Acquisitions are an integral part of a collecting museum. Not only because the museum will act as a safekeeper for generations, but also because these acquisitions are wind vanes for the museum’s mission and vision. As such, any exhibition presenting recent acquisitions is a barometer for the contemporary zeitgeist of an institution—an apt description of the exhibition “Vivid: A Fresh Take,” now on view at the Hunter Museum of American Art.

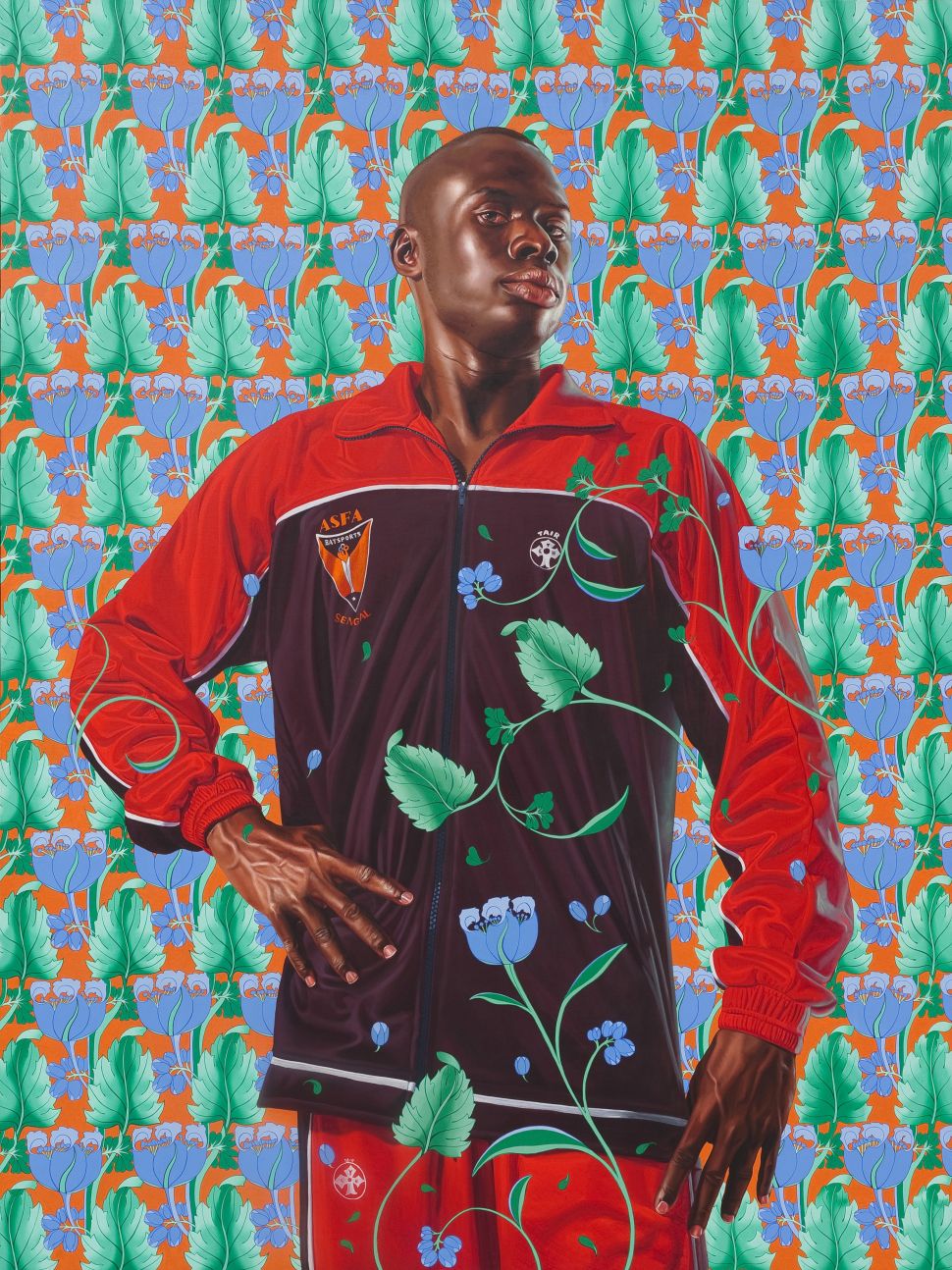

This exhibition is full to the brim with work by exceptional artists—Kehinde Wiley, Bisa Butler, Toyin Ojih Odutola and Sanford Biggers are among the names represented. “‘Vivid’ offers a fresh look at lost or overlooked histories and stories,” reads the exhibition text. “Each artist whose work is featured in the gallery interrupts established narratives by provoking reflection about history and perspective.”

This fresh look is seen most evidently in Harlem Youth, Harlem, NY, August 1964 (1964) by Larry Fink. The black and white photograph captures a close-knit group of Black women on a stoop—one sitting, the rest standing, one smoking a cigarette, all gazing obliquely away from the camera or with their eyes downcast and wearing emotionally apathetic expressions on their faces. This melancholic congregation of sisterhood, situated among a slew of other photographs by Fink from similar years documenting civil rights protests, not only disrupts the fiery, impassioned scenes of struggle seen in Fink’s other photographs but also disrupts the perception of civil rights protests as equally fierce endeavors. As much as the civil rights movement was about legal liberties and freedoms and equal treatment under the law for all races, it was also about the right for Black people to exist mundanely, unbothered by others.

Sadly, this is where the success of the curatorial endeavor begins and ends. While other works in the show support some part of the curatorial thesis, Fink’s photography is the only selection that fits within the conceptual parameters.

