Gala Dalí (1894–1982) had a favorite quote she enjoyed repeating: “If, like me, you are neither a brain nor a beauty, creating is the only antidote to self-betrayal.” For a long time, she was mainly known to mainstream culture as Salvador Dalí’s muse and wife, but she was much more than just a source of inspiration and a life partner. “She could not only spot promise and coax it into bloom, but she also knew how to present it so it would be best understood and most appreciated,” is the appraisal Michèle Gerber Klein offers in her new book, SURREAL: The Extraordinary Life of Gala Dalí, which is both a biography of Gala and a cultural-history compendium. “Beyond the legacy of the great art and impactful literature that she co-created with Paul Éluard, Max Ernst, and Salvador Dalí, this inimitable tripartite talent was Gala’s gift to cultural history.”

The purported muse was a writer, a creator of surrealist objects, a designer and an art dealer who guided and advised her husbands, first French poet Paul Éluard and then the iconic Salvador Dalí. She was a woman among the Surrealists, a friend to René Char and René Crevel, a lover of Max Ernst and a character from Thomas Mann.

Born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova in the Russian city of Kazan in 1894, she relocated to continental Europe in 1912 when she was sent to Davos to recuperate from tuberculosis. At the Clavadel sanatorium, she met the then-17-year-old aspiring poet Eugène Émile Paul Grindel, whose talent she recognized. The encounter prompted him to publish his first poetry collection, Premiers poèmes (1913), under the pseudonym Paul Éluard. His subsequent work, Dialogue des inutiles—a suite of fourteen breezily romantic mock arguments between the poet and his beloved—is introduced by an essay by Gala herself under the pen name Reine de Paleùglnn. Correspondence between the two indicates that she was a thorough editor. The two would end up marrying, having a daughter and eventually becoming involved in several ménages—either as each other’s primary partner or as lovers post-divorce. Even as a young adult, Gala’s star-making ability was evident.

