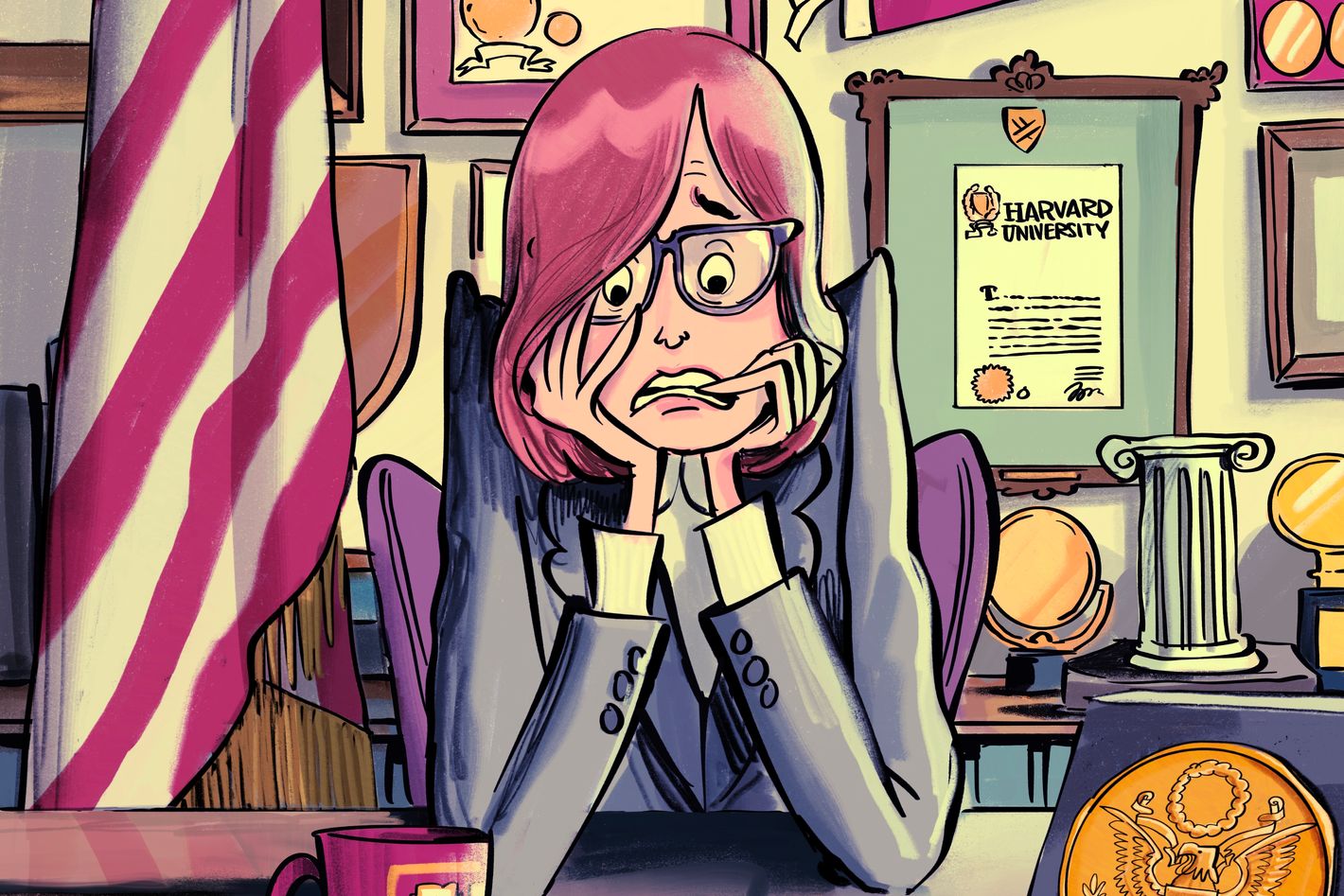

Illustration: Zohar Lazar

Lauren was at her desk when the email arrived, as bland and curt as it was apocalyptic. “Good morning, CFPB staff,” it read. “Employees should stand down from performing any work task. Thank you for your attention on this matter.”

It was a few minutes before 9 a.m. on Monday, February 10. “I just got physically nauseated,” Lauren told me. (I’ve used a pseudonym to protect her privacy.) The message was from Russell Vought, the acting head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, where Lauren had been an exceptional performer for more than a decade. Since Donald Trump’s reelection, she had been reassuring her staff that their work would go on; sure, the new administration would instruct them to quit some projects, but perfectly valid ones would take their place. This email made it clear she’d been naïve. Their jobs would be vaporized.

