an integrated care team, consisting of a:

Care Coordinator to help with appointments, coordinate with doctors, etc. … Case Manager to connect you with community resources such as: mental health and substance abuse treatment; housing and legal services; transportation assistance; health education; domestic violence services; and homeless services; [and a] Health Navigator to help you choose a doctor for your needs and link you to community agencies.

The history of the HIV SNP in NYS as being “built on the existing network of the AIDS centers, HIV primary care providers (PCPs), HIV Specialists, and HIV case managers to harness existing expertise in the HIV field”[58] in the wake of the AIDS epidemic invites comparison to the present moment in the context of our macro-level behavioral health crisis. And this expertise appears to have paid off:

Between 2008 and 2016, Amida Care estimated that their services led to a 74% reduction in hospitalizations, 34% reduction in hospital length of stay, and a 63% decline in emergency room visits, all totaling $150 million in savings to New York State Medicaid.[59]

Demand for behavioral health services has never been higher, and supply has not kept pace. Care coordination and care management, especially in a functionally integrated plan like an SNP, help ensure the availability of treatment resources by reducing operational inefficiencies and addressing barriers to access and engagement (e.g., mitigating transportation challenges) so members’ health can improve more consistently and quickly.

The SNP model has many advantages, but one of its disadvantages is a relative lack of scale. SNPs have sought to address the scale issue by expanding the scope of the targeted population. For example, the State has supported a series of eligibility expansions to include HIV-negative members within transgender and homeless populations – both of which are at high risk of HIV infection.

Imagining a more comprehensive behavioral health special needs plan in New York, one could imagine expanding HARP eligibility to include individuals who are simply at high risk of becoming eligible for HARP, such as individuals experiencing homelessness. These individuals might benefit from the specialized networks and expertise of HARP plans in addressing substance use disorders and mental illness but, under current eligibility criteria, may be overlooked if they have not yet demonstrated the utilization patterns or clinical complexity to warrant more attention.

Proposal

This Brief has described a fragmented and overly complex system of care management for individuals with behavioral health needs in New York State’s Medicaid system. Various care management programs that focus on similar populations have different eligibility criteria, goals, reporting conventions, administrative structures, and oversight. Their overlapping functions and target populations and lack of integration often result in confusion for providers and members alike. Variation in operational rules —exacerbated by varying quality and capacity among key players—undermines consistency in outcomes and savings. These weaknesses indicate a need for a more streamlined and accountable approach.

To address these issues, New York should consolidate and simplify the care management landscape by:

1. Redefining Care Management Layers

Existing models, especially the Health Home model, should be reorganized to reduce redundancy and improve clarity. HH and HH+ should focus on their core strengths—coordinating care for mainstream managed care members with complex needs, leaving integrated care management for individuals with behavioral health needs to HARPs and HIV SNPs.

HARPs should ultimately be transformed into behavioral health special needs plans that fully include behavioral health, physical health, and social services, much like HIV SNPs do.[60] This approach would ensure that individuals with behavioral health needs receive tailored, coordinated care without the confusion of multiple overlapping programs and with the attention, efficiency, and expertise an integrated, population-focused plan provides best.

Although this Brief is limited to discussing care management approaches for individuals with behavioral health needs, it is worth noting that existing Health Home infrastructure may work well serving individuals with other types of chronic conditions. Health Homes could continue to provide administrative functions, like billing, assigning members to CMAs, and monitoring performance but ideally with more flexibility, not prescribed by required monthly contacts or other arbitrary standards of engagement.

2. Procuring Managed Care Organizations

The Hochul administration unsuccessfully advanced a proposal calling for a formal, competitive procurement of Medicaid managed care plans in both the FY 23 and FY 24 Executive Budgets. Procurement would help ensure the structure and quality of all participating plans meets State-established standards, consolidate the delivery of managed care through plans with more concentrated expertise and resources, and, as found in the Final Report on Managed Care Organization Services (p. 85), deliver substantial savings to the State.

Additionally, procurement would provide an opportunity to formally designate some smaller number of plans (with evidence of appropriate expertise and resources) as behavioral health special needs plans, separate from traditional mainstream plans.

