Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer/ANDRII BILETSKYI

Jim Acosta, the frequent Donald Trump antagonist who was all but pushed out by CNN earlier this year, may not be the type of person you’d suspect would be a hit on Substack. In fact, when he signed off from his CNN show for the final time at the end of January, he barely knew what it was. “I thought Substack was a place where people posted their articles and opinion pieces,” he said. He could be forgiven for his mistake. When Substack took off in 2020 amid the newsletter boom — which came and went, then came back again, perhaps this time for good — it positioned itself as an email service.

But in the years since, Substack has transformed into something else: a platform for live videos and podcasts, a burgeoning social-media network, and a starter pack for fledgling newsrooms. Every day for the past six weeks, Acosta has been filming himself talking about the horrors of Trump’s second term and posting the video on Substack. To his surprise, there’s an audience for it. Each episode gets between 150,000 and 200,000 views and he has amassed about 280,000 subscribers, more than 10,000 of which are paid.

“The response has blown me away. I did not anticipate this when I left my old job,” Acosta told me recently, speaking from a hiking trail near Sonoma (working for yourself has its perks). “I don’t know where this is going to go,” he added, noting that he was still adjusting to post-CNN life and had just bought his first personal laptop in 20 years. He is, as he says, “living in the moment,” which “may sound too Gwyneth Paltrow for some people.”

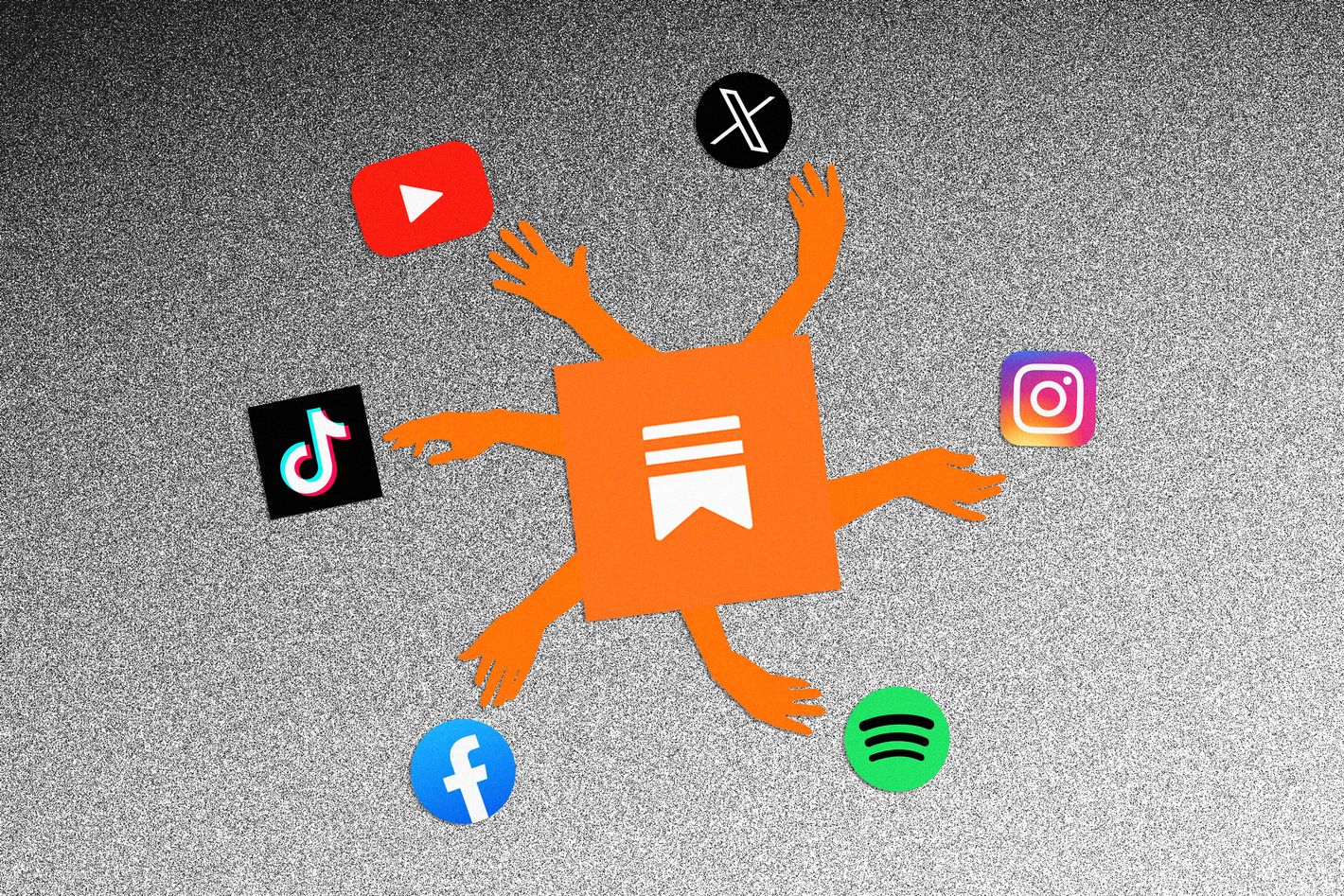

And this is Substack’s moment, it seems. Thanks to a combination of forces — the decimation of Twitter, the collapse of the media industry, the explosion in demand for video and audio content, and the reemergence of Trump — Substack has escaped its humble newsletter beginnings to become a juggernaut collective of independent voices. If you’re looking to start a media operation, it’s now the place to do so: The Free Press, The Bulwark, Zeteo, and The Ankler are among those housed there. If you’re an established journalist or personality looking for your next act — Paul Krugman, Joy Reid, Taylor Lorenz, etc. — do it on Substack. Pete Buttigieg all but announced his future presidential run on there. In a sign of the times, Allure recently announced it is joining Substack to launch a newsletter called The Beauty Chat, even though readers of Allure could presumably get their Allure content from Allure itself.

