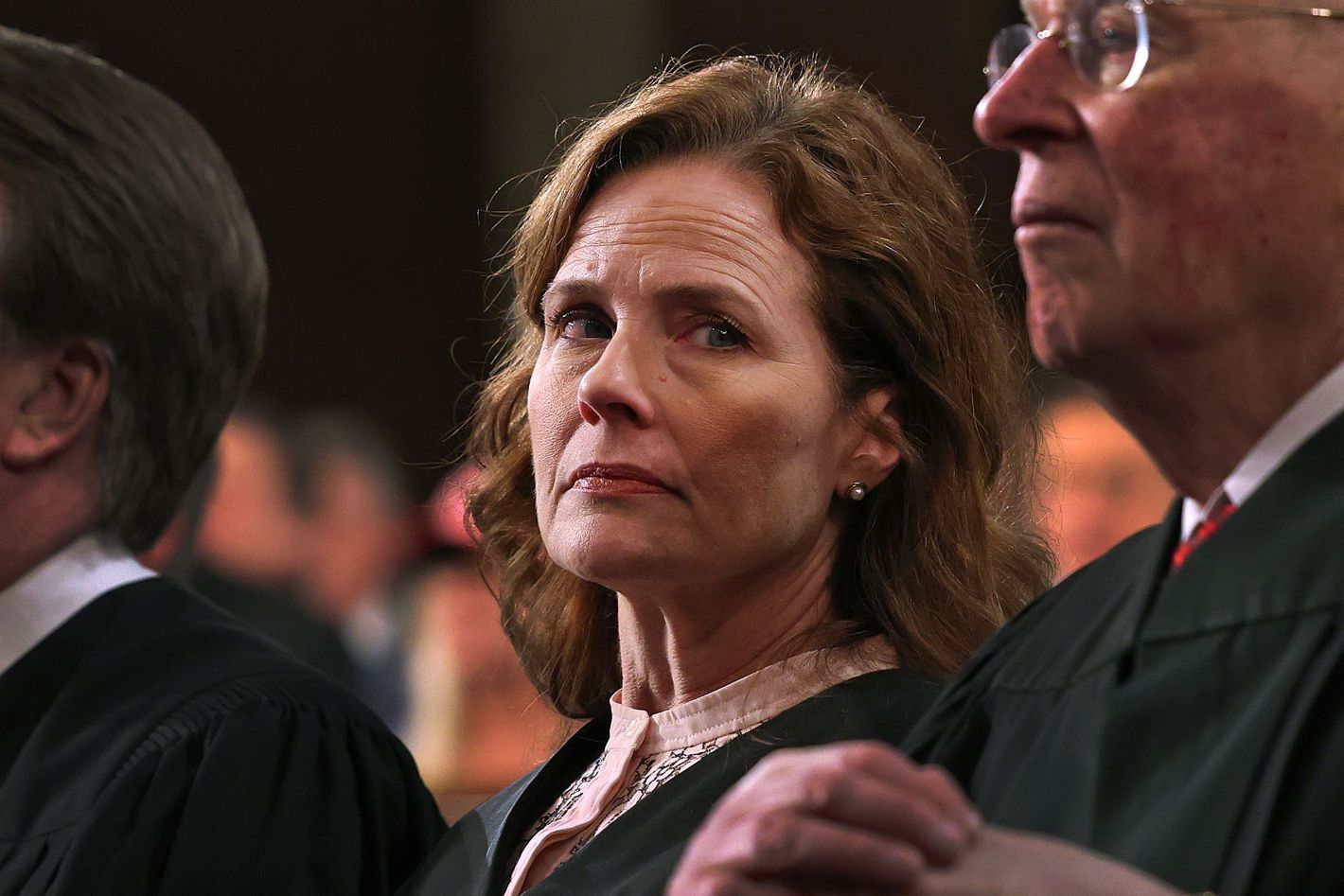

Photo: Win McNamee/Getty Images

Few modern Supreme Court ascensions have felt as baldly predetermined, even scripted, as Amy Coney Barrett’s.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was still alive, and would be for two more years, when Donald Trump started telling people he was “saving” Barrett, then just confirmed to her first judgeship, for Ginsburg’s seat. He waited a whole week after Ginsburg’s death in September 2020 to push through Barrett’s nomination before the presidential election. At her confirmation hearing, there was little attempt to recast Barrett — who had a scant record as a judge but a plain history of ideological commitment — as a caller of balls and strikes. Instead, Republicans sold her to the public with an undisguised mash-up of conservative identity politics and quasi-feminist rhetoric. “All the young conservative women out there,” said Senator Lindsey Graham, then-chairman of the Judiciary Committee, at her nomination hearing, “this hearing, to me, is about a place for you.”

Barrett has, in large part, held up her end of the cynical deal. She provided the lone female vote to overturn Roe v. Wade and helped deliver conservative wins on guns and affirmative action. According to numbers crunched by Adam Feldman on Legalytics, since joining the Court, she’s voted with her fellow Trump appointees around 90 percent of the time. She’s hardly the second coming of, say, Justice John Paul Stevens, a Republican appointee who, by the time of his retirement in 2010, was considered a leader of the Court’s liberal wing.

