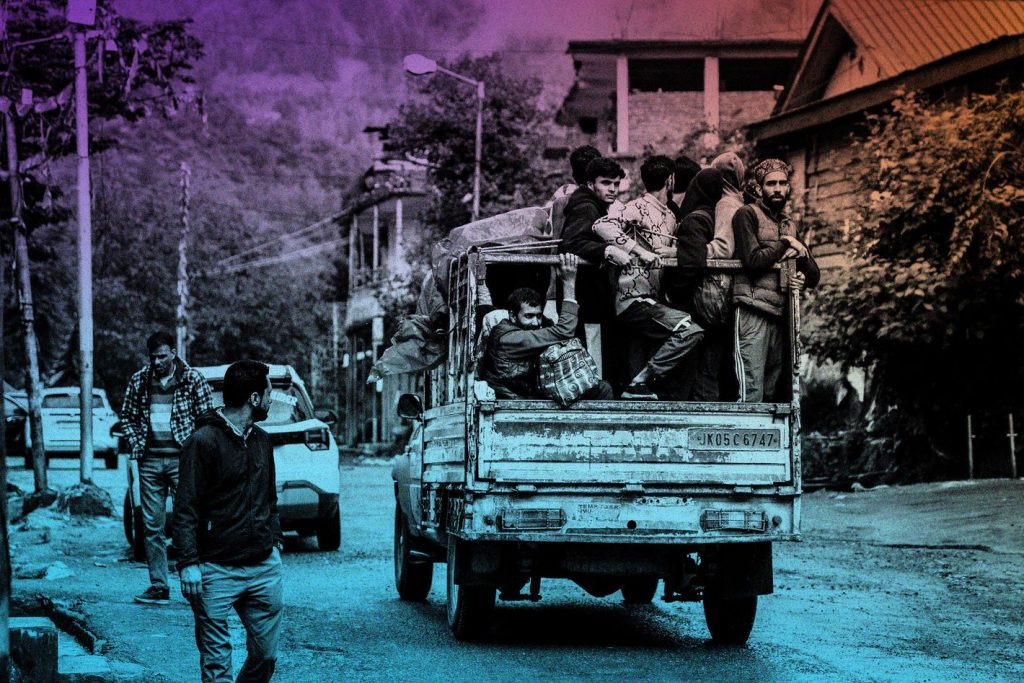

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Photo: Getty Images

After four days of deadly fighting between India and Pakistan that seemed near the edge of catastrophe, the two sides abruptly agreed to a U.S.-brokered ceasefire on Saturday. The conflict began with an April terrorist attack by Pakistani militants in the long-disputed region of Kashmir, during which gunmen shot and killed 26 people at a popular vacation spot in the Indian-administered part of the region. India accused Pakistan’s government of being behind the attack, a charge Pakistan denied.

Last week, India hit Pakistan with airstrikes deep into the country, killing dozens, but Pakistan shot down multiple Indian planes. India accused Pakistan of a drone attack near the Kashmiri line of control, which Pakistan denied; India responded by targeting Pakistan’s air-defense systems. It was the latest chapter of hostilities between the nuclear-armed countries, which have simmered since Partition in 1947 and flared up many times since, including a devastating 1971 war (which led to the creation of Bangladesh) and several skirmishes, most recently in 2019. For some insight on how India and Pakistan got to this point, the fragility of the current ceasefire, and the American role in all of it, I spoke with Manjari Chatterjee Miller, who is a senior fellow for India, Pakistan and South Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations and a Professor of International Relations at the University of Toronto.

India and Pakistan could both spin the results of this conflict quite positively. India hit the supposed terrorist sites in Pakistan and some of the country’s defense systems, and Pakistan shot down at least two planes and infiltrated Indian airspace with drones. Do you think both sides came out with enough to claim some kind of victory and mollify things for a while?

I would not call the last four days an unmitigated win for India. On the one hand, we have now seen the extent to which India is determined to act in its self-defense; clearly, India is no longer hesitant about escalation. In the past, we had talked about how the threat of nuclear escalation, particularly low-yield weapons, was a reason to hold back. We see that India is very willing to engage in conventional warfare to defend its interests and to protect its territory. But in terms of the actual success of the strike — sure, they hit sites in Pakistan, but India also lost fighters. They can’t say “We obliterated Pakistan’s air defenses and took out their fighter jets and hit all of the terrorist sites and we did it without taking too much damage or casualties on our side.”

But the part that I think is really not a win for India, and really also not a win for India-United States relations, is the U.S. mediation. Kashmir is India’s sovereign issue, and it has never accepted third-party intervention or interference in Kashmir. And then you have President Trump saying he’s happy to find a “solution” to Kashmir.

And if you think about where India is geopolitically, it needs a win. It needs to show that it’s been successful in deterrence. For the last 10, 15 years, India has been growing beyond the region. Two or three decades ago, when the U.S. relationship with India was not so good, one of the reasons is that we kept talking about India-Pakistan, India-Pakistan. That hyphenation was something the Indian government absolutely hated. In the last 10 to 15 years, the India-United States strategic partnership has completely transformed the relationship. Part of it is because we’ve de-hyphenated India and Pakistan, so when you think about India, you no longer think, “Oh, that pesky conflict with Pakistan. These regional powers are just squabbling.” That kind of narrative shifted for India.

It became all India, almost no Pakistan, right?

Exactly. So it’s India as the rising power, India as the leader of the president of the G20. Here is India inviting the African Union into the G20. Here is Modi visiting President Trump right away after he’s inaugurated, and there’s JD Vance in Delhi just a couple of days before the attack. The narrative around India has changed so much. And what this does is it pulls India back into the narrative of “Well, it can’t even control its border, can’t really get beyond the region, and there’s this constant instability.”

