John Filmanowicz

Last October, William Banks posted on Instagram that he was looking for a subletter: $1,025 a month for eight months in a prewar building in Crown Heights with three roommates. It’s the kind of message that many New Yorkers put out, hoping to cover their rent during an arts residency or a luxurious season of travel.

His trip would not be so glamorous. “I’m leaving New York for a little while because unfortunately I have to go to jail in Connecticut,” Banks told everyone.

Banks had been arrested at the end of 2023 in Westport — a wealthy town halfway to New Haven from Brooklyn — for stealing five Israeli lawn flags, which residents had planted to show support for Israel after the October 7 attacks. He was in Connecticut visiting his fiancée’s parents for the holidays, and he felt compelled to do something after watching the ensuing attacks on Gaza. “I have obsessive-compulsive disorder, and I got in my head that I should throw these signs away,” Banks said. “I thought that Israel was being very bad and that no one else is going to do it except for me.”

Banks went out flag-snatching in full daylight, dumping them in a trash can that he rolled down the street behind him. Neighbors snapped a picture and scared him off with a threat to call the police.

But when the police arrived, Banks went back for more. He drove up to one residence in his fiancée’s white Prius and stole a replacement flag, driving off as the officer on the scene yelled at him to stop.

“I wanted to get caught — not at the top of my head, but I think deep down it’s like I wanted a point to get made: to make it clear that there are people out there who think that this is fucked up,” he said. The action was not without its consequences, serving as the final blow to his engagement before he got dumped. “I was pretty devastated,” Banks said. “I was like, What is wrong with me?”

Lots of other people would be asking the same thing as he began an ill-fated journey that would take him from the courtrooms of Connecticut to a “prison” in Florida to a night sleeping on the floor of a very real jail in New York City.

Banks, 28, a comedian by trade, is recognizable by an unruly mane growing in a 180-degree crown across the back of his head, like Danny DeVito on a bad hair day. He focuses on extended and absurd bits that play out on social media and refuse to wink at the camera. Ongoing projects include his plot to unite the world religions to “eradicate the plague of atheism” and a cultlike movement to convince strangers that he was abducted to the alien planet Car World. Apart from a random encounter with Alec Baldwin in one of his videos, most of this work has yet to gain him an audience much beyond his fellow comedians in Brooklyn.

John Filmanowicz

For his latest project, Banks got some extra firepower from Peter McIndoe, his friend, fellow prankster, and roommate. Over the past eight years, McIndoe had become an expert at getting people to care about inherently stupid ideas, beginning with a movement called Birds Aren’t Real. Founded on a whim in 2017, McIndoe spent years pitching a faux conspiracy that the U.S. government had replaced all the birds with drones to spy on Americans. The meme was a loose commentary on how easily our nation falls prey to QAnon-level inanity. But, like a real conspiracy, Birds Aren’t Real quickly gained hundreds of thousands of followers, became a fixation for young people during the pandemic, and broke containment to the point that their grandparents were hearing about it on 60 Minutes and Fox News. In 2023, McIndoe sat for a prime-time interview with Pete Hegseth, in which he refused to acknowledge that any birds are real and called the current secretary of Defense “Tucker.”

McIndoe wrote a book on the stunt and then faked his own death before moving on to another spoof: buying the patent for Enron for a highly believable satirical reboot. For now, he is remaining off-camera for the stunts; his co-conspirator from his Birds Aren’t Real days is playing the new Enron CEO. “I am definitely in my director era,” McIndoe said. (He also says that last year the Democratic National Committee reached out to him on how to reach younger voters, to which his advice was to “infiltrate the right-wing podcast ecosystem” and “talk upfront about Palestine.” Both ideas were turned down.)

McIndoe, 25, is interested in what he calls “autobiographical reality television.” With the streaming model leading TV and movies to a crisis point, he sees his reality-blending projects as a direct route to get people to pay attention without the nagging influence of a boring suit. “TV and movies are exhausted and overrun by industry and money and bureaucracy,” he said. “It feels banal and it’s been done and I really think there’s an opportunity here to introduce a whole new way to tell stories.”

