During each of Lollapalooza’s seven years as a touring festival in the ’90s, someone or something inevitably stole the show—sometimes by sheer force, sometimes by dint of controversy, and often by an admixture of the two.

That becomes abundantly clear while reading Richard Bienstock & Tom Beaujour’s zesty new Lollapalooza: The Uncensored Story of Alternative Rock’s Wildest Festival. Speaking with dozens of musicians, agents, promoters, stage workers, and journalists who covered the events in real time, Bienstock and Beaujour—also co-authors of another oral history, Nothin’ But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the ’80s Hard Rock Explosion—have constructed a snappy narrative of the touring festival in its first seven years. (Lollapalooza’s most recent iteration, as a destination fest in Chicago, is relegated here to an outro.)

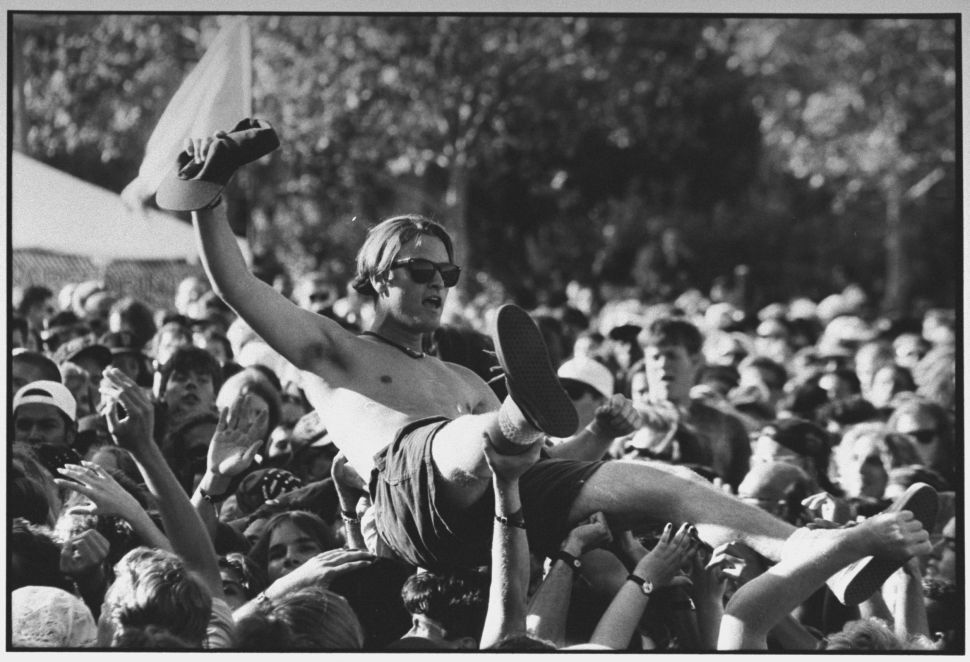

Taking off in the summer of 1991, Lollapalooza was unprecedented—a traveling circus, inspired by the UK and European festivals that founder Perry Ferrell’s band Jane’s Addiction played every year. Pointedly, the U.S. military declined to offer their wares to a youth segment more likely to skateboard and experiment with hallucinogens than not. This was a new counterculture, and Farrell and his festival co-founders, Marc Geiger and Don Muller, had divined that “alternative” wasn’t just a musical direction but accounted for a lifestyle.

As you’d imagine, Bienstock and Beaujour have gathered way more great stories than there’s space to recount here. But here are ten of the best.

Nine Inch Nails out-rocked their tour-mates even with backing tapes.

The biggest act by far to emerge from the festival was Nine Inch Nails, billed fourth out of seven, playing all summer at 5 p.m., in the blazing midday. This was not typically to the advantage of an industrial act. But NIN’s onstage intensity was second to none that year; their T-shirts outsold the Lollapalooza festival shirt itself. People harped on NIN’s use of backing tapes, but nobody who saw them forgot their sheer intensity. “We were absolutely dedicated to total mayhem and anarchy,” says NIN guitarist Richard Patrick. “Trent would tackle me several times during the show. I would throw beers at him, I would throw beers at the audience.” Within a year, Reznor was on the cover of SPIN; in the fall of 1992, the Broken EP would make Billboard’s album-chart Top Ten; and Nine Inch Nails was well on its way to nineties rock royalty.

