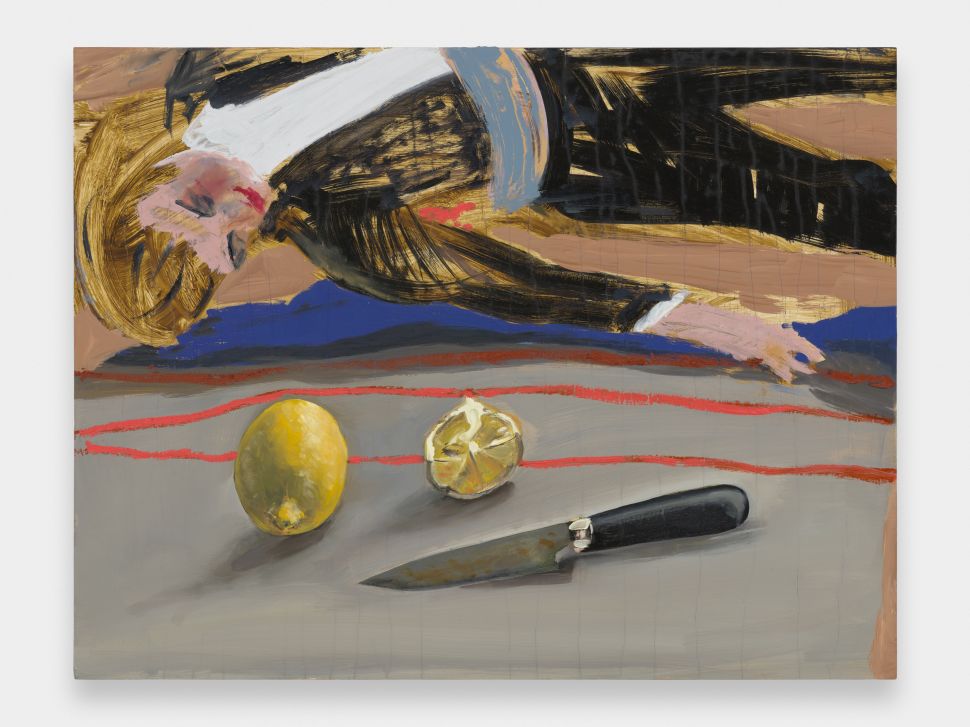

Ella Kruglyanskaya loves lemons. They appear in several of her new paintings on display at the Thomas Dane Gallery in London, but most memorably in Lemondrama (After Manet), in which the foreground is occupied with a sliced and whole lemon next to a knife. The crudely painted dead body lies secondary in the background. Lemon drama, indeed.

Such wry humor runs throughout Kruglyanskaya’s work. Perhaps that’s the key to her success. The Latvian-born artist, now based in Brooklyn, is certainly enjoying a busy year. “Shadows” is the first in a series of three exhibitions of Kruglyanskaya’s work across the year, with the second opening in Basel at Contemporary Fine Arts in June and the third in the autumn in New York at Bortolami Gallery.

SEE ALSO: Noah Davis’ Legacy Lives On in the Barbican’s Poignant Retrospective

Kruglyanskaya has said that she wants her paintings to feel cinematic, to hold suspense, seduction and scenery within the frame. There’s undeniable drama in many of the paintings in “Shadows,” seen most starkly in Everyone and Their Mortality, her sardonic memento mori depicting a skeleton lying among aubergines slithered like slugs (plus half a lemon, but of course). Yet, for all its melodrama, Kruglyanskaya’s work winks at its viewer, showing off its artifice. We’re continually being reminded that we’re looking at a painting. Beneath the aubergines and skeleton, Kruglyanskaya includes a painted ‘How to’ strip at the bottom of the frame. Death isn’t the only thing we’re being reminded of.

Several of the works are dialogues between drawing and painting, another referential twinkle. In Odalisque with Lute and Apples, for instance, the nude woman is a hazy scribble of lines in front of neatly painted apples and a lute, as if the complete work were incomplete. But this interplay between painting and drawing is central to Kruglyanskaya’s practice. Throughout her career, Kruglyanskaya has ruminated on the role of the artist and the role of women in particular. In Odalisque, the female nude raises questions about the history of women represented purely as objects of male desire, with Kruglyanskaya’s signature wit.

Plenty of other elements reinforce this self-awareness, such as the painted hole punches at the edge of Roots with Signature (featuring root vegetables, not lemons). The edge of Odalisque likewise has strips of paint as though accidentally borrowed from the wall on which it hangs.

But the best examples of Kruglyanskaya’s self-awareness are the exhibition’s titular shadows. In paintings Adventure (in Gray) and Shadows, Kruglyanskaya paints over her drawings with bold lines of shade, as if the frame were hanging by a nearby window. Indeed, these grey strokes depict the long shadows cast by the light entering Kruglyanskaya’s New York studio. Painting usually depicts light as it falls on subjects; these works depict light as it falls on canvas.

Kruglyanskaya made a name for herself through her bawdy work, with past exhibitions presenting cartoonish faces and bold colors. Here, there’s greater delicacy, if not subtlety, in “Shadows.” Many of the canvases explore shadows, but all of them are self-aware. Ignoring even Roots with Signature—the signature taking up the entire bottom of the painting, in duo-toned curves more attractive than the ostensible subjects of the vegetables—Kruglyanskaya’s presence is unignorable throughout the exhibition. We look at not at drawings but her drawings; not at light but her light. The bold lines aren’t just shadows. They are Kruglyanskaya’s shadows as she sees them.

“Ella Kruglyanskaya: Shadows” is at Thomas Dane Gallery until May 3, 2025.