The AIDS crisis looms over vast amounts of queer art. Whether or not it was made in direct response to this moment of human tragedy and political carelessness or not, the AIDS crisis forces us to reconsider the ways in which we might understand the work of any queer artist making work through the 1980s and 1990s; a black hole that threatens to swallow up any other way of understanding the work. Peter Hujar’s vast photographic practice might not have been designed to specifically be a reaction to what was sweeping through his community of friends and contemporaries, but in the wake of it—and Hujar’s own passing due to AIDS-related pneumonia—so much of his work has come to stand as a record of what’s been lost. Some of this is in the portraits of contemporaries who passed away, like David Wojnarowicz and Candy Darling, while some of it is in his images of Christopher Street Pier or ruined buildings in New York’s Soho. Whether we want to or not, we might find ourselves looking at Hujar’s dilapidated landscapes and languid, prone subjects and grieving.

This gesture towards death is what opens “Performance and Portraiture / Italian Journeys,” a retrospective of Hujar’s work at the Luigi Pecci Centre for Contemporary Art; one of the first images is Palermo Catacombs #1 (1963), something that immediately places Hujar’s work under the shadow of death. But more than that, the work in “Performance and Portraiture” reveals how Hujar’s photography so often shows moments of the past and the present bleeding into one another; his portraits of David Brintzenhofe applying makeup before going on stage show a man caught between states of being. Just as the bodies of his subjects might invite us to think about how thin the gap is between life and death is—the veiled Gary Indiana seems to embody this fragility perfectly—and Wojnarowicz’s series Rimbaud in New York, also on display as part of the exhibition, is able to take a figure from the past and place him, a vagabond, into the present, Hujar’s work becomes an archive of people and places that have been lost to time. These photographs give us something material to mourn, not just in the faces of artists who have been lost or in the ruins of piers and New York buildings, but in capturing the beauty of these places. Hujar’s images of young men in Italy, sunbathing on the rocks, or the casual eroticism of the cruising denizens of the Christopher Street Pier show us not only the idea of something lost—in the way that his images of ruined buildings or Italian catacombs do—but exactly what that something was.

SEE ALSO: Painter Catherine Goodman On Abstract Palimpsests and Other Realms of Consciousness

It’s no wonder that “Eyes Open in the Dark,” another Hujar retrospective at Raven Row in London, shows Hujar’s work alongside images of the artist made by his contemporaries, including an almost cubist grid portrait by Paul Thek and images of Hujar on his deathbed taken by Wojnarowicz. Through this artistic communion, Hujar and those in his inner circle are able to provide us with a kind of lineage, a way to place ourselves within a timeline of queer art and artists ruptured by the AIDS crisis. In contrast to this, Hamad Butt, the subject of “Apprehensions,” a retrospective at IMMA in Dublin, moves away from solid and recognizable images of the past. Butt’s work was more explicitly informed by the AIDS crisis and his own diagnosis in 1987; in a video where the artist is interviewed by his younger brother Jamal, Hamad reveals that he was “unable to express what [he] really wanted to say because of the limitations of painting.” While Butt’s work is no less of a document of a time and community ravaged by the AIDS crisis, his work offers a much less material world for us to grieve, instead trying to capture a precarious landscape through more abstract forms or those that foreground Butt’s own proximity to death.

Butt’s work is about language, or rather, the failure of one. Where Hujar offers up understandable visual representations of people and places, Butt seems to be saying that there is no literal, figurative way to respond to the AIDS crisis. Instead, he uses abstraction and metaphor as a way to grieve. In Fly-Piece (1990), the installation that opens the IMMA retrospective, a colony of flies—some living, some dead—goes about the motions of life behind the glass doors of a noticeboard. In each of the three sections of the board are texts that offer up declarations on faith, violence, and the intersections of sex with death in no uncertain terms: “We have the eruption of the Triffid that obscures sex with death,” reads one line of text. The triffid, lifted from John Wyndham’s novel, recurs throughout Butt’s work, a shorthand for the way in which the AIDS crisis is presented in his practice: as something apocalyptic.

Even beyond his installations, the Triffid hovers in the background; in the pastel and pencil drawing No title – Transmission (Triffids and Line of intent), a piece of paper is bookended by drawings of triffids; five in the top left corner and 2 in the bottom-right, at the end of the page. All that exists between them is the Line of Intent, a series of blue dashes moving from one end of the page to the other. The Line might be notches on a bedpost, a tally of the dead, something as simple as the days passing into one another. Butt’s constant return to the alien body of Wyndham’s novel—and the juvenile sexual imagery of his 1990 video Triffids, part of the Transmission installation—offers the bug as a metaphor for the ill body and for the outcome of an AIDS diagnosis. Butt’s work in the wake of his diagnosis is explicit about the possibility of death; his Familiars installation, holding dangerous combinations of chemicals just out of reach from one another, even places the spectator close to death. If Cradle, where chlorine is contained is a Newtonian cradle, is looked at from the right angle, it looks as if the blown glass chemical containers are touching, that the slightest force could shatter them.