With Banks going back and forth to court dates, together they saw an opportunity for one of these stories. They would simply start telling everyone that Banks was prison-bound and play with whatever attention came. “We have to find you a real jail,” McIndoe texted to Banks.

McIndoe, Banks, and their two other roommates, Will Duncan and Ryan Smith, wrote out what they called their “roommate passion project.” In their kitchen with Pynchon on the bookshelf and at least two pictures of MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell on display, they got to work writing a story arc for Banks’s fake incarceration on a whiteboard.

In real life, Banks says he agreed to a plan in Connecticut that would result in the charge getting wiped from his record if he agreed to 200 hours of community service and two years of probation as well as taking a psychiatric evaluation and a hate-crime class. But for their show on social media, the gang rented a disused jail outside Miami for a five-hour shoot, hiring a friend from Detroit to play Banks’s cellmate and putting up a casting call for a “jail saga reality show” to fill the remaining roles. Their pawnshop cell phones recorded footage just blurry enough to look real. In total, the shoot was around $6,000, provided by McIndoe.

got a phone pic.twitter.com/pyksUAlfOv

— William Banks (@williambanks_) December 9, 2024

On December 9, 2024, Banks posted his first photo from his fake-prison stint. The stunt was thoroughly believable on X, fitting seamlessly in the trough of “For You” slop and misinformation that feeds the app these days.

Over in the context of a comedy scene that could connect the dots, the reception was not as warm. Banks lost performance opportunities. His improv group, featuring a former SNL member, disintegrated. To keep up the pretense locally, Banks stopped going out as much and began wearing a thinly veiled disguise at times. When we first met at a Bed-Stuy coffee shop called Corto in February of this year, he wore a pair of fake glasses and ordered under the name “Anthony.”

“The key to understanding William is that he has good intentions and really, really commits to a silly idea rather than a harmful or a hateful idea,” said Eric Yates, a comedian and friend who advised Banks on the project. “It was just kind of making fun of how protesters were getting thrown in jail and criticizing this perspective.”

“William freaks people out because I think good art is kind of weird and inappropriate and crosses the line,” said Banks’s roommate Will Duncan. “But I always say, ‘I wouldn’t live like William.’”

The criticism highlighted some incoherence in the project. Was he making light of incarceration? Was he being cruel to Jews supporting Israel? Was he mocking Gaza?

“We’re all chatting about it because there are a lot of people who think that it’s fucked up and stuff, but everyone’s a fucking coward, so whatever,” said comedian Milly Tamarez. (“This is so fucking corny and racist it’s insane,” she had written under Banks’s initial post.) “A lot of their shit in their material relies on an all-white audience and people who have had similar experiences to them,” Tamarez told me. “That’s why it’s funny to him — the idea of Oh my God, what if I went to jail?”

“I just think that using a genocide in any way to gain followers is cowardice,” said another comedian, Marley Gotterer. “People on the streets every day are getting arrested. This whole shtick — it’s not doing what they think it’s doing.”

The prison content kept coming. The narrative showed Banks growing more comfortable in (fake) prison. His (fake) cellmate, a rapper from Detroit who goes by Ant, encourages him to freestyle. (Ant declined to be interviewed about this project unless he was paid $250.) Banks got in a (fake) fight with some atheists in the jail and taught them the healing power of the Abrahamic God. He began calling himself White Moses and, in one dispatch, finally led his fellow fake prisoners to freedom under a chain-link fence.

The roommates were particularly thrilled when an international news account shared a low-def clip of the escape, presenting the video as if it were the real thing.

JUST IN: 🇺🇸🇮🇱 William Banks, a US citizen serving an eight-month jail sentence for stealing five pro-Israel yard signs, escaped custody and posted his breakout on X.

— BRICS News (@BRICSinfo) February 21, 2025

“The funniest part is how many people are interpreting it on the same level that they would as if it was actually happening to a real person, which is the most visceral feeling of entertainment,” said McIndoe. “You go to the movies hoping for a nugget of emotion. I’m hoping something makes me laugh or feel anything at all, even angry.”

