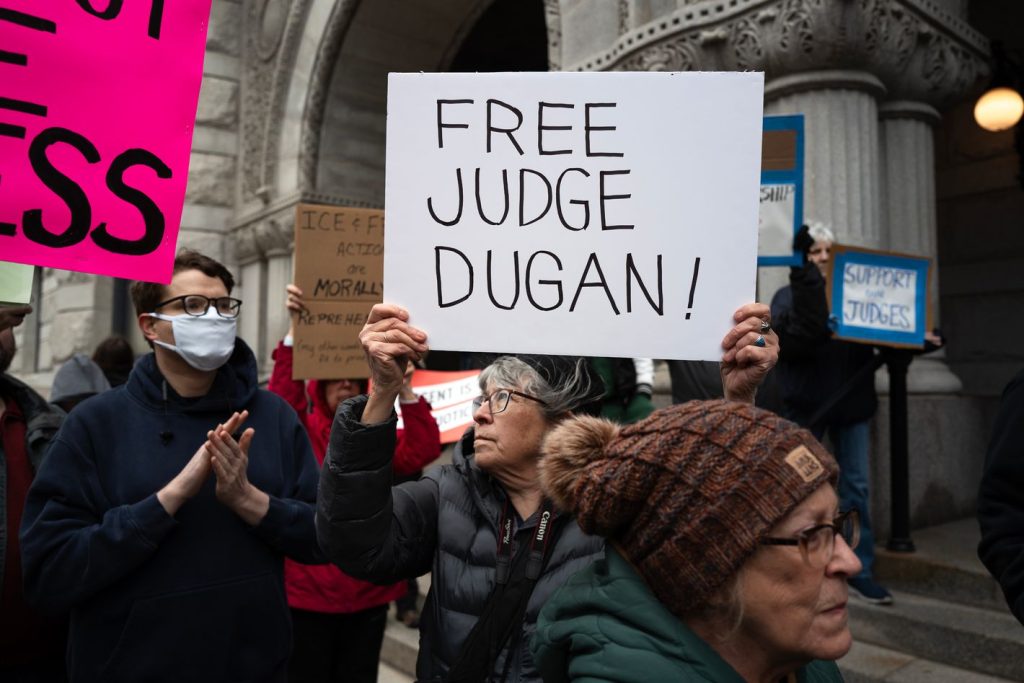

Photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images

There’s plenty of cause for alarm over the Trump administration’s enforcement of its immigration agenda during its first three-plus months back in power. But the recent arrests of two state-court judges — Hannah Dugan in Wisconsin and Jose Luis Cano in New Mexico — are not part of the problem.

Don’t conflate these well-founded criminal charges with the many valid and pressing criticisms of the Trump administration on immigration. Both of these judges crossed a line, and both criminal charges are justified (even if Judge Dugan is exceedingly unlikely to be convicted, as we’ll discuss in a moment).

Before we dig into these cases, a baseline proposition: It’s not a crime to do nothing. No state governor or police department or judge — or even civilian — has any affirmative obligation to help ICE agents or other federal agencies do their work. This is why I’ve publicly criticized Trump’s Justice Department for threatening to prosecute state and local officials who merely decline to cooperate with the Feds on immigration enforcement. There’s nothing there.

But the criminal cases against Judges Dugan and Cano are different. They’re not about mere declinations to comply — they’re about intentional acts of obstruction. Both judges crossed that crucial boundary between doing nothing to help and getting in the way. Both judges knew better.

Cano’s case is the easier one. The former New Mexico state judge allegedly housed three Venezuelan citizens who were in the U.S. illegally; one was a suspected member of the Tren de Aragua gang. According to a federal criminal complaint, Cano admitted to law-enforcement agents that he had used a hammer to smash the suspected gang member’s phone because it may have contained incriminating photographs of that person holding guns. We need not linger on this one; destroying a cell phone with a hammer to prevent the Feds from getting evidence is textbook obstruction.

The Dugan case is more complicated and her conduct less flagrant (though still over the line). On April 18, a team of federal agents went to the state courthouse in Milwaukee to arrest Eduardo Flores-Ruiz, a Mexican national. Flores-Ruiz came to the U.S. illegally, was deported in 2013, then returned (again) illegally. He was scheduled to appear in Judge Dugan’s courtroom on April 18 because he had been charged with domestic abuse, battery, and infliction of physical pain or injury.

