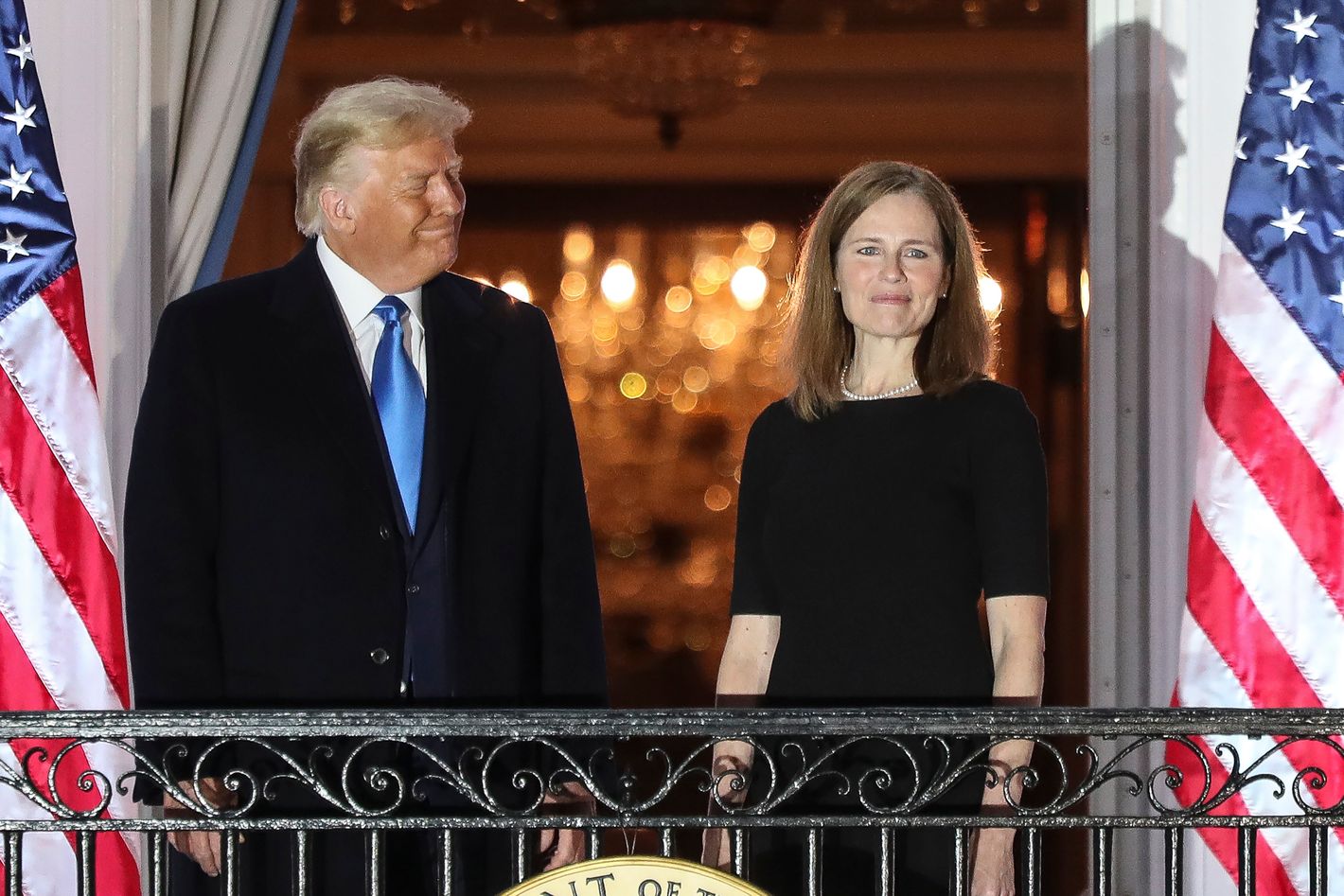

Photo: Oliver Contreras/The New York Times/Redux

The path to women’s liberation has always been blocked by other women. Before Amy Coney Barrett rose to the Supreme Court or Marjorie Dannenfelser began her war on legal abortion, there was Phyllis Schlafly, that self-styled paragon of wifely submission, and Anita Bryant, the unrepentant homophobe. In Right-Wing Women, the late feminist writer Andrea Dworkin skewered them and the culture of male violence they served. Now that Schlafly’s heirs are in power, we owe Dworkin reevaluation, or so the argument goes. “Few writers are pilloried so confidently by people who do not really know what they said; few writers provide, as a consequence, so many disorienting surprises,” the writer Moira Donegan argues in a new foreword to the reissued book.

Dworkin published Right-Wing Women in 1983 as second-wave feminism faded and the Reagan revolution got underway. There was something unfashionable about her, even then. Her scalding analysis of woman-hatred ran counter to the Moral Majority’s tender visions of the traditional white family, anchored by a mother in the home. Feminists, too, regarded her with suspicion if not hostility, and for good reason. In the porn wars years earlier, Dworkin sided with the censorious Christian right over many of her feminist peers, a decision that would undermine her work for the rest of her life. By the time she died in 2005, most people knew Dworkin the caricature, not Dworkin the writer.

