With a 40% break on what they’d normally owe the city in property tax, the owners of a luxury emporium at 20 Hudson Yards seem to have a good deal. But that hasn’t stopped them from filing appeals against the city claiming that they’re hugely overtaxed.

Over the eight years running through February of the current fiscal year, owners of 60 New York City commercial properties that already received large property tax breaks — mostly in high-profile locales like Hudson Yards, Times Square or downtown Brooklyn — also sought to lower their taxes by challenging the city’s valuation of their holdings. Forty of those properties were awarded assessment cuts totaling nearly $2 billion, city Tax Commission records show.

20 Hudson Yards, a shopping mall for the ultra-wealthy — Tiffany, Cartier, Piaget, Bulgari and Patek-Philippe have glittering stores there — is a prime example. Built by real estate giants Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group, the property, run by a joint venture called ERY Retail Podium, LLC, received a total of $78 million in city property tax breaks from 2020 to 2024, records show. At the same time, the Tax Commission has awarded cuts in the property’s assessed value that total $467 million, which would normally be worth about $50 million in property tax.

Even then, the mall’s owners weren’t satisfied. For six out of the last eight years, they have filed lawsuits challenging decisions of the Tax Commission, an obscure and understaffed city body that hears appeals.

New York State’s constitution gives developers the right to challenge their assessments, and New York City’s lucrative tax break programs do not ask companies to waive their right to challenge their tax assessments in the future.

In contrast, some states want developers that get tax breaks to accept limits on their ability to appeal their assessments as being too high.

New York’s open invitation to appeal assessment reductions chips away at the property-tax dollars that play a vital role in funding city services. Commercial real estate companies usually appeal their assessments annually. Given the opportunity for a second bite at the apple, developers already benefiting from a tax break take it.

“Of course they appeal. It becomes part of the game they’re playing,” said Elizabeth Marcello, an urban policy professor at Hunter College who has studied public authorities. Asked what to do about it, she continued: “Don’t allow the appeals. A tax break is a tax break. There should just be a policy called the `You’re Being Selfish’ policy.”

But Ken Fisher, an attorney who focuses on real estate development and a former City Council member, said it is important to preserve the builders’ right to appeal property valuation because the city Department of Finance’s assessors don’t always get it right. “Hamstringing a developer from being able to have their property accurately assessed, to me, would be unfair and bad public policy,” he said.

‘Partners’ Face Off

Real estate leaders and city and state economic development officials say that but for tax breaks, groundbreaking developments such as Hudson Yards or the Times Square revitalization would not have occurred. City and state agencies grant tax relief to spur what they say are job-producing public-private “partnerships.”

But these partnerships seem to rupture at the courthouse door: When developers don’t get the assessment reductions they want from the city Tax Commission, they generally file suit against that agency and the city Department of Finance in State Supreme Court.

The computer-generated, cookie-cutter lawsuits, filed by a small group of law firms specializing in this area, typically claim shoot-for-the-moon reductions of 50% and even 75% in the assessed valuations. Property owners file hundreds of such lawsuits each year, appealing the Tax Commission’s decisions on their assessment challenges.

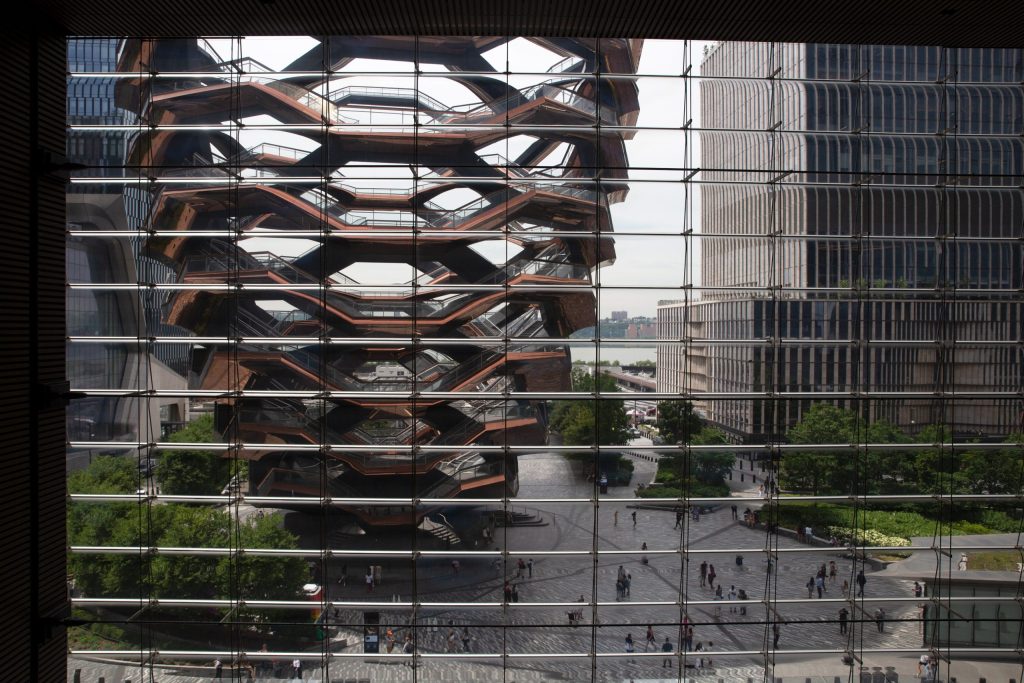

Luxury brands graced the Hudson Yards mall, Nov. 28, 2021. Credit: Leonard Zhukovsky/Shutterstock.com