Kehinde Wiley’s Ferdinand-Philippe-Louis-Charles-Henri, Duc d’Oléans (2014), a painting of a Black man in contemporary streetwear against a Rococo-inspired patterned ground, does well to interrupt established narratives but hardly counts as an overlooked history as it is precisely the anachronistic juxtaposition of elements that make Wiley’s painting powerful. Similarly, Toyin Ojih Odutola’s drawing Prompt (2021-22), a portrait of a Black woman resting her head in her hands, celebrates the beauty of Black people in leisure, but this can hardly be called a lost story as Larry Fink’s photograph from sixty years earlier presents the same subject.

Elsewhere, there are inclusions that seem to be complete anomalies—notable among them is Family Album Series: I (2013) by Daud Akhriev. The painting depicts a trio of formally dressed figures floating in a swirling ground of scrawled gestures and shapes. The inclusion of a formal Russian family portrait, no matter how stylized, was jarring and inexplicable. How does this artwork provide a fresh take on history? In the next room stands Susan Walked In (1976) by Christopher Wilmarth. A large minimalist sculpture of steel plates and a pane of glass, it’s a time capsule of the minimalist art movement of the 1970s. Its utter lack of deviation from the Western understanding of minimalist sculpture of the time prompts one to ask, once again, how the work interrupts an established narrative.

Posing these questions against the ground that they are museum acquisitions, by extension, contests the intention of the museum’s collection. Is the museum truly intent on finding niche areas of interruption and fresh perspectives? Or is it simply buying cachet from established or celebrity artists in the hope that the viewer will figure out the “freshness” on their own?

As a museum dedicated to American art, this exhibition shows that the institution’s mission is unwavering, and indeed, there is a wealth of artistic value to explore in the United States. But this particular exhibition fails to present any meaningful disruptions to our current understanding of American art. In its most generous reading, this exhibition shows that contributions to American art have come from numerous sources over the centuries, and those contributions are worthy of collecting. Less generously, this exhibition allusively restates platitudes we have heard ad nauseam for the sake of co-opting the hard-fought prestige held by these artists.

“Vivid: A Fresh Take” is on view at the Hunter Museum of American Art through June 1, 2025.