“When I started my newsletter in 2021, I thought it was an email tool. I was like, Great, it’s a very-easy-to-use MailChimp,” said Rachel Karten, a social-media consultant who used to run social media at Bon Appétit and now writes the Link in Bio newsletter. “And slowly and slowly it’s become a lot more of a social-media tool — there’s now live video and algorithms.”

Substack today has all of the functionalities of a social platform, allowing proprietors to engage with both subscribers (via the Chat feature) or the broader Substack universe in the Twitter-esque Notes feed. Writers I spoke to mentioned that for all of their reluctance to engage with the Notes feature, they see growth when they do. More than 50 percent of all subscriptions and 30 percent of paid subscriptions on the platform come directly from the Substack network. There’s been a broader shift toward multimedia content: Over half of the 250 highest-revenue creators were using audio and video in April 2024, a number that had surged to 82 percent by February 2025.

Substack initially rolled out livestreaming in September as a feature available only to publishers with a lot of subscribers; in January, it made live video available to everyone. There’s a collaboration feature that allows you to co-host streams with up to three people, “essentially what is one step up from a public FaceTime call,” says Substack co-founder Hamish McKenzie. “It lowers the barrier to entry to saying something important in public; it’s also kind of fun.” Acosta has kept his videos free for now, but others are offering the feature only to paid subscribers, as Tina Brown has for recent conversations with Maureen Dowd and Janice Min.

“Email is something that we will absolutely never abandon,” said McKenzie, noting it’s “important as a guarantor of that direct owned relationship that the writers and creators can have with their audience.” But by limiting yourself to just email, “you’re tying one of your hands behind your back.” When someone like Acosta goes live on Substack, they announce that they’re doing so to their entire email list, who can then jump on and watch. At the end of the stream, they are presented with the full video, which they can then blast out to their Substack followers as well as post on other social platforms.

But even those who’ve resisted new features and kept their newsletters largely text based continue to see an uptick, like journalist Max Read, who writes the twice-weekly Read Max newsletter. “To the extent there’s been a Trump bump in the media, it’s all going to Substackers. I cover tech, not really politics. But I saw incredibly fast growth — it seems to finally be plateauing — between late October/the election last year and two or three weeks ago,” he said. “I was growing twice as fast as I’d been in the months before that.”

Sports journalism has basically migrated to the platform, and food media seems not far behind — if not already there. In the past few months, renowned cookbook author and restaurateur Yotam Ottolenghi joined Substack, as did Ballerina Farm influencer Hannah Neeleman. “That’s just such a clear indicator to me of how much money there is to be made,” said chef and writer Clare de Boer. “There’s no one that is too big for Substack.” Live video seems particularly suited for the food category. Substack last week hosted a live three-day food festival called Grubstack featuring top food writers and chefs like de Boer, José Andrés, Ottolenghi, Caroline Chambers, and David Lebovitz participating in live conversations, cook-alongs, and virtual tastings.

Substack as a whole this month celebrated 5 million paid subscriptions — including 2 million to outlets that publish video — less than four months after it crossed the 4-million milestone. And it is intent on cracking new territories. “Substack’s bread and butter has been journalists and analysts and academics and bloggers, which is a really elite class and very influential, but it’s small in its total size compared to where most of culture is happening right now, which is on Instagram and TikTok and YouTube,” said McKenzie. Substack saw opportunity amid the looming TikTok ban, offering a $25,000 prize to the creator who produced the most convincing video inviting their TikTok audience to Substack. “We’re going to rescue the smart people from TikTok!” Substacker co-founder Chris Best wrote.

The winner of that competition was Aaron Parnas, a 25-year-old D.C.-based creator who used to practice law but now practices Substack. “More or less my audience has followed,” said Parnas, noting the “biggest thing has really been just introducing this new platform to them,” because “a lot of folks don’t really know what Substack even is.” He posts two to three videos a day in which he basically talks through the day’s big headlines. Around 370,000 people subscribe — “98, 99 percent of those subscribers are in the past two months,” he says — and more than a thousand are paid. He typically reserves livestreams as a perk for paid subscribers.

The initial dream that Substack sold of individual journalists making a living through subscriptions has been eclipsed by a new hybrid model. More and more, people aren’t on there to make money at all but to promote their stories and books and engage with fellow media types without being trolled by Elon-worshipping Nazi bot accounts (though Substack has its own Nazi problems). Meanwhile, money can feasibly be made from sources other than subscriptions. “I felt like Substack was against brands and advertising early on. Now that more brands are joining, it does seem like it is welcoming them,” said Karten, pointing out that Substack had hosted a joint event with luxury resale platform The RealReal at the Manhattan restaurant King on Tuesday evening. “As a user, it makes me wonder if we might start to see ads in Notes. As a marketer, I see the opportunity — but it can be a slippery slope.”

The cynical take is that Substack — which takes a 10 percent cut of the paid subscription revenue — has shifted to trying to make money off only high-profile people. But the reality is there aren’t many other places offering the kind of new venture that Substack has made possible for so many big names.

“Writers were not the obvious sexy customers to be building the tech company around,” said McKenzie. But early on, he remembers talking with Best about how different it’d look if “social networks had been built on subscription models rather than advertising,” and how one day Substack could organically develop into its own ecosystem — which it now seems like it has. “As we matured and got more people using Substack over time,” McKenzie said, “these wild imaginings became much more like plans.”