Over time, the game of watching Banks online changed. More and more viewers caught on as some of the realism faded. (Where were all the guards in these videos? Why would someone break out of prison with just a few months of a sentence?) But his audience kept growing by the tens of thousands, many of whom couldn’t care less if it were real or fake. “A lot of people are having so much fun with it that they put away their plausible deniability or whatever, and they’re pretending like it’s real,” Banks said. “It’s fun to pretend.” While on the run, Banks found himself a “girlfriend,” a video editor named Madison Van Buren who picked him up off the side of the road following his escape. “People love to see me have a hot girlfriend,” said Banks. “People are like, That’s insane. I can’t believe this guy. A lot of people say I look like Gargamel, the villain in The Smurfs. I don’t like that one.”

John Filmanowicz

This past winter, Banks’s roommate brain trust saw another opportunity. In the second Trump term, people launching and quickly selling their own cryptocurrencies became trendy again thanks to regulators looking the other way. Banks created and promptly cashed in on a meme coin called Moses. He took in at least $50,000, which he then distributed to several charities: $20,000 to the Sameer Project, $10,000 each to the Palestine Red Crescent Society, Translating Falasteen, and Gaza Sunbirds. This part wasn’t fake. Gaza Sunbirds confirmed it received the donation; Hell Gate confirmed the other three donations in a story about Banks published on March 19.

Banks invented a new nickname — Waluigi Mangione — and found what he believed to be a radical moral high ground. “Even though people questioned the ethics of my method, it still raised the most of any of my peers,” he said. “Not to brag about that, but that does feel like definitive evidence that this was a success.” He described the donations as an “iron dome” against critique.

By early March, Banks was putting together the finishing touches on an ending to the jail saga. They planned for the plot to culminate with a wrap party at the Mi Sabor Cafe in Brooklyn, capping his fake run from the law. But the autobiographical reality TV show would have a different finale.