Federal immigration agents learned of Flores-Ruiz’s impending court appearance and planned to arrest him inside the courthouse pursuant to an administrative immigration warrant. There is nothing unusual or improper about a courthouse arrest. Law-enforcement agents know the suspect will be in a certain place at a certain time, unarmed (because he must pass through magnetometers at the entrance). It’s safer to make an arrest at a courthouse than during a traffic stop or on a street corner or during the execution of a search warrant at a private home.

The criminal complaint against Judge Dugan — which was reviewed, approved, and signed by a federal magistrate judge — details the events inside the courthouse on April 18. Judge Dugan confronted the federal agents; claimed (wrongly) they could make an arrest only with a judicial warrant but not an administrative warrant; told them (again, wrongly) they would need to leave the public courthouse; and instructed them to go speak with the chief judge. The agents complied, and the chief judge told them to make their arrest in a public area of the courthouse.

Meanwhile, Judge Dugan returned to her courtroom, where Flores-Ruiz and his attorney were waiting, among other litigants. According to the judge’s own deputy, the judge was trying to push Flores-Ruiz’s case through quickly. Indeed, the judge adjourned (postponed) the Flores-Ruiz case without notifying in advance or consulting with the prosecutor who was in the courtroom on that case — or Flores-Ruiz’s victims, who also were present and entitled by Wisconsin law to be treated with “fairness, dignity, and respect.”

After the judge’s secretive, expedited adjournment, Flores-Ruiz and his lawyer walked toward the public courtroom exit; federal agents waited outside that door to make the arrest. But, according to her courtroom deputy, Judge Dugan “said something like, ‘Wait, come with me,’” and then “escorted” Flores-Ruiz and his lawyer through a “jury door,” which leads to a nonpublic part of the courthouse. According to the deputy, a non-incarcerated defendant like Flores-Ruiz would never be permitted to use that jury door in the ordinary course. After leaving through the jury door, Flores-Ruiz eventually got out of the courthouse and ran. Federal agents caught and arrested him on the street.

Judge Dugan hardly committed the most egregious act of obstruction. I’ve worked on cases where witnesses have been murdered, evidence has been burned or flushed, jurors have been threatened, files have been deleted. The crux of Judge Dugan’s conduct was to direct and usher Flores-Ruiz out the back jury door. But her intent, as laid out in the complaint, was plain: She wanted to help him evade the federal agents who had come to arrest him — and succeeded, briefly. (Imagine how the victims of Flores-Ruiz’s attack felt, sitting in that courtroom and watching the judge cancel the scheduled proceedings and hustle him out the back door, away from arresting officers.)

While the complaint against Judge Dugan makes out a valid criminal charge, the odds of an ultimate conviction are minuscule. It will come as little surprise if a federal district-court judge dismisses the case, or even if a grand jury declines to indict; the politics around this case run hot, and it feels precipitous to prosecute a judge for her conduct inside her own courtroom. Attorney General Pam Bondi made matters worse when she amateurishly gloated on Fox News about prosecuting “deranged” judges; that improper public commentary also could provide a hook for dismissal if a federal judge is determined to find some off-ramp.

If the case makes it to trial, it’ll be exceedingly difficult to convince a jury of 12 Wisconsin residents to convict Judge Dugan given the politics around the case. Wisconsin is split roughly in half; Trump won the state in 2024 by less than one percentage point. Jurors who oppose Trump or his anti-immigration policies will have a hard time putting aside their political views, no matter the actual evidence. Consider, for example, a poll posted by my CNN colleague and SiriusXM host Michael Smerconish (who has a diverse but generally moderate, centrist following). Of more than 35,000 respondents, over 51 percent said that even if a judge helps a migrant evade arrest by ICE, that judge should not be arrested and charged with obstruction. That’s an ominous indicator for prosecutors.

Trump has already given us plenty of real problems on the immigration front: The erroneous, process-free deportation of Kilmar Abrego Garcia and the administration’s ensuing defiance of the spirit (if not quite the letter) of court orders to “facilitate” his return; the invocation of the ancient, wartime Alien Enemies Act to deport planeloads of detainees, accompanied by a mad scramble to avoid judicial scrutiny and (again) near defiance of a valid court order; the deportation of children who are U.S. citizens without meaningful process; outrageous public verbal attacks on judges who have ruled against the Trump administration; and unthinkable threats by the president to deport U.S. citizens to foreign prisons.

But both Judge Dugan and Judge Cano did wrong. They’re not martyrs or heroes. And their deification only distracts, and detracts, from the real case to be made against Trump’s destructive immigration enforcement tactics.