Despite strong political opposition from the legislature and Medicaid managed care plans, the procurement strategy makes programmatic sense, and hopefully, it may become politically viable.

3. Enhancing Accountability and Quality

Accountability must be strengthened across all levels of care management. The State should take a more active role in monitoring quality, despite the political resistance to challenging providers in the NY environment.

Standardized metrics—about hospitalization, follow-up outpatient care, and medication adherence—for Health Home leads, CMAs, and MCOs (in their HH/HH+ capacity and in the context of HARP) should be regularly publicly reported, actively guide program evaluation, and inform operational and contracting decisions.

Additionally, clear, transparent, and real-time performance data must be made publicly accessible and scored by either the State or an impartial third party. This approach will enable the identification and removal of underperforming entities, including CMAs, Health Home leads, and plans, fostering a higher standard of care across the system.

4. Integrating Technology and Data Sharing

The fragmented nature of the current system underscores the urgent need for a more robust data-sharing infrastructure to enhance communication among providers caring for the same individual. While New York has made significant investments in health information technology, such as the Statewide Health Information Network for New York (SHIN-NY), leveraging this infrastructure effectively will require more coordinated planning.

Currently, the fragmentation in the system is mirrored in the data infrastructure, as siloed reporting mechanisms and inconsistent definitions and standards make it difficult to adopt a unified approach. Improving data integration by standardizing definitions and measures and investing in interoperability and even centralized solutions, would streamline reporting and make using the data at the point of care more intuitive.

Behavioral health providers were excluded from original “meaningful use” initiatives, leaving a critical weakness in the sector’s data foundation. Providers expend significant effort and devote scarce staff resources to regular reporting but may only receive feedback with a corrective directive or in aggregate (i.e., not provider-specific), which limits its utility for clinical purposes. These data issues reflect the origins of EMR and reporting in billing-oriented data collection and organization, rather than patient-centered approaches. Establishing more bilateral expectations around data sharing between providers and various reporting authorities would go a long way to ensuring that data reporting efforts produce clinically relevant and actionable information.

5. Simplifying Enrollment and Eligibility Processes

Enrollment in care management programs should be streamlined to reduce administrative burdens and increase access. A hybrid approach that combines claims-based identification with provider-driven referrals, as seen in North Carolina’s “Tailored Care Management” model and in New York’s HH model, provides the best chance of capturing appropriate, eligible members. Publishing documents clarifying the areas of distinction versus overlap for the existing programs would be a valuable effort by the State, both for participating providers and for potential and current members.

In conclusion, New York’s current care management system is well-intentioned but too complicated, leading to inefficiencies and inconsistent outcomes. By streamlining care management layers, procuring MCOs to ensure expertise and quality, enhancing accountability, leveraging data, simplifying enrollment, and expanding the potential of integrated specialty plans, the State can create a more cohesive and effective system that better serves Medicaid members with complex behavioral health needs.

[1] This question particularly concerns individuals who have recently been incarcerated or admitted to a State psychiatric facility, since clinical information from those settings is not readily available to providers in other settings.

[3] RAND Corporation, Independent Evaluation of the New York State Health and Recovery Plans (HARP) Program: Interim Report, November 13, 2020. p. 5.

[4] Neighbors, C., et al., Effects of a New York Medicaid Care Management Program on Substance Use Disorder Treatment Services and Medicaid Spending: Implications for Defining the Target Population, January 30, 2022.

[5] NYS DOH, Health Home TCM Legacy Rates, September 2017.

[6] United Hospital Foundation, Implementing Medicaid Health Homes in New York, 2013.

[7] New York State Health Foundation, Care Management in New York State Health Homes, August 2014.

[8] NYS DOH and the Center for Health Care Strategies, CIDP Summary Report, February 24, 2012.

[9] FMAP indicates the proportion of funding the federal government will contribute relative to a state’s obligation.

[10] Community Healthcare Network, Health Home Services.

[11] The most recently available list of contracts between MCOs and Health Homes, from 2019, reflects 293 contracts between the 23 MCOs and 37 Health Homes active at that time. At the time of this writing, there are 17 active NYS MCOs and 23 HHs, so there are fewer total contracts than in 2019 but still many.

