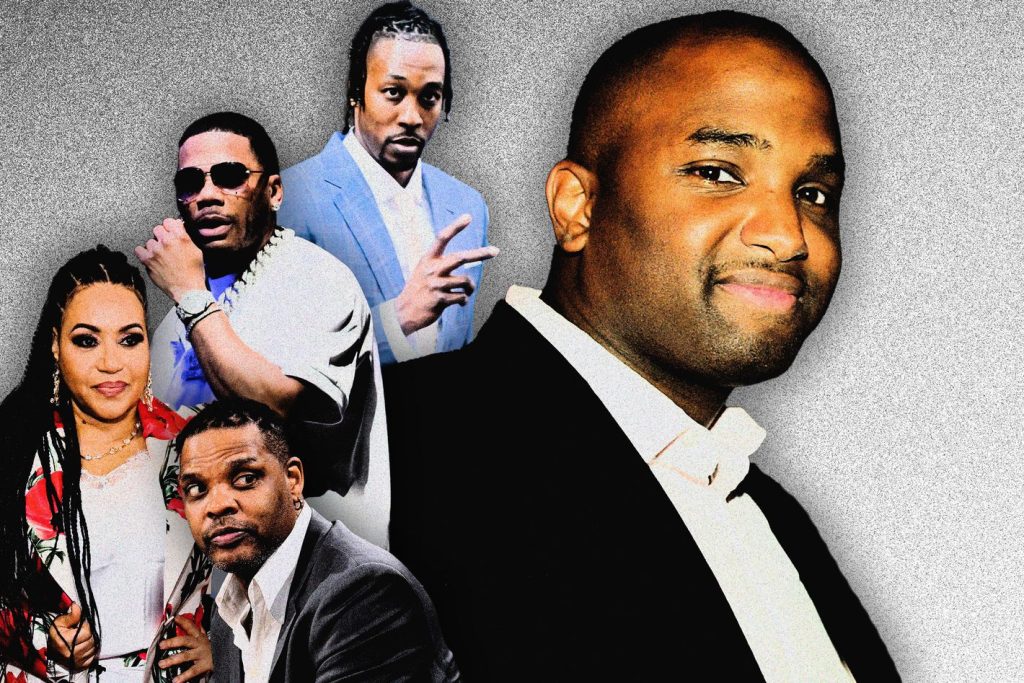

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Photos: Getty Images

Calvin Darden Jr. was living it up in New York City and other people were paying for it. It was the early 2000s and Darden, a graduate of Howard University, was rising as a broker in top financial institutions like Salomon Brothers, Merrill Lynch, and Wachovia. He had an apartment on Wall Street and an uncanny ability to make business deals and get close to celebrities.

“I was trying to hook him up with my sister because he was a young entrepreneur,” said Cheryl James, the Salt in Salt-N-Pepa. He was also friends with Star Jones’s boyfriend, a broker at Merrill Lynch who helped him gain access to star-studded weddings and the business that followed. He knew publicists who connected him with big names in the NBA. He was six-foot-three and knew how to work a room.

“He was charming,” said Mystik Dasilva. “He had a great personality. He was fun.”

Dasilva, working as a dancer at Goldfingers in Queens, met Darden Jr. in the late ’90s at a club in Manhattan and the two started dating. “You could tell that he came from money,” she said. Darden Jr.’s father, Calvin Sr., had risen from the loading dock to become a senior vice-president at UPS, all the way into positions on the board of Coca-Cola and Target. In 1999, when UPS went public, he and his executive colleagues became millionaires many times over — giving his son a ready-made group of clients to solicit.

Dasilva asked Darden if he could help her with her earnings. “I had a lot of cash that was under my mattress and I needed it to not be under my mattress,” she said. “I was like, ‘You make money. You’re smart. What do I do?’” Darden told her to invest her life savings of around $100,000 with him.

His Rolodex of celebrity investors was Entourage worthy: Nelly, Angela Bassett, New York Knicks legend Latrell Sprewell. He moved from Wall Street to a seven-bathroom mansion near the water in Glen Cove, more Mar-a-Lago than Long Island. “There was an actual shark tank,” said Dasilva. The tank cost $210,000 and, as the New York Times noted in 2005, he fed salmon fillets to the black-tip reef sharks that lived in it.

Unfortunately, the financial institutions that gave him six-figure sums upfront on joining found they were not reaping benefits. Wachovia said that Darden only delivered $423 in commissions in his first six months at the bank, far less than his seven-figure goal. More seriously, the bank claimed that he had forged documents suggesting his assets under management were far greater than they seemed.

His celebrity investors also found something was very wrong.