That’s so for 20 Hudson Yards: ERY Retail Podium is actively pursuing a suit over its 2023 assessment, which it claims should be cut by another three-quarters. The company also filed lawsuits for the current fiscal year and last year, but the cases haven’t gone before a judge yet. (A Related Companies spokesperson declined to comment.)

Nationally, it’s common for restrictions on assessment appeals to be built into subsidy deals when the project is in a tax increment financing district, or TIF, according to David Misky, a Milwaukee official who is chairman of the board of the Council of Development Finance Agencies.

The TIF method — loosely adapted in New York City to finance Hudson Yards — creates a zone in which development is projected to eventually yield increased property values and, therefore, higher property tax revenue. That revenue, instead of getting deposited into the city treasury, goes to pay back bonds that financed construction of the development.

The Bloomberg administration used a TIF-like scheme to jumpstart the construction of Hudson Yards atop a rail yard and to build a subway extension. It exempted commercial properties in the Hudson Yards district from property tax, replacing it with a payment in lieu of taxes, or PILOT, at a discount of up to 40% on what property tax would be. All of this payment would go back into paying for Hudson Yards rather than to the city treasury.

In budget-speak, the foregone revenue is a “tax expenditure,” as much a government expense as, say, the $140 million allotted this year for the Queens Public Library. The difference is that the library money went through a budget process that requires City Council approval.

The tax breaks for developers do not. The quasi-independent city Industrial Development Agency, or IDA, is empowered to issue commercial tax breaks outside the normal budget process, making them a government expense that’s not weighed against other priorities. That’s why budget watchdogs eye tax subsidies closely.

“We strongly recommend that any property that has already received one form of property tax subsidy, including TIF or PILOT, be prohibited from any further abatement or reassessment,” said Greg LeRoy, executive director of Good Jobs First, an advocacy organization that promotes accountability in economic development. “This safeguard is especially critical for city budgets now as the Trump administration imposes federal austerity on states and localities.”

Warren Dubitsky, who heads the Condemnation & Tax Certiorari Committee of the New York City Bar Association, says that such restrictions create problematic risks for developers. He offered a hypothetical of a company that got a 50% tax break, only to see its property assessment doubled. “In that case, the PILOT beneficiary’s right to challenge the assessment is key in making sure that they realize any benefit at all,” he said via email.

Some states have laws that can help protect municipalities against assessment appeals in TIF districts.

Minnesota, for example, allows local governments to set a minimum property assessment, according to Justin Cope, a legislative analyst at Minnesota’s nonpartisan House Research Department. Deals can also be structured in a way that would speed up the reimbursement developers get for their costs if they don’t appeal rising assessments, he said.

The leases granting large tax breaks in Hudson Yards go in the opposite direction by specifying that the developers have a right to appeal their assessments.

“It’s like they almost encouraged them,” said Rachel Weber, a professor of urban planning at Harvard University who has studied the tax breaks at Hudson Yards. A 2022 study she co-authored found that the property tax breaks in Hudson Yards were inflated because city officials based them on a consultant’s erroneous assumptions, as THE CITY has reported. The study said the lower payments in lieu of taxes have brought larger profits for the developers, since offices there fetch the highest rents in the city. At the same time, the study found, properties in Hudson Yards were more likely to have assessment appeals than buildings in comparable areas were.

Of the taxpayer-subsidized buildings THE CITY tracked, 20 Hudson Yards won the most reductions through Tax Commission appeals. Next on the list is One Bryant Park, a 55-story office building on Sixth Avenue, diagonally across from its namesake park.

The Bryant Park owners have scored $296 million in property tax benefits since 2010, according to reports the city’s budget office files with the City Council under a 2005 disclosure law. Even so, One Bryant Park LLC — owned by the Durst Organization and Bank of America — has appealed almost annually to the Tax Commission and filed 13 lawsuits against the city over those years to seek big cuts in its assessed valuation as well.

The company hit the jackpot with its appeal for 2020: The Tax Commission granted a $201 million reduction in the property’s assessed value, nearly a quarter of the “trophy” building’s worth. That valuation equals roughly $21 million in would-be taxes. Meanwhile, One Bryant Park received a $21 million tax break that year under the terms of a deal struck with the Empire State Development Corporation, city records show.

As THE CITY reported in 2023, Times Square office buildings erected in the late 1990s and early 2000s continue to get huge breaks in what their property tax would be. Tax Commission records show that in addition, owners of those taxpayer-subsidized buildings have also been offered deep cuts in their assessed valuations, further reducing tax payments. The Tax Commission agreed to $141 million in assessment reductions between 2018 and 2022 for the 4 Times Square office tower, another Durst Organization office building located down the block from its One Bryant Park. (It’s now called One Five One.)

