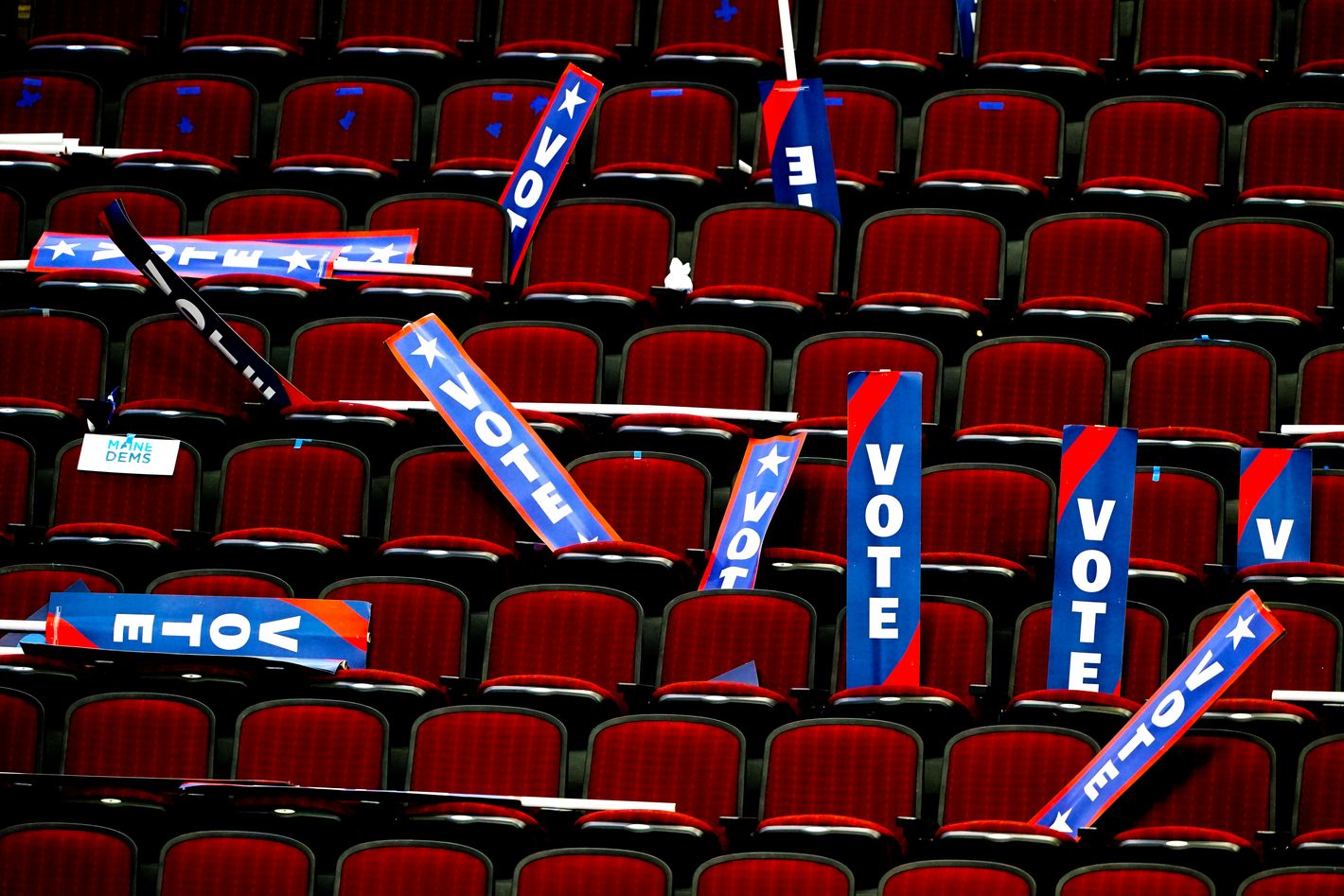

Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times/Redux

For the first time in two decades, it is impossible to predict who the next Democratic nominee for president might be. Three straight election cycles produced three flawed nominees who were firmly backed by their predecessors. Hillary Clinton was Barack Obama’s preferred successor, and led in just about every single poll over her theoretical and literal competition. Joe Biden seized the nomination four years later, thanks in part to Obama’s 11th-hour intervention to force several competitive center-left candidates, including Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, out of the primary ahead of Super Tuesday. In 2024, following Biden’s implosion, Kamala Harris became the first Democratic nominee in more than a half-century to achieve that status without winning a vote in any of the primaries.