“The money was supposed to come back on a certain day,” said Cheryl “Salt” James. “And on this day I went to check and something in my spirit was like, It’s not going to be there. You just got jacked. And when I went to look, it wasn’t there.” Her investment, which she recalled was $500,000, was gone. In hindsight, she said, the interest he was offering was “ridiculous” and she has since learned to perform “due diligence” since people are trying to scam celebs like her “all the time.”

In 2004, Darden faced larceny and fraud charges in state court in New York. Prosecutors said he pocketed around $6 million from his investors and employers and spent it on exotic fish, furniture, and luxury cars that he drove poorly. (One story in King magazine claimed his license had been suspended or revoked 17 times by that point.) When earlier investors tried to pull their money out, prosecutors said he gave them a runaround of excuses before cutting off contact. Sometimes he would take new money to pay back the people banging on his door. Sources involved in the investigation told the Times back then that a $3 million loan from the Canadian mutual-fund company AIC went in part to pay back James. A $300,000 investment from Latrell Sprewell went to pay off a woman named Catherine Aldridge. She was 87 years old when Darden Jr. ripped her off.

“I would like the people I hurt in this case to know how truly sorry I am,” Darden said at sentencing, following his guilty plea on a grand-larceny charge. He was not sorry enough to quit doing it.

With his friends, Darden Jr. usually went by Ramarro, his middle name. “Until it was business,” said Dasilva. “Then it was Calvin Darden.”

There were many reasons for Calvin Darden Jr. to admire his father, a self-made millionaire, family man, and deacon at his church in Georgia. (Attempts to reach Darden Sr. by phone and by email were unsuccessful.) Darden Jr. said they talked on the phone almost every day. When Jr. was first arrested, his dad put up the collateral for his $1 million bail. When he got out in 2008 after three and a half years, he said his father gave him a couple hundred thousand dollars to get on his feet. While he was in prison the year before, he married a woman named Suhaine Pedroso, who was working then at a Sephora in Atlanta. He had two young kids from previous relationships and would soon have a daughter with his wife. “I don’t like jail and won’t go back for any amount of money,” Darden Jr. wrote his father in an email in 2012.

Before he went to prison, Darden Jr. relied on his father for his client list and good name in business. After getting out, he began taking more liberties with that name. Prosecutors later claimed that included sending emails from an account he made pretending to be his dad, pursuing clients as father and son until he either fumbled the deal or took the money.

Sometimes the father was left holding the bag. In 2011, a “Darden Sr.” got paid to set up a nonexistent Floyd Mayweather boxing match, and it was Darden Sr. who got sued for running off with the money.

The same year, ESPN reported that a “Calvin Darden” had somehow managed to convince the National Basketball Association to let them plan an international exhibition tour; stars who had purportedly signed contracts included Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, and Dwight Howard.

Getty Images

The news articles promoting the tour were enough to convince an investor in Taiwan named Melvin Yen that the Dardens had the weight to bring the New York Knicks to Taipei for an exhibition game. Yen, whose business is bringing top-dollar concert tours to Asia, thought he was mostly in contact with Darden Sr. for the Knicks deal, which Yen recalled as costing $500,000. Darden Sr. even invited Yen to come to New York to meet Knicks owner James Dolan and watch a game with him in a VIP box at Madison Square Garden.

In April 2012, after wiring over a $200,000 deposit, Yen flew to New York to meet Darden Sr. But when he landed in the States, Darden Sr. told him that he was sick and could not fly up from Atlanta. His son would be there instead.

“It was the first time I met Calvin Darden Jr. in person, and his accent was completely different from that of the person I spoke with during the dozens of international calls,” Yen wrote via text. “He was a good-looking Black man, well-dressed, and drove a luxury vehicle.”

Darden Jr. explained to Yen that they couldn’t meet Dolan that trip — his dad’s request came in too late and they wouldn’t be able to get pass to get into the VIP suite. Instead, they had some drinks and apps at a W Hotel he was staying at in the city. “We chatted about the future collaborations for two hours,” he said. “It was a great meeting actually.”

Soon after the trip, their correspondence slowed, with the Dardens disappearing for a month in the fall. Darden Jr. said his father was seriously ill and that he would be taking over the deal. Things fell apart. Yen said that, by mid-2013, he had gone bankrupt from losing the $500,000 in cash flow, creating a “chain reaction” that he claimed left him $17 million in debt. Prosecutors later said Darden Jr. bought a Porsche with Yen’s money and spent a few thousand at a place called Westchester Puppies.

“I didn’t get any funds back,” Yen wrote me. “If I had the chance to see them in the States, I’d want to feed them bullets like Luigi Mangione did to Brian Thompson.”

“Dad, I am not trying to take advantage of you and I am not lying to you,” Darden Jr. wrote to his father. He was trying to convince his father to co-sign a loan because he did not have the credit.

