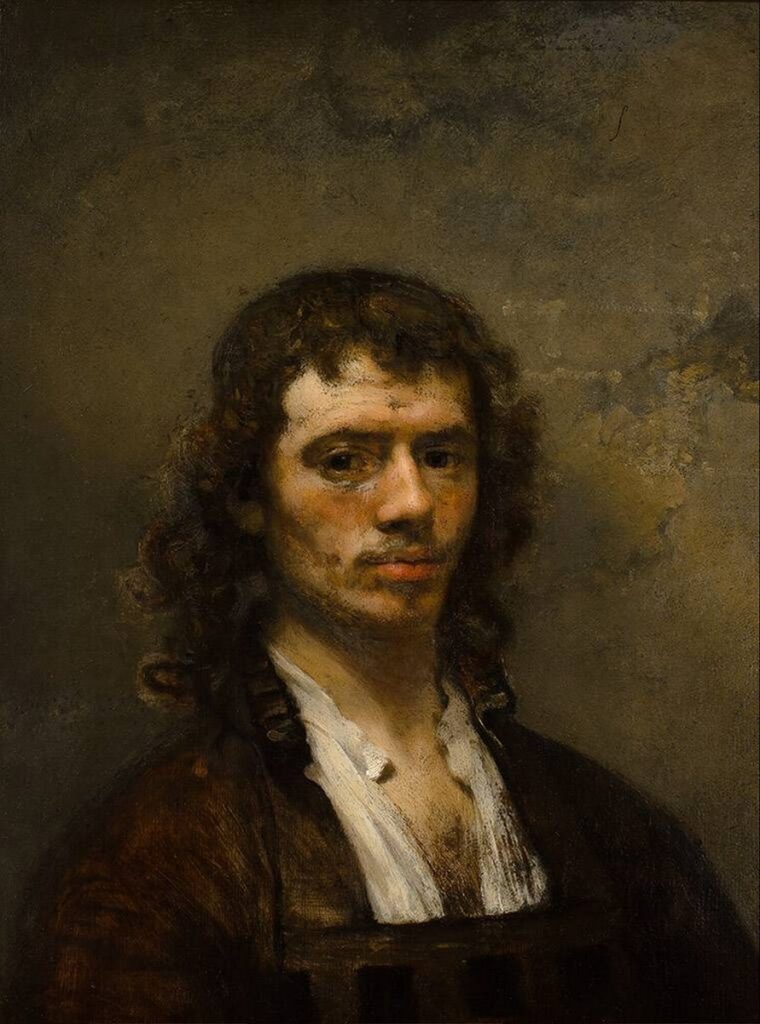

Rembrandt worked slowly. The layers of time in each painting, the atmosphere in each layer, the depth and glow—these take time. He had fifty years to develop his indelible touch, leaving a legacy of masterpieces. His best and favorite student, Carel Fabritius, had (at most) 15 years to develop his artistry, dying at the age of 32. He left only a dozen paintings and nine drawings.

Born in 1622 during the Dutch Golden Age, Fabritius sits beautifully between Rembrandt and Vermeer. He was a member of the Delft School, but didn’t paint domestic scenes like Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch. He experimented, lightening his backgrounds, exploring spatial perspective, inventing scenes, playing with mythology. He matured swiftly, steadily, creating works that dazzle in their technical ability, refinement, and beauty.

His father was an amateur painter, and his two brothers also took up painting. The earliest known painting by Carel is The Beheading of John the Baptist, 1640, created when he was 18. At the time, he was working in Rembrandt’s studio and already had a gift for conveying attitude in his characters. The chiaroscuro is confident and radiant, contrasting the white of Salome’s ermine collar with the old woman’s raised finger; the executioner’s ruddy face with the pale head on the platter. The contrasts are also distinct and poignant in the eyes of each person, clearly showing their emotions.

SEE ALSO: Curator and Art Historian Camille Morineau On Finding the Women Artists of the American West

Like Rembrandt, Fabritius worked in complex layers, often modelled with a heavily loaded brush. Using a brown ground, both artists worked from dark to light. Instead of an exact imitation of form, they gave suggestions of form which were sometimes thought to be unfinished paintings. This independence from the image created emotion and a spiritual quality, like Fabritius’ Hagar and the Angel, 1643. The details in the background, the delicacy of the hands, the glow of the skin and the immense unfurled wings of the angel reveal a mastery of technique for one so young. Rembrandt and his school frequently used the story of Hagar from the Old Testament.

Fabritius’ few paintings are exhibited in different museums and collections around the world, making it difficult to see his works in person. I was lucky to see one of his paintings, Mercury and Aglauros, 1645, at the MFA, Boston. Here are the gold highlights that are famous in his teacher’s work and evidence of Fabritius’ coming into his own genius. In this obscure classical myth, the god Mercury turns the mortal Aglauros to stone because she tries, in her jealousy, to bar Mercury from his beloved. Fabritius chooses to depict the moment before she turns to stone as an intimate human story. The dramatic lighting gives volume and import to the work, as well as the details of Mercury’s snake, helmet, lightning bolts on his heels, the red sash, and the flowing fabric of their dress.

At the National Gallery, London, hangs A View of Delft, with a Musical Instrument Seller’s Stall, 1652. The scene is a panoramic perspective of Delft, with the seller and his lute in the foreground. Clearly, Fabritius loved to experiment and push beyond what his contemporaries were doing. He used thin, delicate glazes over areas of impasto, creating depth, light and shadow, fluidity and rich textures. Vermeer followed soon after.

In the last year of his life, Fabritius painted his two most extraordinary paintings. One, The Sentry, 1654, is a street scene right out of Don Quixote. There is the drunk or sleeping or otherwise slacking soldier, his trusted dog waiting patiently for his master to awaken. In the background is an arched bridge, stone column, curving street and overhead staircase leading to a dark cavern. Above the bridge is a stone relief of a saint with his pet pig. Even the vibrant greenery, the tree through the bridge, and the shadows of the man and of his dog reveal rare, advanced talent. Here is a tender sadness surrounded by classical beauty.

But perhaps the most famous of Fabritius’ paintings is The Goldfinch, also 1654, now at the Mauritshuis, The Hague. During the time he painted this, 132,000 migrating goldfinches were sold in England as songbirds. Fabritius’ poor bird is chained to his perch. The painter had a rare ability, as in The Sentry, to create pathos wrapped in beauty. You can see each stroke, each wing feather, a patch of red around the beak, the streak of yellow. The bird is looking straight at the viewer, filled with emotion.

In the two decades between 1640 and 1660, when the artist was active, it is estimated that over 1.3 million Dutch pictures were painted—yet only a handful of Fabritius paintings remain. The volume of production meant that prices were low. Vermeer owned three paintings by Fabritius and hung them on his wall. It is unknown which ones. You can see Fabritius’ influence in Vermeer’s work; the crumbling plaster, the light and shadow, the startling compositions, the intimacy of scene and his own view of Delft. Fabritius had his studio in Delft in a gunpowder factory, and he died during the ‘Delft Thunderclap,’ when 90,000 pounds of gunpowder accidentally detonated. A quarter of the city was destroyed in the explosion, as well as Fabritius’ work, his precious life and the masterpieces that could have been.