The first free Muslim settler in Manhattan, Anthony Jansen Van Salee, landed in 1633.

Six years later, the Dutch and North African rabble-rouser, who’d become one of the largest landowners in what was then New Amsterdam, was banished to the hinterlands of Brooklyn for a litany of colorful misdeeds, including paying wages with a dead goat.

Van Salee was the son of a Dutch privateer who’d converted to the faith after he was captured by Barbary pirates and joined their ranks and whose descendants came to include New York City royalty like the Vanderbilts and the Whitneys. His saga is just one of many intriguing stories that history-seekers encounter on 32-year-old Asad Dandia’s tour of a neighborhood in the Financial District that was once known as LIttle Syria.

A historian and Southern Brooklyn native, Dandia successfully sued the NYPD in 2013, when he was an undergraduate at Kingsborough Community College, for surveillance targeting Muslim New Yorkers like him. He now leads the walking tour company New York Narratives.

Dandia is also a prominent online supporter of Zohran Mamdani, the 33-year-old socialist Assemblymember hoping to be elected the city’s first Muslim mayor.

On a recent Tuesday, Dandia guided nearly a dozen Columbia and Barnard students through the canyons of lower Manhattan.

Little Syria was the nickname of the tenement neighborhood on Battery Place, between Washington Street and Greenwich Street, that flourished between 1880 and 1940, until New York City “power broker” Robert Moses used eminent domain to demolish immigrant homes and businesses to make way for the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel.

An archival photo shows Little Syria in 1940 before it was destroyed to make way for the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. Credit: Couresty of New York Narratives

It’s a story that perhaps began with Van Salee.

“Though he was a Muslim, he was not particularly pious. In fact, he was a major troublemaker,” Dandia told tourgoers. “And I’m pulling out my phone because I actually have to enumerate his crimes on my phone.”

The list includes stealing wood from his neighbors, paying off wages he owed with a dead goat and allowing his dog to kill a neighbor’s hog. Van Salee, known informally as “Anthony the Turk” although he was not Turkish, also pointed a gun at an overseer of the West India Company, which captured and sold enslaved Africans. He also captured and threatened a debt collector with bloodshed for seeking money owed.

Not to be outdone, Van Salee’s first wife, Grietje Reyniers, accused the wife of the colony’s religious leader of being a prostitute — a profession she had some reputed familiarity with herself — and disloyal to her husband.

“Now, that’s not something you say at any point to anyone, but in the 1600s in a colony of 1,500 people where social codes are much more different, it’s a major crime,” said Dandia.

Van Salee and his wife were tried in court, and he pled guilty but refused to recant any accusations or repay any debts.

So “they banished him to a far away land called Brooklyn,” said Dandia, drawing laughter from the students.

Living in Coney Island, Van Salee accumulated 200 acres of farmland in what’s not Brooklyn. Much later, he returned to New York City, as it was renamed after the British took control, to buy property on Stone Street near where he’d lived before his exile.

“The thing that I think stands out about Anthony and Zohran is that they’re both cosmopolitans and come from a cosmopolitan background, which makes them both quintessential New Yorkers in a way,” Dandia, the son of Pakistani immigrants who works as an educator at the Museum of the City of New York and as adjunct professor teaching New York City history at Guttman Community College in Midtown Manhattan, said in a subsequent phone call.

Mamdani is the son of filmmaker Mira Nair, whose catalogue includes Mississippi Masala, a 1991 movie starring Denzel Washington that explores interracial romance between Black and Indian Americans, and Indian-born Ugandan author and professor of sociology and political science at Columbia University, Mahmood Mamdani.

The elder Mamdani’s scholarly work and activism took him all over the world, meaning that Zohran had his own peripatetic upbringing, centuries after Van Salee the pirate’s son went on to become the first Muslim to own property in New York.

Walls and Statues

Dandia begins his Little Syria tour, one of several he offers, near the Whitehall Terminal for the Staten Island Ferry, showing students a map of New Amsterdam, which the Dutch established after seizing control of the territory from the Lenape tribes in 1624.