“I don’t ever tell you the whole story,” he wrote. “I don’t want you involved on any level nor do I want you to have any knowledge of anything.”

It was around July 2013 and the private-equity company Cerberus Capital Management was looking to sell the lad mag Maxim. Darden Jr. set up meetings in which he, his father, and an attorney would pitch Cerberus on buying the magazine for $31 million.

Darden Sr. was actually involved this time, coming on in an advisory capacity to help lend some legitimacy to the deal. Darden Jr. then ran with that involvement, impersonating his father in a since-retracted interview in The Wall Street Journal. To his investors, he went a lot further in the pursuit of becoming his father. He bought a second phone line with an Atlanta area code to impersonate his dad in texts and calls. On email and in forged signatures, he took a middle-schooler’s approach that he thought could limit his father’s legal exposure: adding an invented middle initial to his father’s name.

As they pursued the Maxim deal, the Dardens went on vacation together at a resort on Paradise Island in the Bahamas. Darden Jr. snuck away with his Atlanta-area-code cell to send a personal guarantee to attorneys in the other party. He forged his father’s signature, putting him on the hook for the full $31 million if they could not secure financing for the purchase.

By November, Darden Jr. needed more cash to buy time from Cerberus to put the deal together; through the broker Forefront, he found a lender named Mark Weinberg. “What I’m known for is being able to fund deals very quickly,” Weinberg told me. “I use my own money so I don’t have to get approvals from banks.” Weinberg was willing to provide around $5 million as long as Darden Sr. put up collateral.

“They got signed very quickly,” Weinberg said. “Of course, I was dealing with the wrong Calvin Darden.”

On November 12, Weinberg hopped on a plane from New Jersey to California, when he was trying to decide if he should buy the Wi-Fi or enjoy the flight. “I paid for the Wi-Fi,” he said. “Thank goodness I did.” Weinberg says he saw an email sent from his own account saying that he had authorized the release of his $5 million, even though the collateral never appeared. “It was spoofed,” he said. “It didn’t come from me.” Weinberg was furious, stuck at cruising altitude for hours. He asked the flight attendant if he could use the plane’s phone; she asked if it was an emergency. “I said, ‘Well, it’s a financial emergency.’ And she said, ‘No, you can’t.’” Instead, he emailed his assistant explaining the crisis, and as soon as he landed, called the Secret Service, who contacted the FBI.

The next week, Darden Sr. had enough with his son, telling his lawyer he no longer wanted to be part of the Maxim deal. The two would not speak for two months.

Finally being at odds with his father, even while receiving the attention of the Feds, didn’t prevent Darden Jr. from pursuing another line of credit. Forefront then connected Darden Jr. with Shane McMahon, the wrestling-empire scion and son of the current Education secretary, who would offer $20 million to secure the Maxim deal.

Darden Jr. went into overdrive. He spoofed emails from his father, from former Atlanta mayor Shirley Franklin, and from the CFO of Target in order to show that his father was interested and could secure the loan.

As McMahon’s team grew skeptical of Darden Sr.’s reluctance to meet in person, Darden Jr. also impersonated his father’s oncologist in order to provide some excuse to McMahon for why Darden Sr. could not meet in New York. He flew to Atlanta to forge and notarize a physician’s affidavit to convince McMahon that his father was in the hospital. (Darden Sr. was treated for cancer around this time but was not in the hospital.)

In February 2014, Darden Jr. was charged in federal court in New York with wire fraud. He pleaded guilty and agreed to cooperate in exchange for a year in prison. He said he had impersonated his father in emails and text for years.

At sentencing, Darden Jr. apologized again, admitting to the Maxim fraud that “tore my family apart.” He said was “trying my best to kind of put it back together.”

That was the last anyone heard of him for a while.

On July 7, 2020, Dwight Howard was in a hotel room in Disney World thinking about his future. It was the NBA’s COVID season, when the basketball league pulled off a miracle with its self-contained “bubble” on the Disney megacomplex, where stars could do little but eat, compete, and watch TV in isolation. Howard, then 34, was an aging six-foot-ten star relegated to a supporting role on the Los Angeles Lakers, chasing a last shot at a championship ring.

That night, watching ESPN, he saw what could be his next career step: owning a team in the Women’s National Basketball Association.

Kelly Loeffler, then the co-owner of the Atlanta Dream and the junior senator from Georgia, was facing pressure to sell the team for objecting to players wearing Black Lives Matter shirts. In a letter to the WNBA earlier that day, she wrote that the movement promoted “destruction across the country.”

Howard texted his agent about the opportunity to buy the Dream on the cheap: “It’s going to be a fire sale,” he wrote.

