Illustration: María Jesús Contreras

The original edition of Emily Post’s Etiquette, published in 1922, had little to say about workplaces. Post advised women, who mostly filled secretarial roles at the time, to leave their personal lives at home (“Mood, temper, jealousy … are the chief flaws of the woman in business”) and to not waste much of an employer’s time freshening up. But in a single incisive line, Post distilled the central difficulty of office life: “It takes no small amount of will and self-control,” she wrote, “to get on with any constant companion under the daily friction of an enforced relationship that is unrelieved day after day, week after week.” Basically: Hell is other people.

A century and countless cultural and technological shifts later, American workers generally agree. During the switch to remote work, white-collar employees experienced a measure of illusory relief — excused from the incessant small talk; the expectation to dress a certain way; the optional, but not really optional, happy hours; the smell of someone else’s leftovers in the microwave. Gone was the sensation that they were being observed and assessed based on factors that had nothing to do with their competence.

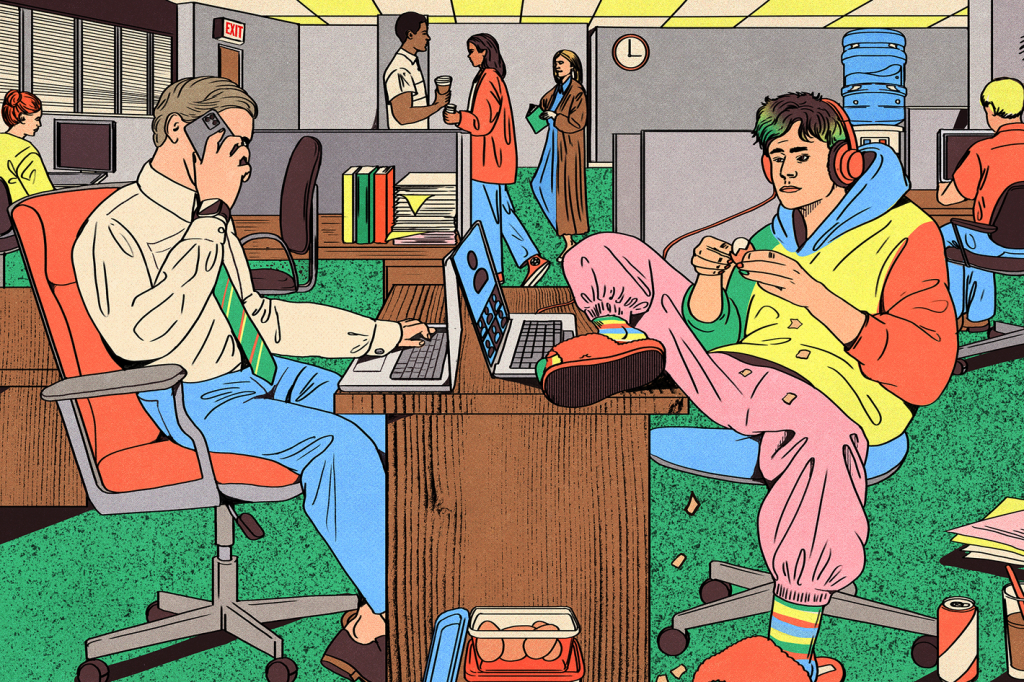

But now, back in the office, these indignities, and endless encounters with the unpleasant physical reality of their colleagues, have returned in full force. Dulled social skills leave us tripping over simple interactions — eye contact is a skill that must be maintained, apparently — and ruminating over minor transgressions. Ever-evolving policies, including hybrid-work arrangements, have scrambled the rule books on basics like hygiene, appropriate working hours, and how to write an email.

Each week seems to bring a fresh instance of egregious workplace behavior — like the woman who developed a habit of signing out-of-office emails for her catering-operations job with “fun little stories about, like, adventures involving squirrels and sharks.” When her boss deemed this unprofessional, she took to TikTok to complain: “I just feel like my personality is being smothered by corporate America right now.” Meanwhile, Gen-Zers, who were never properly indoctrinated in corporate customs before the pandemic (i.e., hazed), are shouldering an outsize portion of the blame: accused of wreaking havoc on office dynamics with outrageous time-off requests, excessive slang, and flagrant disregard for dress codes. (In a segment mocking these generalizations on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert in late April, a young writer for the program, in a micro-miniskirt, advised the audience, “You ghost that office, my lazy kings and queens.”)

