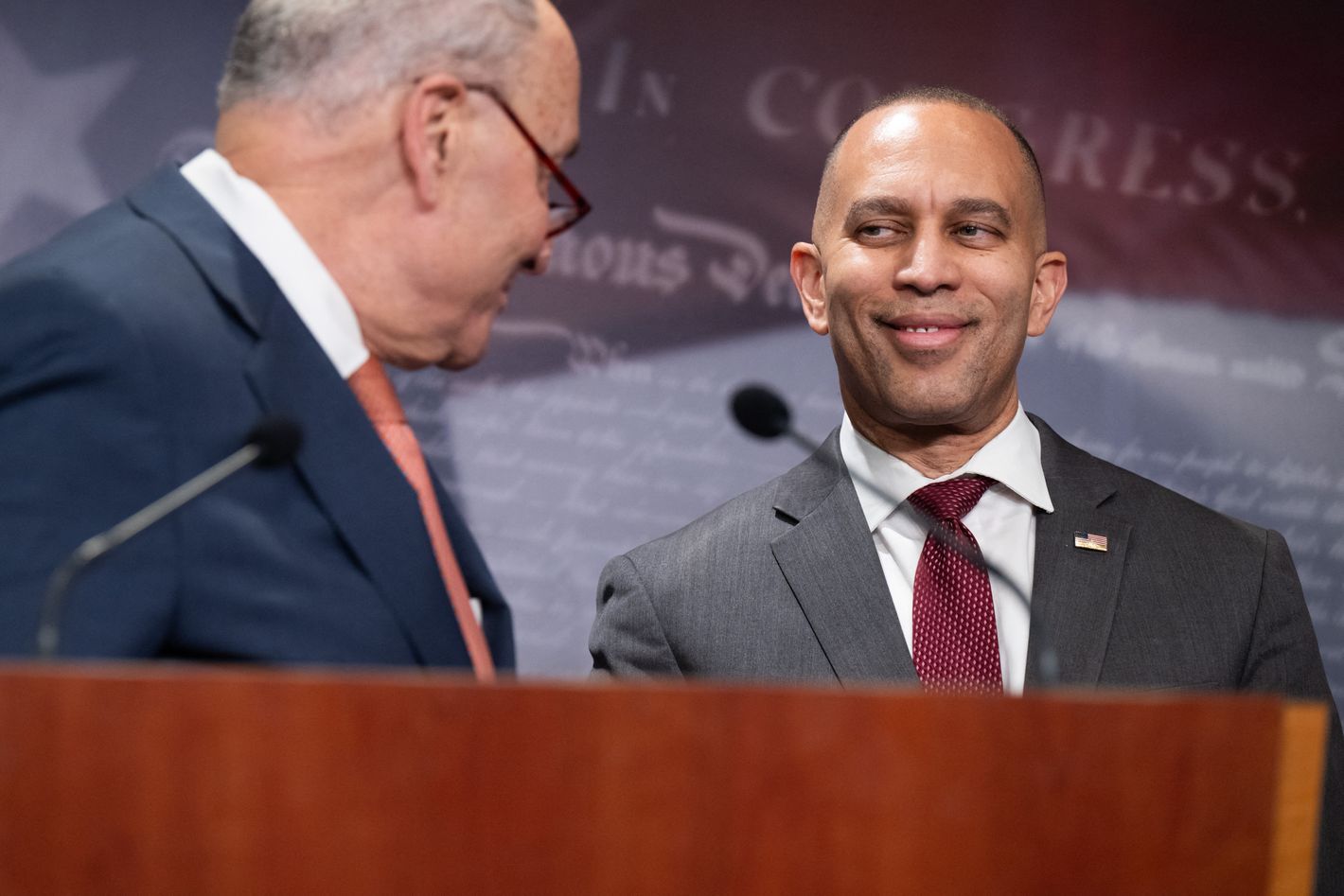

Photo: Saul Loeb/AFP

A few weeks into Donald Trump’s second term, a MAGA-supporting acquaintance asked me why the left seemed “so unbelievably demoralized.” He was not (merely) gloating; he was curious. “I’m sure it won’t last,” he told me, “but for now it’s just sort of a bewildering sensation to feel like you’re doing politics with no opposition.” There was a note of pity in his voice.

He wasn’t wrong. The first signs of life from the dazed Democrats following the inauguration were not exactly encouraging: Joining a protest outside the Treasury on February 4, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer held hands with California representative Maxine Waters — an icon of the resistance to Trump’s first term — and chanted “We will win!” several times before seeming to realize the implausibility of his boast. Interrupting himself, he leaned into the mic and rephrased: “We won’t rest! We won’t rest!”

Shortly after, House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries waved the white flag. Smug, offended, and baffled all at once, he asked reporters, “What leverage do we have? Republicans have repeatedly lectured America: They control the House, the Senate, and the presidency. It’s their government.” As if we hadn’t noticed.

Rarely inspiring, party leaders are selected for their capacity to find consensus, manipulate parliamentary machinery, and fundraise. Ask anyone why Jeffries is minority leader: He brings home the bacon. Schumer once had a salty, outer-borough pique that did some work to counter Trump, but his mien today is weary and distracted. In the middle of a January presser charging the president with having “plunged the country into chaos,” Schumer turned his attention to his ringing cell phone, then told the crowd that his grandson had lost a tooth. “It’s a very big occasion,” he said.