[12] Additionally, the Care Coordination Organization/Health Home (CCO/HH) program serves approximately 120,000 individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities through 7 CCOs statewide.

[13] Any given CBO might offer multiple services, including CMA, HH, and direct service provision.

[14] NYS DOH, Health Home Provider Manual: Policy and Billing, July 2019. p. 12.

[15] Citizens Budget Commission, Options for Enhancing New York’s Health Home Initiative, May 1, 2018.

[16] It is difficult to find an exact count of Health Home enrollment, as program reporting is not publicly available. Sources alternately quote the current figure at 170,000 or 180,000. There is constant movement in and out of Health Homes so the total number of unique members who have been served over time is likely much higher.

[17] NYS DOH, New York Medicaid Redesign Team II: Meeting 2, March 10, 2020. p. 28.

[18] Ibid, Health Home Plus Program Guidance for High-Need Individuals with Serious Mental Illness Re-Issued December 2024, p. 12. “… a caseload mix of HH+ and non-HH+ is allowable if the HH+ ratio is less than or equal to 20 HH+ recipients to one (1) qualified HH CM.”

[19] NYS OMH, Health Home Plus Program Guidance for High-Need Individuals with Serious Mental Illness Re-Issued December 2024, p. 2. High utilization is defined in guidance as having one or more of the following: three or more psychiatric inpatient hospitalizations within the past year; or four or more psychiatric ED visits within the past year; or three (3) or more medical inpatient hospitalizations within the past year and who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

[20] Ibid. Ineffective engagement is defined in guidance as having: no outpatient mental health services within the last year and two or more psychiatric hospitalizations; or no outpatient mental health services within the last year and three or more psychiatric ED visits.

[21] For example, an individual on an ACT waitlist or someone at risk of homelessness who does not meet the HUD Level 1 definition of homelessness may be suitable for HH+ without meeting any of the technical criteria.

[22] The Single Point of Access (SPOA) in New York is a centralized system that assesses individuals with severe mental health needs, prioritizes access based on urgency, and connects them to appropriate services such as care management, housing support, assertive community treatment (ACT), and crisis teams.

[23] NYS DOH, Health Home Standards and Requirements for Health Homes, Care Management Agencies, and Managed Care Organizations, May 1, 2022. p. 9.

[24] NYS OMH, Statewide OMH All Provider Meeting Hospital & Community Connections, December 12, 2023. p. 8

[25] NYS OMH, Health Home Plus (HH+) Specialty Mental Health Care Management Agency (SMH CMA) Connections to support Critical Transitions: Request for Applications, November 2023.

[26] NYS DOH and OMH, Guidance on Evaluation and Discharge Practices for Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Programs (CPEP) and §9.39 Emergency Departments (ED), October 2023.

[27] Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) are a range of services that help people with behavioral health needs live independently in their communities. HCBS programs can include personal care, home health care, and other services. In 2022, NYS transitioned a subset of four HCBS services (Community Psychiatric Support and Treatment, Psychosocial Rehabilitation, Family Support and Training, and Empowerment Services: Peer Support) into CORE, which is jointly overseen by OMH and OASAS.

[28] NYS OMH and OASAS, Behavioral Health High-Risk Eligibility Criteria, August 2023.

[29] While the Model Contract for various Medicaid models is public, the Appendix containing their approved capitation rates is blank, besides the title: NYS DOH, Medicaid Managed Care/ Family Health Plus/ HIV Special Needs Plan/ Health and Recovery Plan Model Contract, March 1, 2024. p. 470.

[30] NYS DOH, Summary of the MLR Calculation and Definition of Terms, November 2023.

[31] NYS Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare, Written Testimony Prepared for the Members of the Joint Legislative Budget Committee, Hearing Topic: FY 2022 Executive Budget Proposals, Health/Medicaid, 2022.

[32] The Boston Consulting Group, Final Report on Managed Care Organization Services As Commissioned by the New York State Legislature in Section 1 of Part P of Chapter 57 of the Laws of 2022, October 2023. p. 59.

[33] NYS DOH December 2024 reporting reflects HARP enrollment of 153,297 statewide, but does not provide the corresponding eligibility figure.