Like the rest of her work, Right-Wing Women is a hammer blow. “From father’s house to husband’s house to a grave that still might not be her own, a woman acquiesces to male authority in order to gain some protection from male violence,” she asserted, and who can fault her? The right-wing woman is ascendant, and with her rides the incel, the woman batterer, and the rapist. Andrew Tate’s former attorney, Paul Ingrassia, now works for Donald Trump, an accused rapist, and so does Pete Hegseth, who has been accused of sexual assault and abuse himself. Hegseth hired Sean Parnell, whose ex-wife once testified that he choked her and abused their children. Dana White, the chief executive of the UFC and a prominent Trump ally, allegedly hit his wife and embraced Tate and his brother Tristan at a recent event. Texas lawyer Jonathan Mitchell represents men who are outraged over their partners’ abortions, and some women have accused his clients of domestic abuse.

Women are in danger, and they know it. The right-wing woman knows it too and, Dworkin wrote, strikes a bargain to save herself. “The political Right in the United States today makes certain metaphysical and material promises to women that both exploit and quiet some of women’s deepest fears,” she argued. “These fears originate in the perception that male violence against women is uncontrollable and unpredictable.” Today’s tradwives agree to bear children, stay at home, and obey their husbands because the alternative is too frightful for them to contemplate, because the right wing tells them that it is their nature and because it’s what they want to do. They believe abortion, contraception, and queerness prevent them from finding true satisfaction as women, so each must be destroyed. If they’re bored enough, or zealous enough, they can follow Schlafly and Bryant and sell their choices to the masses. There’s always TikTok.

In videos and on podcasts, right-wing women say they need men more than they need feminism. Of course, the opposite is true. We need feminism, but there are many feminisms, and they aren’t all fit for purpose — any reevaluation of Dworkin must reckon with the full scope of her work. Though her defenders will sometimes admit some flaws in her thinking, they say her critics have judged her too harshly. She did not write that all heterosexual intercourse is rape, as is commonly reported, and whatever her flaws, her feminism had teeth. The rise of Trump, and later the Me Too movement, helped revitalize interest in Dworkin, whose excoriations of male brutality no longer seemed so outlandish. After all, what had sex positivity accomplished for women? “In her singular scorched-earth theory of representation, pornography was fascist propaganda, a weapon as crucial to the ever-escalating war on women as Goebbels’ caricatures were to Hitler’s rise,” Johanna Fateman wrote in the introduction to Last Days at Hot Slit, a 2019 collection of Dworkin’s work. In 2021, the academic Claire Potter wrote that Me Too had “opened the door to a long-overdue recognition of Dworkin’s contributions to how we understand the politics of sex and gender,” adding, “I have always believed that part of the hostility that Dworkin aroused had something to do with a clarity of mind that terrified people who shy away from difficult and dangerous thoughts.”

It’s an attractive logic. Twenty years after Dworkin’s death, feminists have few friends and little institutional power. They certainly cannot look to the Democratic Party for aid, as members dither over rhetoric and strategy. A handful of Democratic women wore pink to Trump’s State of the Union address because it is “the color of women’s power, of persistence and of resistance,” Representative Teresa Leger Fernandez told the New York Times. The pink-clad electeds held up signs as Trump rambled; it was Representative Al Green, not in pink, who interrupted the speech. (Some Democrats joined Republicans to censure him later.) Other Democrats try to appease the right by sacrificing trans girls and women on the altar of political expediency. With fascists on one side and quislings on the other, a militant response is overdue. Enter Dworkin, whose relentless anger and imaginative prescriptions can seem like the antidote not only to the right wing but to mainstream feminism itself, which told women that liberation ran through the Capitol and the courtroom and the corner office. Dworkin did not seek parity with men, but rather a new world altogether.

The pursuit of power for its own sake leaves most women behind, and the politics of compromise brings even the girlboss to her downfall. Right-Wing Women reappears in a moment of pitched anti-feminist backlash, as corporate America abandons all pretense of equal treatment and abusers of women fill the government. Women marched, rallied, and told their stories, but no hashtag is a match for misogyny. “No matter how often these stories are told, with whatever clarity or elegance, bitterness or sorrow, they might as well have been whispered in the wind or written in sand; they disappear, as if they are nothing,” Dworkin wrote. Male outrage drowned out female pain. As she put it, “The tellers and stories are ignored or ridiculed; threatened back into silence or destroyed, and the experience of female suffering is buried in cultural invisibility and contempt.”