Pearl Jam, America’s best-selling band, honored their contract and played sixth.

The second Lollapalooza, in 1992, featured the festival’s most legendary lineup: Red Hot Chili Peppers, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Ice Cube—a decade of superstars all in one day. That summer, the Modern Rock format was in the midst of taking over American radio—as David Browne reported in his Sonic Youth biography, more than 100 stations in that format debuted across the U.S. that year. Suddenly, hard rock in skater shorts was everywhere. Sticking to their original contract, made before their debut album Ten took commercial flight, Pearl Jam played sixth out of seven bands on the bill, in the early afternoon, like the good guys they were, right as they were absolutely blanketing radio and MTV. That move paid off for their tour-mates: Because Pearl Jam went on early, the crowds followed suit, and stayed put throughout the day.

Soundgarden’s guitarist met his best friend—in the freak show.

Despite that heavy-hitting musical lineup, most of the Lollapalooza ’92 coverage was given over to Seattleite Jim Rose’s Circus Sideshow, which got many of the mainstage acts to drink bile (most frequent imbiber: Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder) and introduced Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil to his lifelong friend Matt “The Tube” Crowley, whose tube produced said bile. “As a matter of fact,” the famously hirsute and casually dressed Thayil tells the authors, “I ended up being the best man at his wedding.” Mike McCready of Pearl Jam: “That’s hilarious. Oh my god, I wanna see Kim in a tux!”

In 1993, the second-billed band became the real headliner, while the top-billed band became exit music.

Lollapalooza ’93’s headliners were actually Alice in Chains, billed second after people figured out half the audience filed out during the headliner, which this year was the funk-metal cult mutants Primus. “The second-to-end slot is always the coveted slot, but we were like, ‘Screw it. We’re gonna run with it!’,” recalls Les Claypool, Primus’s bassist-singer. The fast-rising grunge-metal Alice in Chains, from Seattle, of course, appreciated them in turn: “Primus played last and they were fucking great,” Alice guitarist Jerry Cantrell attests.

In Philadelphia, Rage Against the Machine got pelted with quarters.

Primus’s Les Claypool tells the authors: “It’s interesting to look at that tour and see that the two lowest-billed bands became two of the biggest bands in the world.” Interesting, but not that surprising, given that Don Muller, the agent who co-founded the festival along with Marc Geiger and Perry Farrell, had his hand in things. “Tool and Rage Against the Machine were Don’s clients,” Marc Geiger says immediately after Claypool’s quote, “and he believed they were going to blow up. And he was right.” Tool went from the second stage to the main stage midway through Lollapalooza ’93, after Babes in Toyland left Lollapalooza to tour Europe; Rage simply blew everyone away. “People were coming in with their hot dogs and their Diet Cokes, settling in for a long day of alternative music,” Rage guitarist Tom Morello says. “And we scared the living shit out of them.” Even Lou Barlow of Sebadoh, the second-stage headliners in ’93 and author of scrappy, nerdy anthems like “Gimme Indie Rock,” was impressed: “I tried to listen to their records after that, and I’m not really a fan of listening to them, like, around my house. But watching them perform was fucking great. They were kind of jaw-droppingly awesome.” The highlight/nadir: Rage’s “protest” performance in Philadelphia, going onstage naked (with socks) while their guitars fed back for fifteen minutes. By the last five, Morello reports, the audience was “throwing quarters at our dicks.”

Nirvana was made a gigantic offer to headline Lollapalooza ’94.

Nirvana’s absence was larger than anyone else’s presence on the 1994 Lollapalooza expedition. The band was supposed to headline this year—Entertainment Weekly even reported it—but the Nirvana contract was canceled that April, mere days before Kurt Cobain’s body was found. The payday, we learn, would have been huge: “Everybody kicks around the idea that we gave Nirvana an offer for ten million,” Don Muller, Lolla’s co-founder, says, letting us read between the lines. “I don’t remember that. I do remember that we knew the economics of the Lollapalooza entity well enough that we knew what a headliner could be paid without really fucking up the ticket prices.”

Perry Farrell didn’t want Green Day to play Lollapalooza because they were a “boy band.”

