It wasn’t the California wildfires that closed down the Underground Museum in Los Angeles; it was grief. In a heartbreaking announcement posted on the museum’s website this past January, the artist Karon Davis, Noah Davis’ wife, explained why her family closed the art space the couple founded in 2012. Her husband passed away from cancer in 2015, Karon’s note explained, and the family needed more time to deal with their pain. The Underground Museum, already sorely missed, was a realization of Noah Davis’ intent. The U.K.’s first retrospective of his artwork, titled simply “Noah Davis” at London’s Barbican Art Gallery, provides a moving insight into the workings of both intent and institution.

A charming film in the exhibition space shows Davis (b. 1983 in Seattle) telling an interviewer how he was born to paint. Following a move to Los Angeles in 2004 after dropping out of New York’s Cooper Union School of Art, his breakthrough as an artist came four years later when long-time supporter and gallery director Lindsay Charlwood included three of his paintings in a group exhibition. Davis was going through a brief dalliance with abstract painting, and there’s a room dedicated to that period—although only one painting survives: a canvas of flat color. His time with abstraction done, Davis returned to the kind of haunting work characterized by 2007’s 40 Acres and a Unicorn. A wry comment on the U.S. government’s promise of land and a mule to slaves granted their freedom in 1865, replacing the paltry and patronizingly-mooted farm animal incentive with a unicorn sums up the quiet irony and elegance in Davis’s paintings.

SEE ALSO: L.A. Museums Are Rethinking the Rules of Art Ownership. Will Others Follow?

The room next door is dedicated to the Underground Museum. Noah and Karon Davis founded the art space in the working-class Arlington Heights district in L.A. with the intention of making high-quality art more accessible to the largely Black and Latinx local community. “I like the idea of bringing a high-end gallery into a place that has no cultural outlets within walking distance,” Noah Davis told Art In America in 2013. However, when the pair approached museums and galleries to ask about borrowing artwork to exhibit in the new space, the response was almost overwhelmingly negative. So they got to work, and an exhibition, “Imitation of Wealth,” presented perfect replicas of artwork by the likes of Jeff Koons, Dan Flavin and Robert Smithson. William Kentridge was more than happy to contribute to the Underground Museum (Kentridge’s film Journey to the Moon is at the Barbican, playing on a loop) and after he got the nod from Kentridge in 2014, Davis commented how ironic—that word again—it was that the first artist to agree to exhibit in a museum created by Black artists was white.

Davis was fascinated by mysticism, and his Gods of the Afterlife 2009 series of paintings reflects his interest in ancient Egyptian religion and mythology. Isis shows a young girl in a dancer’s outfit, delicately lifting her golden wings. Interpreted from a photograph, the figure wrapped in mummy-esque pajamas in 1984 is his wife as a six-year-old child. The economy of the painter’s limited palette here gives his artwork an elusive feeling. The colors used are muted throughout, and Davis didn’t concern himself with details like facial features or the faithful depiction of environments. Instead, paint drips and lollops across his canvases, fading in and out like memories.

Davis’s imagination flicked between paradigms of idealism and society’s hard truths. His 2012 Savage Wilds paintings came from American daytime television’s racist and misogynistic representations of Black people. He would pause recordings of shows like The Jerry Springer Show and Judge Judy and paint what he saw in the frozen frames. The figures he produced are vague, often overweight and somehow hapless.

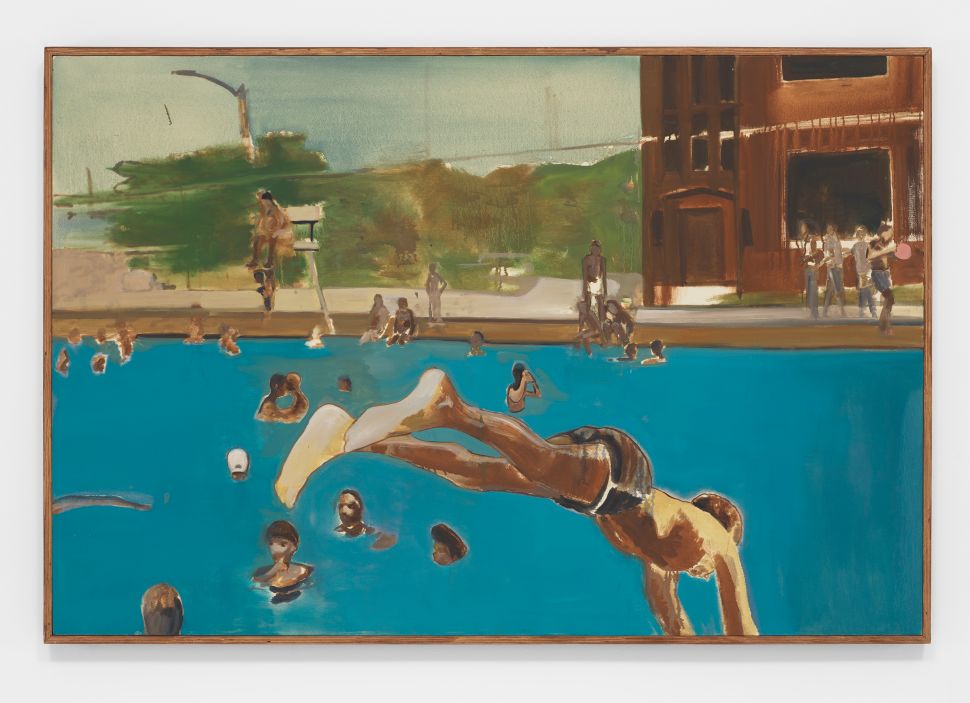

For his 2013 project—in which all pieces are entitled 1975—Davis made paintings based on more family photos. At odds with the synthesized portrayals of folk in Savage Wilds, 1975 is an archive of everyday life that hums with intimacy as people swim, play and go about their business.

The Pueblo del Rio paintings from the following year are based on the 1941 design for a Los Angeles housing project for Black defense workers. Davis imagined how the project could have been, and the artworks embody a calm utopia, replete with white-gloved ballet dancers, musicians and wonderous public sculptures. In reality, the housing project deteriorated into one of L.A.’s most violent and impoverished districts. Around the corner, Seventy Works is a series of 2D mixed media pieces Davis made while undergoing chemotherapy. Some were sold to help his family cover the costs of his medical treatment, while others were given as gifts to friends.

Even as the survey in London is comprehensive, there is so much left unsaid in Noah Davis’ work. Untitled from 2015 was painted three months before he died. A woman and girl lie asleep on a couch, and we view them through an open door. Are we intruding? Are they okay? The effect is disconcerting, and for an artwork to have this kind of impact is a reflection of Davis’s remarkable gift for beginning a story but leaving the plot unresolved. As with the best societal narrators, Davis showed without telling, depicting scenarios that are both troubling and enthralling.

Noah Davis was just thirty-two when he died. We can only hope that his family finds peace and that when they are ready, the Underground Museum will reopen once again.

Noah Davis‘ largest survey to date is on view at the Barbican Centre in London through May 11, 2025. Advanced booking is recommended.