Now it’s all blown open. This makes some Democrats nervous. The party is bereft of a single leader and seems adrift, struggling to respond to Trump’s assaults on the federal bureaucracy and the civil rights of legal residents. The party itself, in most polling, is widely unpopular, and no single course of action feels especially satisfying. Many Democrats wanted Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader, to refuse to help Republicans keep the government open. His decision to pass a continuing resolution with GOP support has enraged many elected Democrats and activists, especially on the left. But Schumer understood the alternative was no better: Trump and Elon Musk might have reveled in a shutdown, using it as a pretext to purge enormous numbers of government workers. Ken Martin, the new chair of the Democratic National Committee, doesn’t seem like the sort of inspirational figure capable of leading the party out of the wilderness.

But the state of play isn’t as grim as it looks. The shadow primary underway for 2028 is exactly what Democrats need: a robust contest over ideology and ideas that will be waged in the public square. The best Democrat will win. It was under these conditions that Barack Obama, still in his first term in national office, ascended to the presidency. Since then, for a variety of reasons, Democrats have been allergic to such competition.

It will be the most public and natural way to define what the future of the Democratic Party might look like. There will be no single interest group or power broker who can boost one candidate to victory at the expense of the rest of the field. Centrist, progressive, populist, or something else entirely — all ideological factions will get the open playing field. When George W. Bush defeated John Kerry in 2004, there were very few pundits calling for the Democratic Party to nominate a Black former law professor who was strongly opposed to the Iraq War. The primary sorted that out. Now, Democrats will get that opportunity again.

There’s a long roster of governors, senators, members of Congress, and celebrities who can take the plunge. A short list includes Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer, Illinois governor J.B. Pritzker, Maryland governor Wes Moore, Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro, Kentucky governor Andy Beshear, and California governor Gavin Newsom. Senator Christopher Murphy of Connecticut and Ro Khanna, a Silicon Valley congressman, seem likely to announce. For Democrats hungry for wealthy, famous outsiders, billionaire Mark Cuban and Stephen A. Smith, the ESPN commentator, could be viable. Pete Buttigieg will probably run again. Both Harris and her old running mate, Tim Walz, might be in the mix. For those nostalgic for bruising centrists, Rahm Emmanuel is floating a trial balloon.

Tim Walz and Rahm Emmanuel are very different kinds of Democrats, as are Ro Khanna and Andy Beshear. Democratic voters will get to decide, fully, what the future of their party will look like. It will not be a sham primary like 2024, when it was left to Dean Phillips to wage a hopeless campaign against Biden, or even 2016, when Clinton had hoovered up so much institutional backing that only Bernie Sanders, a septuagenarian from Vermont, could wage a viable campaign. This will be much more wide open. Republicans, in 2015 and 2016, did not quite imagine their party would be remade in the image of Trump — that is the messy side of democracy, after all, the outside agent who proves more popular than the institutional insiders. But a fear of a Democratic Trump isn’t an excuse to avoid competition. All of this is healthy.

If Harris, for example, wants to be the nominee once more, let her get battle-tested with a long primary through the early voting states. Primaries are vital for shaping candidates: They learn, like Obama once did, to charm voters on an intimate level and sharpen their arguments for why they should lead the most powerful nation on Earth. Considering the stakes for 2028, when the Democratic nominee is likely to be pitted against J.D. Vance or another Trump-aligned Republican, the party can’t afford to trot out another middling contender who will dodge the media and fail to make a coherent case for themselves. In the meantime, the 2028 primary will allow the eventual nominee to emerge organically and excite, on a grassroots level, an electorate that is going to be deeply weary of Trump.

One question hanging over the primary that Martin at the DNC will have to resolve is which states vote first. In 2024, Biden reengineered the primary calendar to drop the Iowa caucuses from the start of voting and make South Carolina, not New Hampshire, the very first state to vote. This enraged Democrats in the Granite State who have touted their first-in-the-nation status for decades. Biden boosted South Carolina as a favor to his close ally, Jim Clyburn, and as a way to ensure a primary threat against him was blunted. There was also a social-justice thrust for backing South Carolina, since the state’s Democratic electorate is largely Black. The trouble with keeping South Carolina at the front of the calendar is the state’s actual conservatism: If Black voters lean left, South Carolina itself hasn’t backed a Democrat in a general election since Jimmy Carter. Labor unions were also uncomfortable with the South Carolina pick because the state itself is fiercely anti-union.

Either way, Martin will be free to make the decision without interference from any of the Democratic grandees of the recent past, whether it be Biden, Obama, the Clintons, or Harris. The older generation will be unable to dominate the future affairs of the party. This is how it should be.