[34] NYS OMH, NYS Behavioral Health (BH) Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) and Community Oriented Recovery and Empowerment (CORE) Dashboard: County Level Data, July 2023.

[35] NYS OMH, Explanation of Initial HARP Enrollment Process.

[36] Ibid, Final Report on Managed Care Organization Services As Commissioned by the New York State Legislature in Section 1 of Part P of Chapter 57 of the Laws of 2022, p. 64.

[37] RAND Corporation, Independent Evaluation of the New York State Health and Recovery Plans (HARP) Program: Interim Report, November 13, 2020.

[38] In 2018, the State issued notice that plans would contract directly with State Designated Entities (SDEs) for the adult BH HCBS assessment, referral, and HCBS Plan of Care development for HARP members not enrolled in Health Homes. This eased BH HCBS access because CMAs were no longer the only entity able to assess eligibility.

[39] Frimpong, E., et al., Impact of the 1115 behavioral health Medicaid waiver on adult Medicaid beneficiaries in New York State, April 19, 2021.

[40] Ibid, Final Report on Managed Care Organization Services, p.11.

[41] NYS DOH, Care Management For All, March 2017.

[42] Technically, HIV SNPs have existed since 2003, but their growth exploded in 2011 when many groups (including HIV-positive members) that had been exempt from earlier managed care mandates were required to enroll in managed care plans.

[43] Ibid, Health Home Standards and Requirements for Health Homes, Care Management Agencies, and Managed Care Organizations, p. 36.

[44] NYS DOH, eQARR – An Online Report on Quality Performance Results for Health Plans in New York State.

[45] NYS DOH, Health and Recovery Plan (HARP) Value Based Payment Quality Measure Set Measurement Year 2024, February 2024.

[46] NYS DOH, Health and Recovery Plan Value Based Payment Arrangement Fact Sheet, February 2024.

[47] NYS OMH, Specialty Mental Health Care Management in Health Home (Adults).

[48] Wetzler, S., et al., Impact of New York State’s Health Home Model on Health Care Utilization, March 14, 2023.

[49] NYS DOH, Managed Care Organization (MCO) Directory by Plan, September 2024.

[50] The Milken Institute School of Public Health and Amida Care, HIV Special Needs Plans in the New York State Medicaid Program, October 2021. p.10.

[51] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, North Carolina Tailored Care Management/Health Home State Plan Amendment (SPA), August 19, 2022.

[52] The other two integrated managed care plan types are “Standard Plans” and “Children and Families Specialty Plans.”

[53] Ibid, North Carolina Tailored Care Management/Health Home State Plan Amendment (SPA), p. 2.

[54] The Commission on Community Reinvestment and the Closure of Rikers Island, Commission on Community Reinvestment and the Closure of Rikers Island Report, 2021.

[55] Ibid, HIV Special Needs Plans in the New York State Medicaid Program, p. 5.

[56] Ibid, p. 3.

[57] ““Comprehensive HIV Special Needs Plan” or “HIV SNP” means an MCO certified pursuant to Section forty-four hundred three-c (4403-c) of Article 44 of the PHL which, in addition to providing or arranging for the provision of comprehensive health services on a capitated basis, including those for which Medical Assistance payment is authorized pursuant to Section three hundred sixty-five-a (365-a) of the SSL, also provides or arranges for the provision of specialized HIV care to HIV positive persons eligible to receive benefits under Title XIX of the federal Social Security Act or other public programs.” Ibid, Medicaid Managed Care/ Family Health Plus/ HIV Special Needs Plan/ Health and Recovery Plan Model Contract, p. 20.

[58] Ibid, p. 6.

[59] Ibid, p. 10.

[60] In HIV-SNPs, primary care providers (PCPs) must have specialized training or expertise in HIV care, ensuring that enrollees receive competent and comprehensive care. This approach could be replicated in a behavioral health-specialty plan model by requiring PCPs to have training in mental health and substance use disorders, or participate in the Collaborative Care Model, to foster better integration of physical and behavioral health services.

The post Reforming Care Management for Adults with Behavioral Health Needs in New York Medicaid appeared first on EMPIRE REPORT NEW YORK 2025® NEW YORK’S 24/7 NEWS SITE.