Though a judge has stalled the matter, Lauren puts her odds of termination at 99 percent. She has never been fired before. The concept of joblessness seems faintly ridiculous if you look at her magna cum laude résumé: degrees from Columbia and Harvard, editor-in-chief of a law journal, prestigious fellowships, so many academic and professional honors that she could not, when we spoke recently, recall them all.

In their campaign to eliminate hundreds of thousands of government jobs, Trump and Elon Musk have portrayed federal workers as lazy and wasteful, skilled only at committing outright fraud. But there are a lot of Laurens in Washington. At State and at Justice, at CFPB and at USAID, the capital is teeming with them — academically ambitious and impeccably credentialed types who have forsworn more lucrative work in the private sector because there is no better place to make an impact. Many members of this tier have never known anything but success, and suddenly they are facing not just unemployment but possibly being unemployable. It’s an unimaginable situation for those who have played the game of meritocracy by the rules, at the highest levels, for the purest reasons and the lowest compensation.

“It’s hard to even put into words. I feel so devalued,” said Lauren. She’s dreading the inevitable task of competing with her colleagues for the scarce positions that exist in their area of expertise: “Everyone who’s talented in this field is also looking for a job. It’s terrifying, and it does sort of make you question what you’ve been doing all along, that you believed in this project.” States have consumer-protection watchdogs but with a fraction of the resources she’s used to wielding; becoming a compliance officer at a big bank may not be an option if there is no longer a regulator to comply with. This wasn’t part of her plan.

Another senior financial regulator who assumes the worst told me, “It’s possible that I might not get back on my feet.” He has two Harvard degrees, both cum laude. Trump’s assault on the civil service is hitting him pretty hard. “I am witnessing a fundamental change in who I thought we were as a country and what I thought about how the world works, the rules of the game,” he said. “And that shakes you existentially. It represents a larger change in who you think we are as a people. That’s a bigger thing to grieve because let’s say you believe in the rule of law and you are working here because you want to make sure people follow the laws. You think, Well, if I get fired, I can always go out and work on the industry side. What if industry realizes we don’t need to follow the laws anymore? It’s not that you don’t have a job — you don’t even have a career. But also your idea that this is a country built on laws could itself be now, suddenly, at risk.”

Psychologically maiming the “deep state” is an explicit goal of the layoffs. “We want the bureaucrats to be traumatically affected,” Vought said in a closed-door speech that ProPublica obtained late last year. “When they wake up in the morning, we want them to not want to go to work because they are increasingly viewed as the villains.” But when I spoke to a dozen elite federal workers at a range of agencies — people with multiple diplomas and high-status jobs — I encountered not just heartbreak but bitterness, scorn, denial, and paranoia.

“It’s pretty infuriating,” said an expert in postwar governance and counterinsurgency. His career highlights have a whiff of Tom Clancy: His master’s was in conflict management, he has been evacuated from war zones twice, he was once detained by an authoritarian regime, and he survived a shooting attempt inside an armored vehicle. In D.C., this is currency that far exceeds any level of pay a person might draw in the private sector. “You just see some of these kids’ eyes get huge when you talk about peace negotiations and meeting with rebels,” he said. “There’s always been a pipeline of people who just desperately want to do this.” But with drastic cuts planned for the State Department and USAID, where Trump wants to eliminate more than 90 percent of foreign-aid contracts, that pipeline may run dry.

I asked the expert, who’s only in his 40s, what job he will seek next, given his subspecialization in a particular part of the globe. “I have no idea,” he said. “I’m the only one who’s done this.”

Given their networks, some of the civil-service elite will easily find new jobs. Plenty of them turned down better-paying gigs to come to Washington in the first place. “I’ve had four people try to recruit me already,” a triple-degree polylinguist in the foreign-policy apparatus told me. “I don’t need this job. I chose this job. My feeling these past couple weeks is like, Look, if they fire me, they fire me. Frankly, I think it’s a loss for America. It would be sad for me because I love my job. But I’m not afraid for me. I’m defiant. I’m going to show — ”

His wife, another prestige-background Fed, interrupted. “Don’t say defiant,” she said. “You’ve got to be careful. This is what I’m talking about. It’s scary,” she added, addressing me now. “I’ve never used Signal in my life before. Now every single private conversation I have with any single person in D.C. is on Signal. Literally everything. Everyone is terrified. There are rumors that any Teams conversation you have on your computer can be recorded without your knowledge and transcribed and searched by AI for any signs of non-allegiance.” The couple are considering leaving the country.

After I hung up with her husband, she called me back, encrypted. “I think a lot of people outside of D.C. aren’t really recognizing what’s happening,” she said. “The first couple of weeks, I would get texts from people like, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry about your job.’ And I was like, ‘This is not about my job; I can get another job. This is about the country. You should be sorry too.’” She said walking past the Capitol dome used to feel exciting. Now she just finds it ominous.