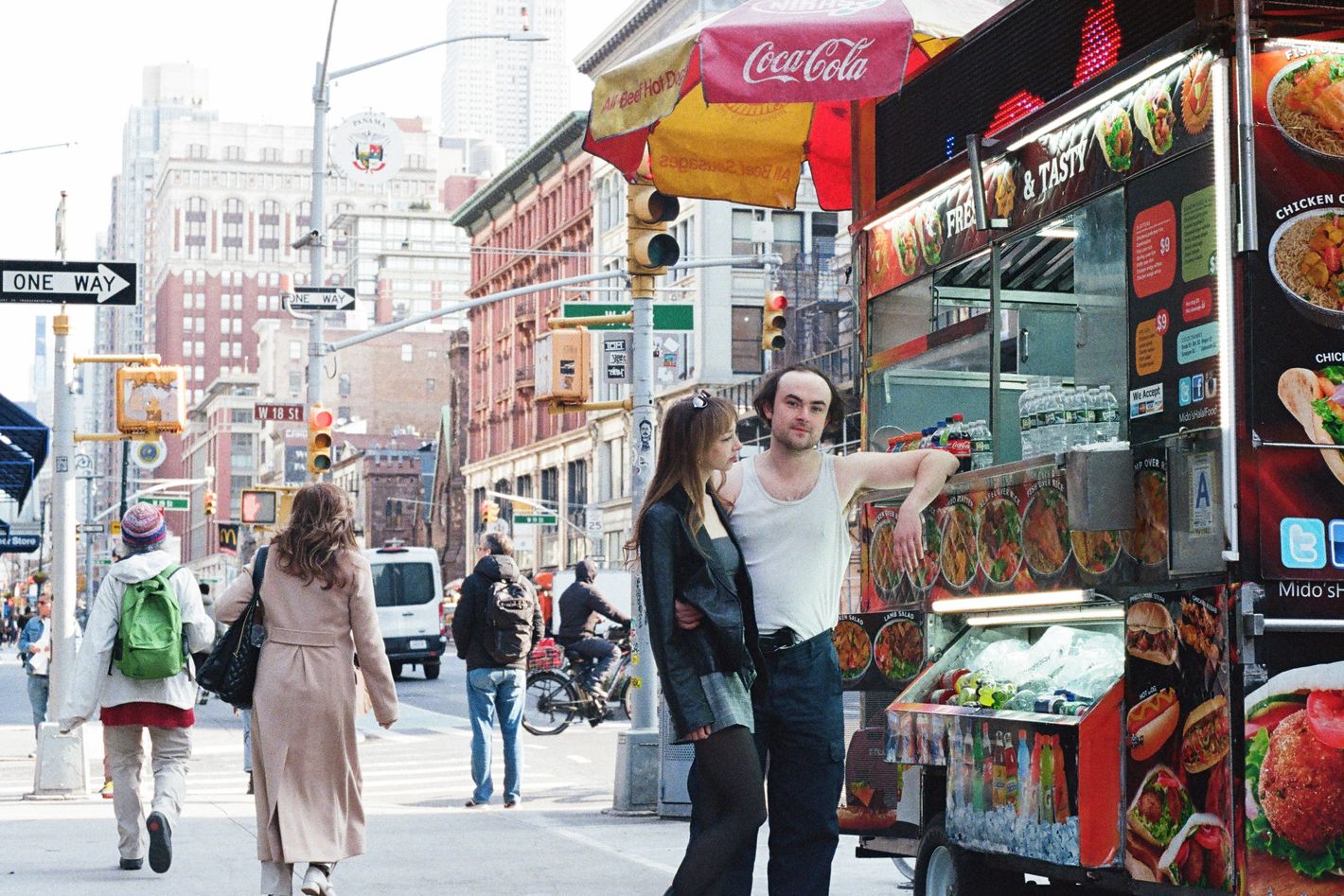

On the morning of March 12, Banks took the train from Crown Heights to Flatiron with his (fake) girlfriend to shoot a few more pictures of himself pretending to be on the run from the law. Minutes after he arrived at a hot-dog cart on West 18th Street, a bystander called 911, reporting that there was a guy in a tank top with crazy hair and a visible gun tucked in his waistband. Like so many things in Banks’s life, the gun was fake — a borrowed BB pistol with the tip painted black. It looked awfully real to the police officers who arrived on the scene and arrested him.

Later that day, I was on the phone with McIndoe when he sent over a picture of Banks being ushered into a squad car. For obvious reasons, it immediately seemed suspect. “I’m being totally honest with you right now,” McIndoe said. “Free William, for real this time.”

The NYPD confirmed the account: Banks had been arrested for possession of an imitation pistol. He was taken to the 13th Precinct, then transferred to Central Booking, where he spent the night. “It’s kind of beautiful in a way,” McIndoe said of his roommate’s unplanned return of the fictional narrative to a hard reality.

John Filmanowicz

Banks did not find as much beauty in his night sleeping on the ground in a cell, using his shoe as a pillow. “Central Booking is way worse than I ever imagined,” he said. But he was satisfied with the new ending to his “film,” as he now refers to his project in conversation. The boys wrote the real arrest into the fake plot: After posting repeatedly that he is “never going back again,” Banks published the photo of the real arrest on March 20, followed by an in-character interview with his “girlfriend,” in which she claimed he was at Rikers.

“It’s become this hybrid reality-fantasy play where it’s both real and not real at the same time,” Banks said. “It’s like quantum storytelling.”

Even as Banks tried to put a bow on whatever all this was, the court dates continued. Released on his own recognizance in New York, he has an appearance in early May for the imitation-pistol charge, which carries a maximum sentence of one year in prison. “I wasn’t planning on getting caught with that gun, but I had kind of got into a bit of hubris,” Banks said. “Now I’m like, I’m not going to hop the subway anymore. I’m going to stop stealing from Whole Foods. I’m going to really be on my good-boy shit.”