Barrett has, however, recently shown that she is not a rubber stamp for Trumpism and will occasionally break from the party line if there’s a question of principle or procedural integrity. About a year into her tenure, Feldman wrote, and on a handful of occasions, Barrett did what some of her colleagues hardly ever do — vote with the Court’s center-liberal bloc: “Her willingness to prioritize fairness, clarity, and state autonomy over strict ideological loyalty has led to surprising alignments with the Court’s liberal wing in key cases.” Other court watchers have noticed the trend. “There are glimmers of real independence to her,” says NYU law professor Melissa Murray. Georgetown law professor Stephen Vladeck, who last summer wrote a New York Times op-ed calling Barrett “the most interesting justice” in part because of her willingness to break from the GOP pack, says what’s transpired since has only strengthened the case. Indeed, her incremental moves in the first few months of this year have already been enough to drive the MAGA right to hysterics.

In January, Barrett appeared to join Chief Justice John Roberts and the Democratic appointees in allowing Trump’s sentencing in his hush-money case to move forward, while the other Republican appointees would have granted Trump’s wish to block it. Then, in early March, Barrett wrote a partial dissent in a case involving the Clean Air Act that was joined by all three Democratic appointees. The next day, she and Roberts joined those same liberals to at least slow Trump’s decimation of foreign aid, leaving Samuel Alito to write a sputtering dissent. “Does a single district-court judge who likely lacks jurisdiction have the unchecked power to compel the Government of the United States to pay out (and probably lose forever) 2 billion taxpayer dollars?” he wrote of the abruptly canceled USAID contracts. “The answer to that question should be an emphatic ‘No,’ but a majority of this Court apparently thinks otherwise. I am stunned.”

So, apparently, was the right-wing commentariat. Mike Davis, a former Neil Gorsuch clerk and staffer on the Brett Kavanaugh nomination, told Steve Bannon that Barrett is “a rattled law professor with her head up her ass.” Much was made of a clip of Barrett seeming to grimace at Trump as he walked by her at the joint address to Congress that same week. “She is evil, chosen solely because she checked identity-politics boxes,” raged Mike Cernovich. Laura Loomer called her a DEI hire. Allegations of “evil” aside, there was some technical truth to this; Graham’s chief counsel for nominations wrote that week that Barrett being a woman, being a conservative Catholic, and having a thin record were crucial to getting her through the Senate at a blisteringly quick pace, but he claimed that was “politics” and not DEI.

Though Roberts has previously enraged conservatives with his votes on cases involving the Affordable Care Act and immigration, and Gorsuch and Kavanaugh have broken ranks, “Barrett’s the only one they call a DEI hire,” points out University of Michigan law professor Leah Litman. (Such dismissiveness is already assumed with the justices appointed by Democrats.) Barrett’s true crime, of course, is insufficient fealty to Trump. When law professor Josh Blackman called for her to resign, one of his stated reasons was that “I am fairly confident she does not like President Trump.” A few lone voices on the right, mainly lawyers whose allegiances encompass but aren’t limited to Trump, defended her, including one of the men credited with handpicking her, Leonard Leo — while hastening to add that he agreed with Alito on the USAID case.

It remains to be seen just how far Barrett is willing to stray from the party line. On Friday, Barrett provided the fifth vote to grant the Trump administration’s emergency petition, allowing the government to cancel grants to teachers for supposedly violating the anti-DEI executive order. Roberts, on the other hand, would have allowed the status quo to continue until the case got a full hearing, though he didn’t join the liberals’ bluntly furious dissents.

It was one of a half-dozen cases in which the Supreme Court has been asked by Trump to intervene after lower-court judges uniformly blocked Trump’s rampage through the federal government. The emergency petitions range from challenges to the executive orders on birthright citizenship to the lawfulness of mass-firing federal employees to whether the administration can rely on the Alien Enemies Act to deny due process in deportations. Whether at least five of the conservative justices on the Court agree with their colleagues below or whether they change the rules for Trump will be the true test of the Court itself, and of how far Barrett is willing to diverge from the man who appointed her. For the die-hard Trump crowd, Barrett may pose a genuine threat, says Vladeck: “I think they’re correct to be worried if their only principle is winning.”

There’s more at stake for the Court here than just who wins or loses this round. The administration is betting that it can wield its power in unheard-of ways, even in apparent defiance of lower-court judges. That may be because it assumes five justices will scramble to back Trump’s agenda, but it’s also plausible it doesn’t care what any judges have to say about Trump’s lawlessness. It’s hard to know which scenario is more frightening.

In the meantime, the right might also not be doing itself any favors by antagonizing Barrett. “The ferocity with which the right has turned on her has to stick in her craw,” says Murray. “She was the darling of the right in 2020.” Trump himself arguably showed more political savvy than his flunkies when he told pool reporters, “She’s a very good woman. She’s very smart, and I don’t know about people attacking her, I really don’t know. I think she’s a very good woman.”

That’s the outside game. On the inside, it’s an open question as to how the interpersonal dynamics of the different ideological strands on the right and the center-left will play out. The two furthest-right members of the Court have staked their positions: “We’ve seen increasingly unrestrained rhetoric from Alito and Thomas,” says Vladeck. “We can’t know what that’s doing inside the building, but on paper it seems to be exacerbating the differences between them.”

Meanwhile, both Murray and Litman observed that some of the other justices on both sides of the aisle appear to be more solicitous of Barrett in oral argument. With the current composition of the Court, Barrett rarely has the opportunity to be a swing vote — Feldman identified a total number of six cases out of 30 so far in which she made the difference in the result — but, along with Roberts and occasionally Kavanaugh, can form a bloc of relative moderation. She’s only 53 and has plenty of time to make her mark.

“I’m not chartering the ACB fan club yet,” says Murray. “But I’m watching. I’m interested.” She concedes this could all be the latest Trump-era way for liberals to grasp at straws. “I’d like to believe that there’s some limit to the outright hackishness,” she adds, “but I don’t know if that’s true.”