Lately, pundits and policy wonks speak of men — their loneliness, their resentment, their decline — often presented as problems for women to solve. One popular theory says American men are moving to the right because they have been abandoned by liberals and alienated by feminism. The solution, of course, is for women to marry them anyway. Men need marriage and children to be happy, which is to say they need women; the worthiness of a man matters less to a pro-natalist than his fertility. Even a woman who seeks heterosexual marriage must know her place or be condemned. On the latest season of Love Is Blind, a contestant left her fiancé at the altar because he attends an anti-gay megachurch, and the right wing erupted. “This man dodged a bullet,” posted Isabella Maria DeLuca, a January 6 rioter. “Liberal women are INSUFFERABLE & MISERABLE,” posted Morgonn McMichael, who works for Charlie Kirk’s Turning Point USA.

Marriage is no sure refuge from male violence, and it can often become a trap, as Dworkin knew well. She endured molestation as a child and sexual violation during her incarceration as a war resister, only to marry a man who beat her savagely, once in front of her apathetic parents. In Right-Wing Women, she wrote almost sympathetically of Bryant, who was married to a controlling Evangelical husband. “Bryant, like all the rest of us, is trying to be a ‘good’ woman,” she argued. Yet Bryant was responsible for her own choices and by all accounts died a bigot. There is no easy way to separate the right-wing woman’s convictions from her victimhood, though we often try to do it anyway. In the silence of Usha Vance, some look for evidence of dissent, as if a woman of her obvious intelligence could not possibly agree with her husband’s retrograde politics. Vance, like Bryant, is oppressed and oppressor at once.

Portions of Right-Wing Women remind us that the Trump era has old roots. The Guardian reported earlier this month that an upcoming pro-natalist conference will feature eugenicists and purveyors of race science who believe women must have babies, but in the right way and with the right men. The argument is familiar, and so is the racism behind it. Dworkin recalled her encounters with a delegation of anti–Equal Rights Amendment women from Mississippi. The Ku Klux Klan said it controlled the delegation, she wrote, and a man who accompanied them said he held a powerful role in the white-supremacist group. “He said that his wife had wanted him to be there to protect women’s right to procreate and to have a family,” she added.

Dworkin concluded later in Right-Wing Women that an extermination or “gynocide” may be on the way, though it was not inevitable. A rigorous thinker, she diagrammed a system of crimes against women to help her readers break free of the same. Her writing was one more act of optimism, shaped by her deep conviction not only in the necessity of liberation but in its possibility. In the years since her death, some feminists have identified a prophetic quality to her thinking, although that, too, risks caricature. A prophet is a divine vessel, and Dworkin was not that.

One of the principle functions of the right-wing woman is to police female sexuality and reproduction, and Dworkin’s logic ultimately pushed her into a similar role. In Right-Wing Women, Dworkin attacked sex work, pornography, and reproductive technology with the same ferocity she applied to Schlafly’s ilk. “Motherhood is becoming a new branch of female prostitution with the help of scientists who want access to the womb for experimentation and power,” she wrote, but the truth is somewhat more complex. For conservatives who defend technologies like IVF, science is another way to bind women to motherhood, but it can also detach reproduction from compulsory heterosexuality, and it offers women a way to bear children on their own terms, which is why it has always been in danger from some factions of the right wing. Dworkin admitted the irony, but as with her fight against pornography, she stood firmly on reactionary ground.

If there is a gynocide to come, as she feared, it would be carried out by the same forces who want to ban IVF, pornography, and sex work. The writer Sophie Lewis has called Dworkin’s thinking an “enemy feminism,” an obstacle to the very liberation she sought. “Did Dworkin herself not see the contradiction between her unjust arrest and subsequent rape at the hands of the state, and her apparent faith that this same coercive apparatus could be wrangled into the service of women?” wrote the philosopher Amia Srinivasan in 2022. “Even if we grant, with Dworkin and other radical feminists, that sex work cannot be understood outside the frame of gendered hierarchy, what does it mean to ignore sex workers’ near-universal insistence that the criminalisation of their trade makes their lives less liveable?” That’s not an abstract question. The answer has life-or-death consequences.

With the right wing in power, the pursuit of liberation only becomes more urgent. “Will it take a hundred fists, a thousand fists, a million fists, pushed through that circle of crime to destroy it, or are right-wing women essentially right that it is indestructible?” Dworkin asked. “The freedom of women from sex oppression either matters or it does not; it is essential or it is not.” We must agree that it is essential. In doing so, we must also understand why liberal “war on women” rhetoric has failed. Misogyny is one reason, but misogyny serves a purpose, and today’s anti-feminist moment was orchestrated by political forces that rely on our collective submission. The right wing tells all of us to bargain against our own liberation. They tell men that women’s advancement deprived them of economic and emotional security, and they tell women that safety depends on the prosperity of men. All they can offer is hierarchy. Without meaningful political alternatives to that argument, misogyny will become more attractive, and the ranks of the right-wing woman will grow. Dworkin knew that women need a revolution, a feminism of fists. If it’s going to succeed, it will have to be more transformative than even she imagined.