Including Green Day on the second half of Lollapalooza ’94, opening the entire show at a time when their major-label debut, Dookie, was taking off, was done despite Perry’s push-back: “He was like, ‘They’re a boy band. I don’t want to book a boy band,” the tour’s mid-nineties second-stage manager, John Rubeli, says. Green Day singer-guitarist Billie Joe Armstrong held it against Farrell for years: “I think that made us want to play it even more, actually, because we wanted to prove that he had his head very far up his own ass,” he says. (The two later made peace.)

Somebody threw a shotgun shell onstage during a Hole performance in 1995.

By 1994, Lollapalooza’s branding grew increasingly less edgy—the authors quote Variety typifying that year’s edition as having a “safe, mainstream vibe.” So the promoters elected to make 1995 a much more indie event, musically speaking, starting with the headliners, Sonic Youth, about to release the rangy, jammy Washing Machine, with its 20-minute astral-swirl finale, “The Diamond Sea.” Along with Beck, Pavement, and the Jesus Lizard, they helped make a scrappier, guitar-focused edition that didn’t draw the big numbers of previous years—but made similar headlines for what Pavement’s Scott Kannberg calls “the Courtney Love show.” In the wake of her husband’s suicide, occurring within weeks of her band Hole’s album Live Through This, Love was a tornado on and off the stage, assaulting Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill backstage on the first day out and garnering nearly all of the tour’s mainstream media coverage. In Pittsburgh, Lolla tour director Stuart Ross recalls, “somebody threw a shotgun shell onstage and she saw it,” and Love stopped the show. “I had to make the announcement: ‘I’m sorry, the show’s gonna be a little bit delayed,’” says Ross. “That wasn’t cool.”

Kirk Hammett of Metallica was a Lollapalooza lifer.

If Sonic Youth’s headlining slot shored up Lollapalooza’s credibility in 1995, the 1996 headliner just confused everyone. Metallica—what the hell are they doing there? Well, actually, their guitarist was always there. “I had gone to every single one up to that point,” Kirk Hammett tells the authors. “So it was really disappointing to hear the reaction when we got announced.” But there were significant differences between that band’s audience and the median Lolla crowd, starting with size: “I mean, fuckin’ Metallica took a plane to every show,” says Gary Lee Conner of Screaming Trees, also on Lollapaloooza ’96, along with Soundgarden and the Ramones. That band’s drummer, C.J. Ramone, elaborates: “Metallica had their own tour booked for later that year. So, instead of playing the A and B markets, we were playing the C and D markets in the middle of nowhere.” As for the crowds, Maynard James Keenan of Tool nails it: “There’s a particular crowd that’s going to go see Metallica. And they don’t give a shit about anything else but Metallica.”

There was actually a touring Lollapalooza in 2003.

If this book is missing something, it’s any kind of real engagement with the dance music—or, as the U.S. record biz was then calling it, “electronica”—that dominated the Lollapalooza ’97 lineup: Orbital, The Prodigy, The Orb, and Tricky. But this is a chronicle of alt-rock’s rise and fall, and it keeps its eye on that ball. We learn a lot more about the other insurgent genre that year: the nu-metal of Tool and Korn, the latter of whom dropped out mid-tour. And much as Pearl Jam had done in ’92, Korn’s early set brought out huge crowds in broad daylight. They also augured a shift in radio: “Before Lollapalooza, there were some alternative-rock stations playing Korn, but active rock was really who played us,” says manager Peter Katsis. Opening for Korn were the folky Manchester rockers James, who quickly grew weary of having “Faggots” shouted at them by Korn fans, something that annoyed even Korn’s James “Munky” Shaffer: “They would just be chanting in the middle of James’s set, and it’s like ‘Fuck, dude. Save your energy. Show some respect.’” James’ Tim Booth responded in his own way, by buying “mirror-ball shirts and miniskirts” for the band to play in: “Let’s dress the part and really stir ’em up.” By that point, the U.S. traveling-festival circuit was overwhelmed with choices, from the jam-band H.O.R.D.E. to the femme-centric Liliith Fair to the all-metal Ozzfest. “Lolla had its run,” says co-founder Marc Geiger, “and we knew the model was breaking.” After 1997, Lollapalooza rested for a while—aside from a 2003 tour —before it was reborn as a festival based in Chicago. But, as the authors correctly surmise, that’s another story altogether.