But the lethargy has deeper roots. Chastened by Trump’s victory, Democrats seem to lack the courage of their convictions, if they even know what those convictions are. Politically and literally geriatric, they keep doddering into rooms and forgetting why they were heading there in the first place. The fierce cultural politics that defined the party in Trump’s first term are out of favor. Biden’s pro-labor populism didn’t work. The liberals are sidelined; the ascendant moderates offer warmed-over Clintonism and Cold War nostalgia. The base wants more spirited dissent, but cautious electeds fear being associated with disruption. (The various spectacles during Trump’s speech to Congress — Al Green’s sincerity notwithstanding — felt both anachronistic and vaguely embarrassing.) All that marching around is a flavor of “woke.” And wokeness, they say, cost them the election.

Like many political losers before him, Jeffries is indulging in the blithe comfort of not being responsible. If the Democrats are powerless to stop Trump, he reasons, they can’t be blamed for the consequences. And maybe, when the real pain starts, the public will pine once again for the party of order, the adults in the room. On February 25, James Carville made this logic explicit in a New York Times op-ed: “It’s time for Democrats to embark on the most daring political maneuver in the history of our party: roll over and play dead. Allow the Republicans to crumble beneath their own weight and make the American people miss us.” Sounding very much like a divorced parent desperate to win back our affection from “fun dad,” Carville wrote, “Just when they’ve pushed themselves to the brink and it appears they could collapse the global economy, come in and save the day.”

It is a particularly liberal delusion that a party should be rewarded for its powerlessness. If it were ever plausible, Trump has put that notion to rest. Power must be met with power. As political currency, responsibility and competence have lost their value. (Blame inflation.) Dad gave the kids too much candy, but the sugar high may never wear off.

At least two Democratic senators seem to understand this new reality: Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Chris Murphy of Connecticut. Both are contesting Trump’s status as the sole protagonist in D.C. and articulating a more urgent vision for the opposition. Sanders landed the first blow against Carville’s rope-a-dope scheme. “The problem is the Democrats have been playing dead for too many years,” he said on Meet the Press, citing bleak markers of inequality and poverty. “I don’t think you play dead. I think you stand up for the working class of this country.”

Sanders has taken this message — the same one he’s been peddling for 50 years — on the road with his Fighting Oligarchy tour, holding rallies in swing districts with Republican incumbents in the hopes of pressuring them to vote against cuts to Medicaid and other services. The energy of these events, his staff said, significantly exceeds what they saw in the fall when Sanders was campaigning for Kamala Harris. As the senator told me via email, “Trumpism will not be defeated inside the D.C. beltway.”

Murphy, in a phone call, was more generous toward leadership’s perspective, describing its theory of power, in which it is reserved and opportunistically released, as “traditional.” But ultimately, he said, the past ten years were a victory for a different model, one in which “power is a muscle, and if you use it every day, your message is not hurt by repetition and by constant volume. It is helped.” If Democrats don’t exercise that muscle, Trump is left to do what he does best: monopolize our every waking moment. What’s more, Murphy suggested, Democrats imperil their credibility if they don’t treat Trump’s threats with alarm. “You lack sincerity if you said during the campaign that if voters elected him, he was going to destroy democracy, and then once he gets sworn in, you’re not acting as if it’s a moment of existential crisis,” he said.

Murphy’s sense of crisis, like my own, has been cultivated by exposure to the ideas of the “new right.” During the Biden years, he undertook a study of MAGA’s more florid intellectual currents. The movement he saw “was tapped into the spiritual emotional crisis that the country was going through in a way the left wasn’t and was planning for 2025,” he said. It was “deeply radicalized” and motivated by an overwhelming enmity. If Murphy was quicker than most Democrats to recognize the “existential” danger of Trump 2.0, it’s because he knew it would be this movement running the show. “They don’t really think that democracy has much use any longer,” he said.

Murphy’s actual message, however, is similar to Sanders’s. Murphy may be concerned about what new-right intellectuals like Michael Anton or Darren Beattie are doing in the White House (both are State Department advisers), but most Americans don’t care. “Right now, we have to be laser focused on telling people the story of what’s going on,” Murphy said. “It’s the kleptocratic billionaire takeover of our government that can only occur by the destruction of our democracy.”

Defending democracy, as such, didn’t much profit Biden or Harris. Democracy can feel like an abstraction — or worse, when it fails to provide. But if Democrats don’t take the threat seriously, they risk not only their credibility but the means to contest for power in the future. Their trouble is that they’re undergoing an identity crisis — reimagining how to build an electoral majority — while needing to protect our constitutional order and vital services from psychopathic billionaire arsonists and con men. They’re driving the ambulance and repainting it at the same time. It’s not an easy task. But a populist message that names the enemies, and links them to the public’s deprivation, is a good start.

I sometimes think the reason Democrats are so despised is that everyone across the political spectrum, whether they know it or not, has high expectations for the party. (Some weird, unconscious hangover from New Deal hegemony, perhaps.) Republicans expect them to be good-faith opponents, moderates expect them to be pragmatic, liberals expect them to be ardent champions of rights, and the left and labor expect them to be sincere egalitarians. The Democrats are barely any of these things now. They could be again, but they’ll have to learn: In American politics, you win or you lose. Righteous defeat gets you nowhere. There is no dignity dividend.

Related

A New, Moderate Way Forward for the Democratic PartyThe Lessons From 2024 Democrats Really Need Right Now