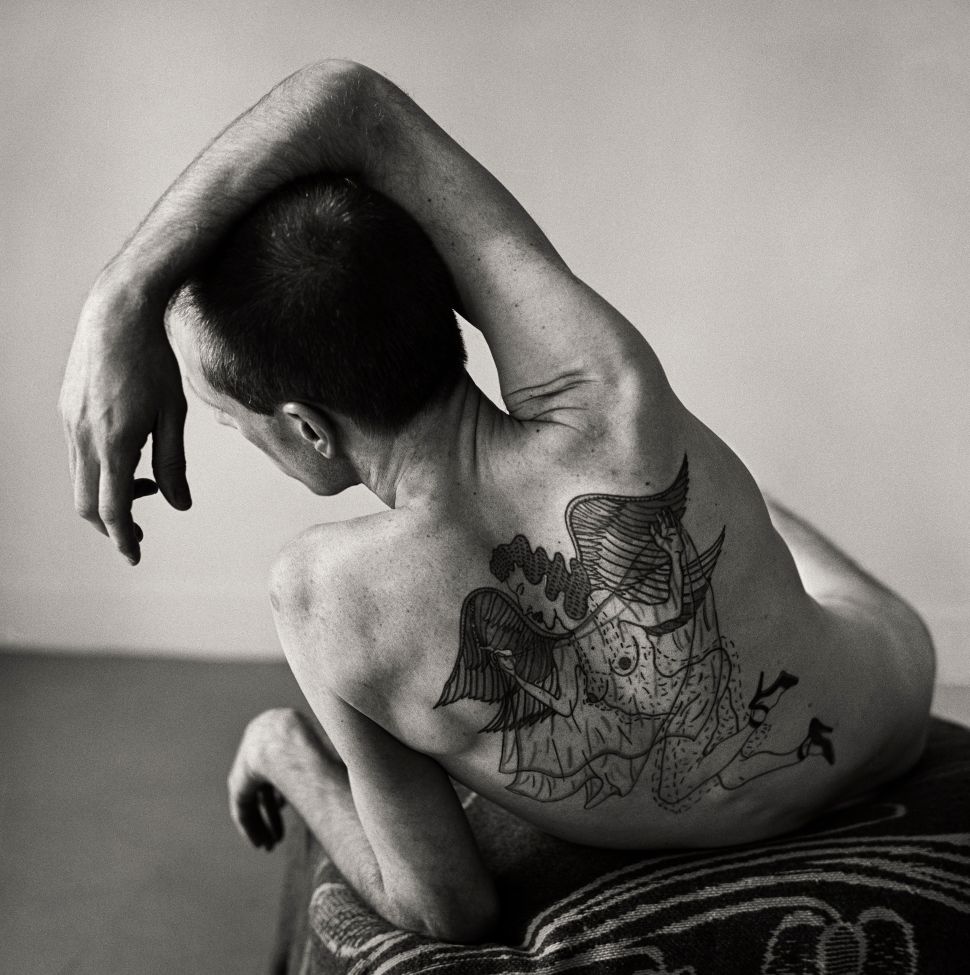

It’s ironic, then, given Butt’s formally oblique art that makes such direct references to death, that even as Hujar’s work is more aesthetically direct, he rarely tackles death itself head-on. Even his images of Palermo’s catacombs feel more about the idea of what’s been lost than the idea of death itself. Of course, one of Hujar’s most famous photographs, Candy Darling on Her Deathbed (1973), presents Candy close to death, but it’s another image, one in the Raven Row retrospective, that offers a different perspective on Hujar’s approach to photographing the end. In Jackie Curtis Dead (1985), Hujar photographs Curtis in his casket, eyes closed for the final time, with a flower on his suit and a disco record at his side. While there’s so often an assumption of mortality within Hujar’s work—the poses of his subjects and the context of the AIDS crisis we’re forced to reckon with his work—the way he presents death itself feels different; there’s a stark finality here that exists at odds with the world that he captured. Hujar captured a world that was so alive; even subjects lying prone or deep in thought like John Waters and Susan Sontag (the former shown as part of “Performance and Portraiture,” the latter in “Eyes Open in the Dark”), are liable to come alive, possessed by some thought or possibility, at any moment. This, inevitably, becomes part of how we grieve a lost community through Hujar’s work; we’re presented with a world of possibilities taken away from us. Instead of capturing the act of losing something, Hujar shows us what’s been lost.

What might bring these artists together isn’t just the way in which, in vastly different visual languages, they show a world that came undone under the shadow of death and plague, but instead, questions of memory: how is it we can remember what’s been lost? Whether intentionally or not, there’s a moment in “Apprehensions” that echoes Hujar’s practice. When Hamad is being interviewed by his brother, he lies on the sofa as if he were posing for a Hujar portrait, offering up a part of himself to us as if it were the easiest thing in the world. Butt’s work understands how fragile and precarious things are, showing them in real-time through ambitious, unsettling installations. It’s these moments, where whatever space there might be between life and death feels so thin that we might be able to glimpse through it if we try hard enough, that Hujar seems to freeze in time. So much of his work is dedicated to the moments of life that are lived in between. This can be seen in his images of performers—Hujar’s images from Italy capture the transience and transformation of live performance like little else—and landscapes; in one of the final rooms of the Raven Row is a series of Hujar’s photos of the Hudson River, the portraits and faces that we so often associate with his work are gone, and we are asked to reckon with the realities of absence and what we can do with the empty spaces left behind.