The consensus in the media, in the group chat, and by the Popchips in the corporate lounge is that nobody knows how to behave anymore. “Have we forgotten how to work together?” asked Harper’s in its April cover story. Even comedian Nathan Fielder, who loves to flaunt the rules, is interrogating workplace impropriety: The new season of The Rehearsal explores the sometimes lethally awkward dynamics between airplane pilots.

A Great Workplace Reset is in order. Into the gap of this distinctly modern problem steps, from the grave, Emily Post. In mid-May, the institute run by her descendants released Business Etiquette, a thick manual that attempts to translate the doyenne of politesse, and her firm civility, for corporate laborers. Written by Lizzie Post and Daniel Post Senning, two of Emily’s great-great-grandchildren, the book offers practical counsel on how to dress for work, when to send an email versus a text to a co-worker, and how many alcoholic drinks to consume at a work-social event (only one!).

Some of the advice is so rudimentary as to seem mocking of current etiquette illiteracy. An example: Your work calendar should not include “Vasectomy at 4 p.m.” The authors, preoccupied with certain formalities of the past, such as the proper way to knot a tie, can sometimes come across as unconvincing authorities. In their world, a harmonious workplace is achieved through minor choices made minute by minute.

There’s something about fussing over these seemingly superficial details that feels inherently retrograde (never mind all the references to handwritten notes) and anathema to the ambition and passion that is supposed to animate work in our era. For years, the casual workplace has been synonymous with the reasonable workplace. And to question that feels somehow mean or stodgy. But we’ve clearly become too comfortable with our colleagues: Our dirty laundry has entered the office, sometimes literally.

Remote work is partly to blame. Even for those who kept up professional boundaries, years of involuntarily sharing the condition of our couches didn’t help. But the line between work and home began decaying long before the pandemic. As the Silicon Valley start-up sensibility came to dominate corporate office design and culture over the past two decades, a good workplace became the one that most resembled a well-appointed rec room. And the vast sums of money generated in the tech world were proof of concept, for a while.

Now, workers are ready to let the casual office die. My late-30s friends — millennials, who, like Gen-Zers, were once written off as whiners and helped usher in the era of chill work — now yearn for rules. “It’s so off-putting when people take calls from bed,” said a friend who works in big tech. Another, who works in management at a branding agency, lamented the influx of hoodies in the conference room. Yet another noted that one of the most discourteous things a colleague can do is to reply to work emails while technically on vacation — a gesture that muddies the limit between work and play for everyone.

Business Etiquette offers an extremely well-timed path out of the chaos. But reading it, I often felt sharply admonished and sat a bit straighter in my chair, as if being observed by an intimidating headmistress. I was directed at every turn to keep my own side of the street clean. This is useful, sure, but also banal. Conditioned by the me-centric language of self-help, I kept waiting for the pearls of wisdom that would lead me to more money, a promotion, a bigger rolodex of clients. Where were all the reminders of the great success that awaited me if I followed these simple rules? Was etiquette just about courtesy for courtesy’s sake?

A passage on how to deal with an anxious colleague was instructive. Imagine a person who insists on prolonging a project by adding new dimensions and throwing last-minute meetings on the calendar at 6 p.m. to “discuss further.” The Posts say to shut him down politely with no room to waver. “I hear you, and I appreciate knowing how you feel about it,” the script reads. “I’m still confident about moving forward as we discussed.”

Manners, we’re reminded, can in fact function as a battering ram to push through walls of competing needs, ambitions, ideologies, and identities. They can also be the building blocks of tolerance and progressive values: Young people are presented as guides, not enemies, and there’s a surprising volume of consideration for the needs of colleagues with disabilities. Referring to people by their desired pronouns, Business Etiquette implies, is simply an act of civility. Culture-war-y topics like gender dynamics and privilege are reframed in common-sense terms: “Remind yourself that not everyone has had your lived experience.” Etiquette might also, the Posts suggest, guard us against the dehumanizing threat of AI. “We don’t treat one another as worker robots,” they write. “Heck we don’t even advise that you treat robots like robots.” “Saying please and thank you to your A.I. devices,” they add, “is worth the added words.”

As I read, my mind kept flashing to a scene from The Sopranos: An entitled 20-something son of a former mafia don attempts to claim turf that doesn’t belong to him. Tony’s dismissal is brutally elegant: “Those who want respect,” he says, “give respect.” This is what the whole Etiquette enterprise is really about. Bringing respect back to the office means acknowledging that it’s not a stage for self-expression or — everyone hold on to something — an outlet for fulfillment. It’s a site of transaction. And like Tony’s turf, it should be well guarded. You gotta have rules.

Related

Managers Have Won the War on Remote Work. Now Where Does Everybody Sit?