His agent had a great idea to finance the deal. He texted back: “Call me bro, I got to tell you this. I just got off with Cal.”

He knew Darden Jr. from another deal and they began courting the WNBA together with a $7 million offer. Howard would provide the money, Darden Jr. and the agent would broker the deal, and Darden Sr. — apparently eager to help his son right his reputation — would serve as the public leader of a Black ownership group that could mark a turnaround following the bad press with Loeffler.

The team wasn’t fully onboard. Howard was still an active player in the NBA, which is the largest owner of the WNBA, and the league prohibits active players from owning franchises. They also were worried about Darden Jr.’s past. Finally, someone had looked him up.

But Darden Jr. wasn’t ready to let this one go. In his late 40s, it was maybe his last shot to have a business that wasn’t scamming rich people. “Hey bro, I’m not sure you understand just how big of an opportunity this Atlanta Dream deal can be for us,” Darden Jr. texted Howard’s agent. “We need to keep this deal alive with Dwight by any means.”

He told the team that Darden Sr. was leading their bid and made up a handsome pitch deck with made-up brand partners including Naomi Osaka and Tyler Perry. To Howard, he signaled that everything was on track. By December, Howard had wired Darden Jr. the $7 million.

A couple months later, Howard turned on ESPN again to learn that the Dream had been sold to a group of real-estate investors from Boston. He was furious. And no one could get Darden Jr. on the phone.

Prosecutors said the Dwight Howard money went a long way. A down payment on a house outside Atlanta where a scene in Bad Boys: Ride or Die and a Teyana Taylor music video were filmed; a $100,000 Steinway piano; tens of thousands in jewelry; a pair of six-figure Basquiat prints. One of the Basquiats is still visible in the home’s listing, along with a Robert Indiana rip-off that reads “Dope.” He stocked the garage with a $285,000 Porsche Turbo and a $341,000 Lamborghini Aventador. He had kept up his aquatic taste over the years, though he modestly went for a $20,000 koi pond in the yard this time.

But one of the first things Darden Jr. did with the money — just six days after he received the first multimillion-dollar payment from Howard — was to write a $20,000 check to Mystik Dasilva for “loan repayment.”

Dasilva had never been able to shake Calvin Darden Jr. He would appear unannounced at a bar she was working at or try to come over to hand her a few hundred dollars at a time. “He showed up and he was wearing a Rolex,” she said, of when she saw him after his first prison stint. “I would get checks for a demeaning amount of money, $3 or $5. So how was he wearing a Rolex?” Still, she had to pick up the phone when he called: “He knew I would answer because I was desperate for the money.”

In late 2020, they met up in front of her apartment in Queens, where Darden, in a Mercedes G-wagon, handed over the $20,000. “I was like, Is this check going to bounce? Am I going to go to jail for this?” she said. It cleared.

For the third time, Darden Jr. did not get away with it. He was convicted in federal court in New York in October 2024 on multiple fraud and money-laundering counts, including for his scheme to defraud Dwight Howard of $7 million. Prosecutors said that Darden had lied over and over about his father’s level of involvement in the deal.

“I don’t want to say they condone it, but I don’t know that the family has really turned their back on him in the way they should have,” said Dasilva.

Despite knowing of his son’s business practices — and despite being sued over and over again himself for these practices — Darden Sr. had again been in his corner for the Dream purchase, the biggest deal of his son’s career. Was he a victim? Or an enabler? Why not both? Now, according to a letter from Darden Jr.’s attorney, Darden Sr. is ill with both cancer and dementia.

Earlier this month, Darden Jr. was sentenced to 12 years in federal prison. If he serves this third prison sentence in full, he will be 62 when he is released. “I don’t know where it came from, but he has this obsession with some form of status and money,” said Dasilva. “I feel like if he gets out, he’ll do it again.”

Seen from the outside, Darden Jr.’s life could seem like an appealing fantasy, grifting celebrities for decades and spending their money on the stuff he wanted. At sentencing, prosecutors argued for the longest term possible. To make their case, fairly or not, they brought up not just his previous convictions for financial crimes, but also an array of arrests that had never led to a conviction. There was shoplifting in 1994; simple battery in 1996; simple assault against an ex-girlfriend in 2002; a contempt-of-court charge for violating a restraining order against the same woman; driving with a suspended license in 2022. They painted a picture not of a swindler’s high-end dream, but of a mercenary career criminal.

They also said Darden Jr. violated the terms of his release prior to sentencing by trying to buy a $4.5 million house in Atlanta. In December, he showed up to tour the home in a Ferrari; his wife came separately in a Lamborghini. The Feds said Darden Jr. reached out to a mortgage broker about the property. The broker told them that he was under the impression that the man interested in the house was Calvin Darden Sr.