There are many art spaces in Los Angeles, but very few honor women. That’s what makes the newly opened Corita Art Center in the downtown Arts District so special. Dedicated to the artist, activist and art professor Corita Kent—once known as Sister Mary Corita and, more colloquially, the Pop Art Nun—the center will elevate her legacy of art making and social justice advocacy through exhibitions and public programming, artwork loans and the preservation of her archives.

Kent was born Frances Elizabeth Kent and took the name Sister Mary Corita when she entered the Immaculate Heart of Mary religious order at eighteen before pursuing a bachelor’s degree at Immaculate Heart College and then joining the university’s art department faculty. While teaching, she earned a master’s degree in art history from the University of Southern California and taught herself printmaking. Her earliest works were religious in nature, but as Pop swept the art world, she began to borrow themes from advertising and secular music and literature and, as the 1960s progressed, her output became more political. One 1964 print, the juiciest tomato of all, was both a play on the Del Monte tomatoes slogan and a call for the church to modernize its view on the Virgin Mother.

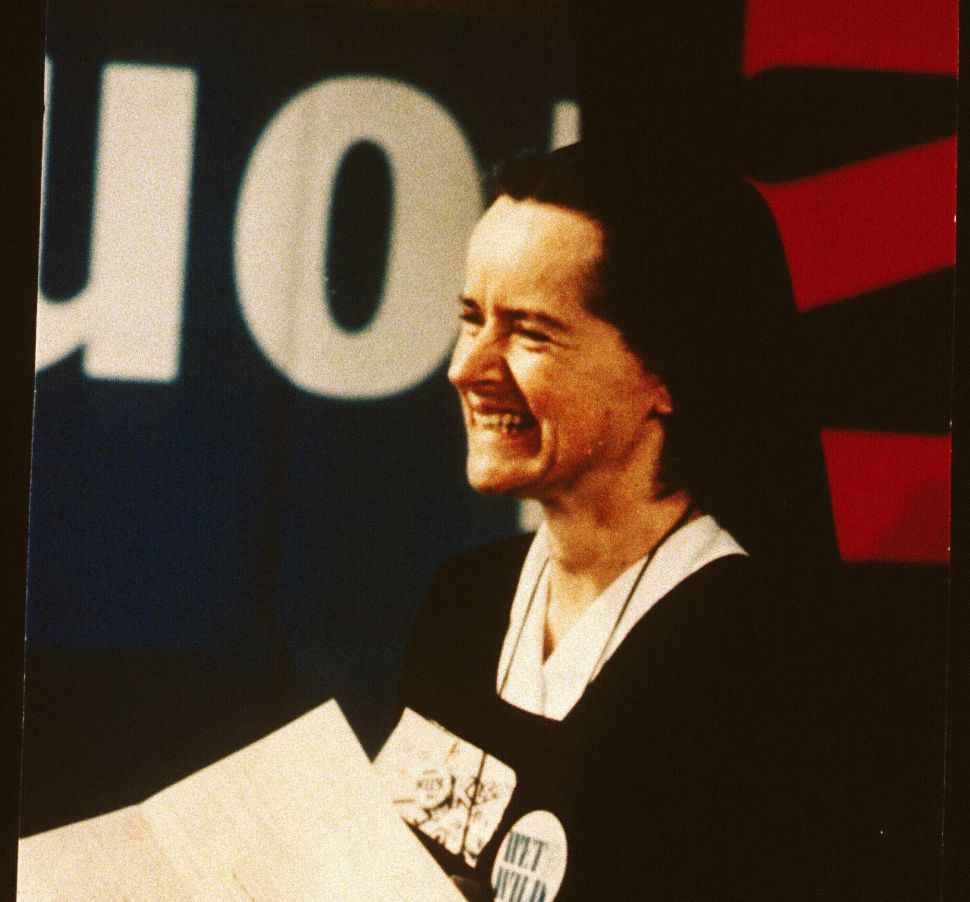

While her name doesn’t carry the same weight as those of contemporaries like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Kent’s brightly colored prints that combined popular culture with societal and religious critiques were shown at more than 230 exhibitions in the 1960s. She was named a woman of the year by the Los Angeles Times in 1966. And she made a splash in 1967 when Newsweek put her on the cover of their magazine wearing her coif with the headline, “The Nun: Going Modern.”

But she was more than just a nun, of course. Kent was a significant figure in American graphic arts in her own time. She was also a fiery advocate for change, creating thousands of posters, murals and serigraphs in support of civil rights, feminism and the anti-war movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s. And she was a rock star human being who is largely remembered for what she gave, loved by her students, respected by her contemporaries and counting among her friends icons like Charles and Ray Eames, Daniel Berrigan, John Cage and Anaïs Nin.

To wit, the Corita Art Center is not itself new—it was first founded in 1997 in a small hallway on the Immaculate Heart High School campus. On International Women’s Day (March 8), it officially moved to its own dedicated space in the L.A. art district at 811 Traction Avenue.

SEE ALSO: Shana Hoehn Explores the Uncanny Dichotomy Between Suffocation and Shelter in L.A.

As we face a new era of uncertainty in both the arts and politics, Corita Kent’s assertion that “Doing and making are acts of hope” resonates deeply. The Pop Art Nun died in 1986 after a long and prolific career, but her example lives on. To commemorate the center’s opening, the center’s board of directors wrote in a statement that its “new chapter invites everyone to participate in building a world of justice, creativity and possibility, where hope is created through collective action.”

The center’s opening exhibition, on view by appointment, is “Heroes and Sheroes.” It’s the first L.A. exhibition to show that series in its entirety: twenty-nine prints made from 1968 to 1969 honoring historic figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Coretta Scott King, John F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez—people who changed the course of history with their courage, just as Kent bravely changed the world through her practice and her mentorship.

So, who was Corita Kent? A pioneering figure in postwar American art, Kent’s work bridged the worlds of Pop Art, social activism and spiritual reflection. It’s too easy to think of her as a graphic designer—her work was built around typography, with words and phrases in beautiful cursive scripts or blocky fonts—but Kent was an artist who used text as a medium with which to engage with contemporary culture. Her work challenged artistic and societal norms, and her influence extended far beyond the art world—impacting movements for civil rights, anti-war activism and feminist discourse. Her legacy continues to inspire artists, educators and activists around the world, and her prints can be found in the collections of institutions like LACMA, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Met.

In hope (1965), we see the word HOPE, backward, over poet Ned O’Gorman’s words: “The secret is to risk disaster, hope for triumph and describe the forms of the incarnation.” Though Kent’s artworks were made over half a century ago, they still feel relevant in today’s America, for better or for worse.