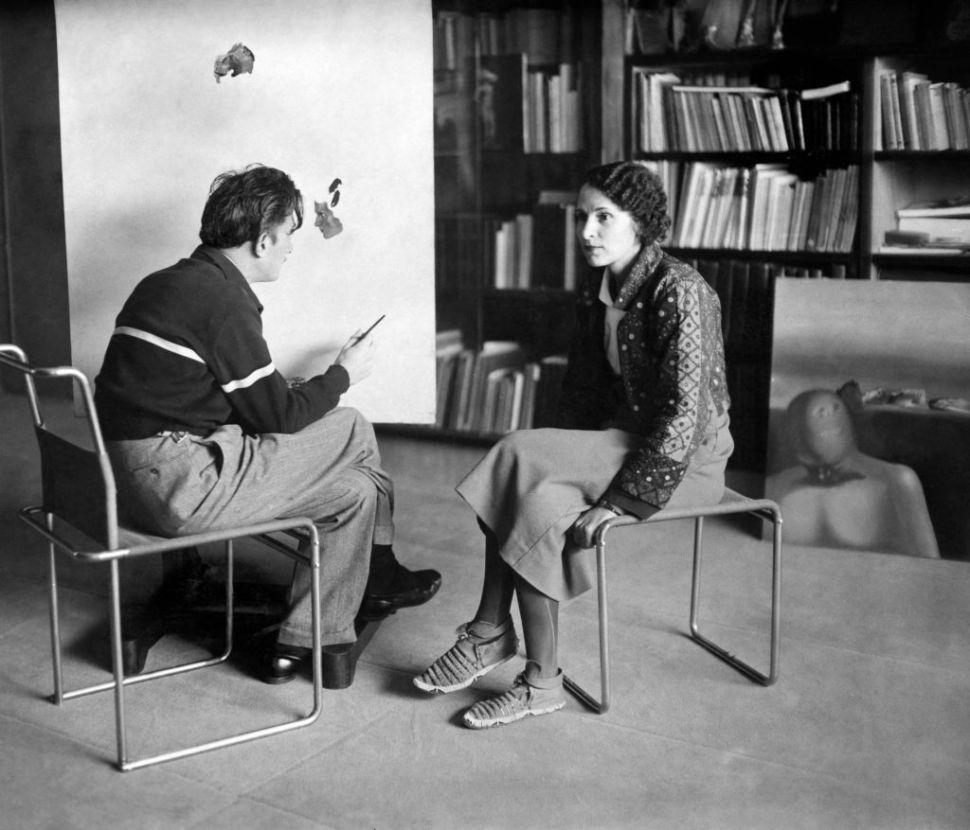

Famously, after meeting her would-be second husband, Salvador, she initially started as his critic and model but became instrumental in creating a real business plan around the work they were making together. She strongly encouraged him to diversify his output, which at some point included objects and book illustrations. “She negotiated and organized Dalí’s exhibition and sales contracts with Pierre Colle, the new gallerist Charles de Noailles had recommended. She also took charge of all matters relating to the presentation of Dalí’s work,” Gerber Klein writes in SURREAL. “Gala became her lover’s ‘life coach.’ According to Salvador, she taught him ‘the principles of reality and proportion; how to dress; how to go downstairs (without falling six times); how to eat (without throwing chicken bones at the ceiling); how to recognize their enemies; and how to stop losing their money.’”

In a draft letter dated 1945, she explained to her stepfather that she handled “everything related to the practical part of [her and Dalí’s] life because he, as you can see, is totally immersed in the creative world, in his work. He is not able to deal with these trifles.” She was able to negotiate $2,500 (equivalent to over $54,000 today) for one advertisement, $5,000 (over $110,000 today) for book illustrations and $600 (over $12,000 today) for a magazine reproduction of one of Salvador’s paintings. “Although she claimed to be ‘not very good’ at practicalities herself, Gala had a Midas touch, and Salvador renamed her ‘Soloizé’: the Russian word for ‘my gold.’”

Other artists she influenced include Max Ernst, whom she guided—alongside Éluard—toward an early version of Surrealism. She also suggested that Ernst sell design objects in addition to paintings. Her guidance was highly sought after, even though she did not dole out flattery. At one point, she offhandedly mentioned to Italo-Argentine painter Leonor Fini that she might “take [her] career in hand” (even as Salvador called Fini “Better than most, perhaps,” before adding that “talent is in the balls”). While Fini refused to take the offer seriously, Gala was nonetheless ecstatic. “She did come alive when she was nurturing young talent and was regularly on the lookout for protégés,” according to SURREAL. One such disciple was Michel Pastore, otherwise known as Pastoret or Little Shepherd. “I believe that Gala was attracted by artists who expressed a very personal vision and combined theatrical personalities with technical ability, independence, and ambition,” Gerber Klein told Observer. “Gala always had close relationships with her protégés.”

She was the mind behind several notable 20th-century innovations in art and design. Most of Dalí’s design inventions actually originate from Ladder of Love, a maquette Gala made in the 1930s for a Surrealist apartment shown at the Surrealist exhibition of 1935. “It naturally led to many famous Dalíean inventions, including the lobster telephone and the lip sofa, which in turn paved the way for expressions of talent in more commercial forms, such as perfume bottles in the shape of noses and ashtrays with rims like coiled serpents,” Gerber Klein said. She was portrayed wearing a lobster as a hat as early as 1934, and the crustacean would feature as a prominent couture piece in Elsa Schiaparelli’s 1937-38 fall-winter collection. She also enlisted Christian Dior—whom she had known since he was just an assistant in the early 1930s—to design her and Dalí’s costumes for Carlos de Beistegui’s Ball of the Century at Palazzo Labia in Venice on September 3, 1951.

In an era where personal branding has become a widespread obsession, Gala’s life story is emblematic of the heights to which it can be taken. “You could say that Gala wrote the book on self-branding—from the chapter on scandalous behavior to the essay on unforgettable appearance and a personality that kept people talking, Gala combined self-promotion with a good deal of knowledge and a very sharp intelligence,” said Gerber Klein. Another strength was versatility; Gala Dalí wrote The Secret Life, which became an international bestseller, and she famously designed store windows with her husband. “She and Dalí were constantly refining their artistic practice to keep pace with whatever decade they lived in… If she were alive now, I am sure Gala would excel at social media.”