Another double-Ivy castoff — this one Harvard-Yale, a senior attorney at the Department of Justice — described group chats with colleagues that are full of “this combination of despair and rage and impotence.” Everyone is sickeningly aware that these are the exact emotions that the people demolishing the government want them to have. “The thing that I feel the most is guilt,” she said. “I feel like I made it easy for them by not fighting back.”

She considers her old position irreproducible, a “fantasy job” with driven colleagues who inspired her. It’s all a bit difficult to explain to the cynics and realists who dominate the legal profession outside Washington. “There’s this childish idealism that I do feel embarrassed to say in front of my friends,” she says. “The childish idealism of I’m serving my country.”

She takes no solace in the possibility that within a year or two she might be earning a fat salary at a private firm. Money was never the point. As Musk, Trump, and their allies inveigh against “the elites in Washington,” they draw upon outdated ideas about who exactly composes the deep state. The slightly romanticized story Washington tells itself is that the civil service was once thick with do-gooders from the Establishment, with drawers full of diplomatic passports and neckties from St. Mark’s. But that set, to the extent that it ever really existed, has long since been supplanted by strivers and meritocrats from more modest backgrounds.

“Many, many, many of my colleagues are first-generation grad school, and some of them are first-generation college,” the attorney said. “The most you’re going to make at DoJ is less than literally a first-year associate at a big firm. And these are years that you could have been rising up the corporate ladder. It’s not like you can easily go, Okay, I’m done. Now I’m going to be a partner after 15 years at DoJ.”

A different DoJ veteran, who resigned rather than work in the Trump administration, recalled interviewing for a government job while clerking for the Supreme Court, which could have entitled him to a gigantic bonus at a white-shoe firm. “They said, ‘Talk about your commitment to public service.’ And I was like, ‘Commitment to public service? I just put a giant pile of money on the table and lit it on fire!’ Everyone started laughing, and I was like, ‘No, but really — that’s what I think.’ It was $350,000 or something.”

Another newly jobless civil servant, this one a Ph.D. who was fired from the Department of Health and Human Services by form letter, was the first in his family to attend college. His grandmother recently sent him money to buy groceries. Lauren at the CFPB described trying to be candid with her 7-year-old about what their family might go through if she’s unable to get a new job. “He has a birthday coming up, and we’re trying to set expectations a little lower,” she said. “Talking to him about moving, I realized, was just way too much. It’s hard to moderate when you are so upset.”

The people I’m talking about are not unicorns. You come across their kind frequently if you spend any time living or working in Washington, and the fact that they’re being binned en masse puts the lie to the idea that the DOGE effort is sincerely interested in efficiency. In the case of, say, a former SCOTUS clerk who could have become a litigator at a top firm but is instead toiling as a Justice Department attorney, America is getting something like $700,000 worth of brains for less than a third of the price. The biggest loser in all of this is us — the people who benefit from a civil service studded with intellect and conviction. “The impact is always on the margin,” said Don Kettl, former dean of the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy. That is, it’s the person with just a little more oomph who can crack a problem open.

But explaining the value of government to those who want to burn it down is useless — a reality that some alpha do-gooders are still struggling to accept. “This sounds crazy, but I understand that I am, in a way, part of the Trump administration,” said a Harvard-educated lawyer at the Securities and Exchange Commission. “As vile as that is to me, I’m prepared to do the good work of the Trump administration with respect to securities enforcement. And instead of harnessing that and putting me to work, you are basically threatening to fire me and alienating me and offending me. That’s just crazy. Set aside that I’m a highly educated lawyer who has put aside more lucrative positions for this job. Put all that aside — you’re just not capitalizing on a resource that can do the work you want to do.”

Like everyone else I spoke to, this lawyer is profoundly demoralized by the prospect of losing the opportunity to work on behalf of the American people. “I was at a huge international firm,” he said. “I was doing securities litigation at the absolute highest level that a person can do that work. I chose the SEC because there is no better place to practice securities law. If you’re a true believer that companies and individuals need to be held to account, you can work on the private-sector side and do 10b-5 cases where you allege private violations of the securities laws. But there’s nowhere else you can go and actually enforce the securities laws of the United States than the commission. And it’s awesome. It’s exciting. It’s amazing.”

He kept up his riff, like a monologue from the saddest episode of The West Wing. “The cases that come across my desk, somebody — at least one American and usually many Americans — was harmed, was defrauded, was taken advantage of by unscrupulous investment advisers or broker-dealers, or was convinced through lies to hand over their money. I get to practice at the highest level of lawyering, but I also — independently — get to fight for those people, and get disgorgement for them, and get justice. It’s important,” he said and let out a bitter laugh.

His pink slip, he knows, could come any day now.

Related

All the Firing, Layoffs and Resignations We Know OfInside Elon Musk’s Killing of USAID