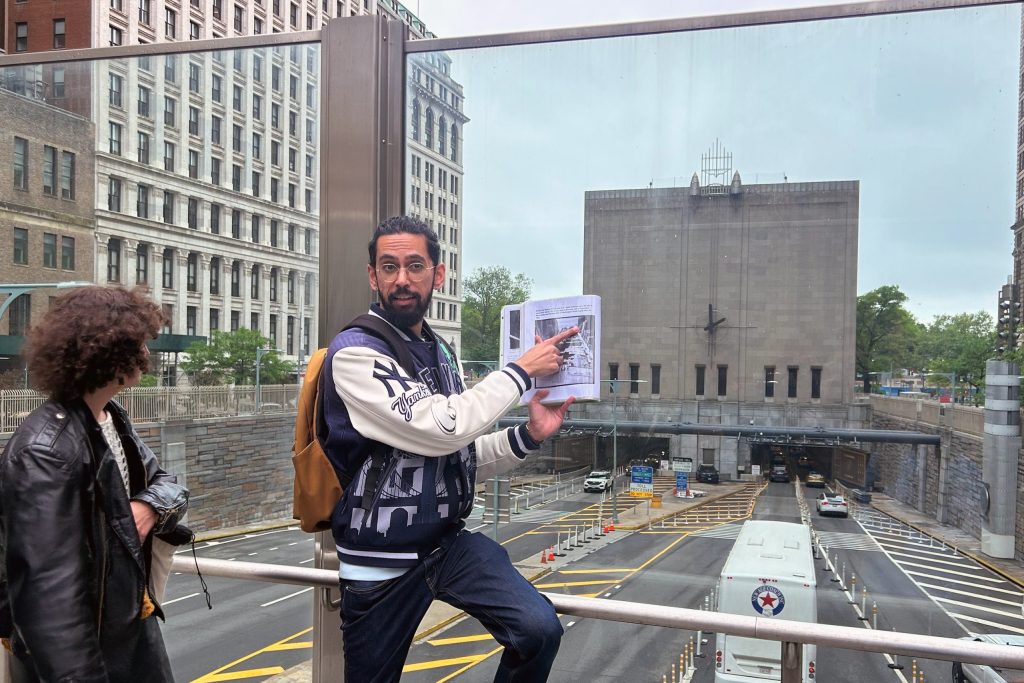

Asad Dandia gives a tour of where Little Syria existed before it was demolished to make way for the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel in Lower Manhattan, May 6, 2025. Credit: Jonathan Custodio/THE CITY

“They erect this colony of about 1,500 people, and what they do is that they fortify it with a huge wall. This is a wall that they used to block off the Indigenous from retaking the land, but also to block off their European competitors, particularly the British,” pointing to a location on the map that today would represent a strip of Wall Street. “That wall gets torn down, and today we call it Wall Street.”

Dandia takes tourgoers through several highlights that include Fraunces Tauvern on Broad Street and Pearl Street where Washington planned the American Revolution, Bowling Green – the backyard of Little Syria. He also recounts that an early variation of theStatue of Liberty was originally conceived as a gift for the Ottoman Empire, to be placed in the Suez Canal shining its light toward the East.

While waves of immigrants came to New York City from Ireland and Germany in the 1840s, the first wave of Arabs didn’t arrive until the 1880s. A decline in the silk industry, farming challenges, ethnic and religious tensions with Ottoman rulers and recruitment from U.S. missionary schools all contributed to the Arab migration, according to Dandia.

An archival newspaper story focused on then-bustling Little Syria at the southern tip of Manhattan. Credit: Via New York Public Library Digital Archive

Mostly of Christian faith, they migrated from the Levant, a region on the eastern Mediterranean shores that included Historic Palestine (which includes Israel today), Lebanon and Syria, according to Dandia. Today, that area would be Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Palestine and Jordan.

They began to set up storefronts and lived in settlements along Washington Street, sharing the community with Irish, German and Eastern European immigrants.

An archival photograph shows a Syrian woman entering the United States through Ellis Island. Credit: Courtesy of New York Narratives

Syrian merchants pitched their businesses on the west side of Washington Street, the main street of Little Syria, since it was closer to the southern waterfront that drove commerce and trade.

They were “merchants, peddlers, people who engaged in commerce and trade,” said Dandia, noting a big emphasis on textiles that included lingerie, suspenders and kimonos.

One of those merchants, Abraham Sahadi, ended up founding Sahadi’s in 1895, the now famous Middle Eastern grocery and eatery that eventually became a staple on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, after the city tore down Little Syria.

Another, Najeeb Arbeely, founded the Star of America in 1892, the first Arabic language newspaper in the U.S., on Pearl Street near Fraunces Tavern. Originally from Damascus, Arbeely and his family were among the original settlers in Little Syria, arriving there after joining missionary school in Knoxville, Tennessee.

The Arbeely family were considered to be among the first to migrate to Little Syria, after first moving to a missionary school in Knoxville, Tennessee that recruited Arabs from the Middle East. Credit: Courtsy of New York Narratives

There were factories in Little Syria for those less inclined to entrepreneurship, but at least one didn’t allow Syrians.

“Babbitt’s Soap Factory was an Irish soap factory that did not employ Syrians,” said Dandia.

Residents, including the merchants, largely lived on the east side of Washington Street in settlements that lacked heating.

Women layered up, “not necessarily for religious purposes, but because it was really cold and they didn’t have heating so they had to wear many, many layers,” said Dandia. “It was not good. A lot of them really struggled.”

Neither struggle nor success survived in Little Syria after its demolition in 1942 to make way for the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel.

“You could say the 40s were the end of Little Syria as a residential neighborhood,” Dandia told the students while facing the tunnel, noting that some residents clinging to the neighborhood were given just 24-hour notices to vacate their homes.

Many of its residents ended up relocating to Atlantic Avenue, which remains a bustling center of Arab commerce.

“Now think about the major Arab communities in New York City. So, the two that come to my mind are Astoria and Bay Ridge, right? What trains take you there?” Dandia asked students during the tour. “It’s the R. It’s the R line that took the community from here to where they are now.”

Arab residents also boarded the ferry to get to their new neighborhoods, Dandia notes.

The past, Dandia’s tours make clear, inform the present in ways worth remembering. In 1776, he notes on the Little Syria tour, then General George Washington called on U.S. troops and New York City residents to topple a statue of England’s King George in Bowling Green.

Dandia compares that to recent efforts to remove Confederate monuments across the country.

“Taking down statues might be the most American thing,” he said. “Washington decided that King George does not represent his ideals. He took it down.”

And, Dandia said, “when we decide that the contradictions of America’s founding do not represent our ideals… we can take down statues of people who represent them.”

Our nonprofit newsroom relies on donations from readers to sustain our local reporting and keep it free for all New Yorkers. Donate to THE CITY today.

The post The Little Syria Tour Guide Bridging NYC’s First Muslim Settler and Mayoral Hopeful Zohran Mamdani appeared first on THE CITY – NYC News.