The 4 Times Square skyscraper, Dec. 8, 2023. Credit: Alex Krales/ THE CITY

The Durst Organization responded in a statement: “One Bryant Park and 4 Times Square were built during times of extreme economic instability in New York City — after 9/11 and the crisis of the late 80s/early 90s — and the buildings contributed to the City’s recovery and growth. Neither project would have moved forward without these tax programs and the City would have lost out on hundreds of millions of dollars, jobs, long-term value creation.”

Boston Properties’ 47-story tower at 7 Times Square was awarded assessment reductions annually from the Tax Commission from fiscal years 2018 to 2022, totaling $177 million, records show.

Likewise, developer Scott Rechler’s RXR company was awarded $112 million in assessment reductions for fiscal years 2018 to 2022 for the office building at 5 Times Square. The PILOT payments were $108 million below normal property tax for those years, city records show. (RXR didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

The nearly vacant 38-story office building — built especially for the headquarters of Ernst & Young (now EY) — is now proposed for a residential conversion, according to the Empire State Development Corporation. The big accounting firm left in 2021 for Brookfield Properties’ brand-new, tax-abated 67-story One Manhattan West in Hudson Yards. It’s a prime example of how city subsidies for trendy new “trophy” offices have led to perilously high vacancy rates at competing office towers.

The 5 Times Square skyscraper, Dec. 8, 2023. Credit: Alex Krales/THE CITY

As a result of this shuffle, a consultant for ESDC concluded, the 20-year-old 5 Times Square is “economically obsolete” because of vacancies in the office market, even though it is in fine physical shape.

The AKRF consulting firm cited data showing that “a major source of office vacancy in Times Square has been public incentives that attracted tenants to Hudson Yards”; it said 1.6 million square feet of office space moved from the city’s crossroads to the former railyard, including law firms Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom and Cravath Swaine & Moore.

And 3 Times Square, a joint venture of the Rudin Organization and Thomson Reuters, was awarded assessment reductions every year but one between the 2018 and 2024 fiscal years, totaling $108 million. As THE CITY reported in the Times Square investigation, the building also continued to make PILOT payments that were tens of millions of dollars below what its property taxes would be, even after half-owner Thomson Reuters reneged in 2017 on its original commitment to make 3 Times Square the company’s North American headquarters.

Overtaxed Commission

While property tax revenue is crucial to the city’s budget, the Tax Commission, which provides an independent forum for assessment challenges, is hard-pressed to keep up with some 57,000 appeals a year with a staff of fewer than 50.

That was clear in a presentation that Neil Schaier, the commission’s president, made at a continuing legal education seminar at New York Law School on Jan. 22.

One of his three top-level supervising assessors had retired early in 2024, and based on “city hiring policy” he hadn’t yet been able to fill the spot, he said. Likewise, he was down two people on his IT staff, and also a clerical associate. He’d been relying on two part-time college assistants to sort and file the 57,000-plus applications, which are submitted on paper, and then pull and re-shelve the paperwork before and after hearings.

Schaier said he lacked the staff to do in-person hearings; they’re all done remotely. (The hearings are closed, and the tax commissioners don’t have public meetings, Schaier said via email.)

He wants to avoid assigning a property to the same assessor each year, but “There are only so many hours that we can devote to the process. We do try.” Schaier later added he was trying to focus on the high-value cases. “We have limited resources,” he said. “This is one area we’re kind of trying to budget.”

The panel’s annual report for the year that ended June 30 says that the Tax Commission handled appeals on properties with an assessed value of $274 billion, 88% of the city’s entire valuation. It makes the understaffed agency something of a sputtering tugboat tasked with pulling an ocean liner into port.

The agency made offers in about 14% of the cases, worth more than $4.6 billion in assessment reductions for that year and $1.5 billion for the previous year. The commercial property challenges — Class 4 buildings, in Finance parlance — were the heaviest load: under half of the appeals, but with nearly two thirds of the assessment reductions.

Those turned away by the Tax Commission have the option of filing suit at State Supreme Court, where the review process starts from scratch. Attorneys in the city Law Department’s Tax and Bankruptcy unit work on defending the city treasury against thousands of assessment challenges per year, according to the agency’s most recent annual report.

A spokesperson said he could not specify how many cases come in, how many settlements are granted or what they amount to. “This is not about a lack of transparency, but quite the opposite,” the spokesperson claimed in an email. “The Law Department is careful not to give out information that could lead to misinformation and misinterpretation. Raw data without the knowledge of the intricate procedures that surround the RPTL [Real Property Tax Law] Article 7 process can easily be taken out of context and misunderstood by the public.”

Our nonprofit newsroom relies on donations from readers to sustain our local reporting and keep it free for all New Yorkers. Donate to THE CITY today.

The post Big Tax Breaks Get Bigger as Mega-Developers Challenge Assessments appeared first on THE CITY – NYC News.