India is actually denying that the U.S. mediated this ceasefire.

Yeah, whereas Pakistan has gone out on a limb and thanked the United States. And here’s what’s interesting: It also thanked Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar, in addition to China and Turkey. With China and Turkey, you can say, “Okay, they supplied drones and supplied fighter jets, air defense systems.” So you can understand that. But why the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia? I wonder to what extent those countries rushed to the U.S. as well and pressured the Trump administration to do something.

That speaks to what a global conflict this was, even though it was nominally between two countries.

I do think it was interesting in terms of the test of Chinese weapons. The Chinese gave Pakistan military equipment and logistical support, and some of it performed. You had Chinese-made fighters that shot down Rafales, French-made aircrafts. That’s the first time we’ve seen those fighters in action. And then you have the French SCALP missiles that India used, which went pretty deep into Pakistani territory and performed well against Chinese-made air defenses, because they penetrated without detection. And then Pakistan supposedly used Turkish drones, and India supposedly used Israeli drones.

We talk about this as a conflict of global implications today, but this conflict had global implications since the Soviet War in Afghanistan. These terrorist groups are an outgrowth of that war. They’re born from that mujahideen war, and so it’s always had global implications from the 1980s onwards in terms of these groups.

Well, this conflict has been internationally important since Partition in 1947, right?

Yeah, but in different ways. We always talk about the Kashmir conflict, and we never acknowledge that the conflict in 1947 is not the one of 1965; it’s not the one of 1971; it’s not the one of the 1980s, and it’s definitely not one of the 1990s.There’s certainly a root thread that runs through it of national identity and symbolism, but the actors and agents and the ways and means have changed so much that in some ways the conflict today is an entirely different one from 1947.

Can you expand on that?

In 1947, you had a war between India and Pakistan, just as they became independent. And the reason for this was — Pakistan was the first country in the world that was founded on the basis of religious nationalism. And the idea behind Pakistan was that, essentially, the Indian subcontinent is home to two different communities, two nations — Hindu and Muslim. Jinnah, known as the founder of modern Pakistan, was the head of the Muslim League Party, whose idea was that the Indian National Congress party could represent the interests of the Muslims on the subcontinent. The Congress party disputed this. Its nationalist claim was about secularism, and it was a very different kind of secularism than in the West, where it was about the state representing the interests of every religion rather than saying the state is out of the business of religion.

By the time you get to 1947, Pakistan has been carved out of two provinces, Punjab and Bengal, which have Muslim majorities. And when I say Muslim majorities, we’re talking about the difference of a few million. The majority of Muslims in the subcontinent itself are left behind in India.

So you have two different parts of the Indian subcontinent that are unconnected — what the Muslim League called a moth-eaten Pakistan. Just imagine if you had the East Coast and the West Coast being one country, but the Midwest being a completely different country in between. It’s ludicrous, right?

How does Kashmir fit into all this?

There’s one more question, which is what the heck to do with all of these states inside the Indian subcontinent that are called the princely states, which have Maharajas — Muslim rulers. Because they did not have direct British rule. They had indirect British rule, and were nominally autonomous. So they give them a choice: join one or the other. And then you get to the state of Kashmir, which is a Muslim majority state, but it has a Hindu dynasty, a Hindu ruler who’s not popular among his subjects — not because he’s Hindu, but because he’s a pretty bad ruler.

And it becomes crucial to both states’ identities. For Pakistan, a Muslim majority state on its border has to be part of Pakistan. It doesn’t make sense for it not to be if you’re claiming to represent the interests of Muslims. But for the Congress Party, it’s crucial because how do you show that you’re the secular party representing everybody’s interests if you can’t govern a Muslim majority state? And Nehru himself is Kashmiri, a Kashmiri Hindu.

So in 1947, for various reasons, they went to war in Kashmir. It started off as a proxy war where you had these tribesmen — we still don’t know who they were or who sent them, but we know there were Pashtun tribesmen who invaded Kashmir. At this point, the Maharaja asked India for help, and India said sorry, we don’t intervene in the sovereign affairs of other states, but if you join us, we’d be happy to help. He legally sent the instrument of accession. India sent troops in, Pakistan aided the tribesmen, and you had the first war and a stalemate, and the line of control drawn.

This is the other piece of the pattern. A few weeks before the attacks, Pakistan’s army chief, General Munir, gives an address, and talks about the two-nation theory and Kashmir being the jugular vein of Pakistan. That’s pretty potent stuff, and it’s inflammatory to the Indian government because you’re basically saying that you still subscribe to this idea that Muslims have separate interests from Hindus, and you still subscribe to the idea that without Kashmir, Pakistan’s existence is meaningless.

India has accused Pakistani authorities of being involved in the terrorist attack that set all this off. Is there any notion of whether that is true, there’s any truth to that, or is it just like a total morass of, as you said, fuzzy information and nobody really has any idea?

There is no smoking gun, and the Indian government — I think this was a sign of their confidence — didn’t bother to actually show evidence. There was no attempt to try to convince the international community. What I will say is that there has been a pattern of terrorist attacks on Indian soil by terrorist groups that we know are based in Pakistan. That’s not a secret. We know that the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed are headquartered in Pakistan. We know that they actually have charitable operations, even in Kashmir. We know that the leaders are living in Pakistan. We know that they’re not in jail, that they’re nominally under house arrest, but actually have the freedom of movement.

We also know there’s a pattern of attacks that happen at interesting moments. India, I think, is the only country where you’ve both had a head of state visit and a very senior official visit the U.S. within Trump’s first hundred hundred days. And then you have the attacks like a day after that — when, you might say, it’s a good moment to remind the world that Kashmir is not resolved.

What about Modi’s political position? He’s been weakened somewhat, after his party didn’t do as well as expected in last year’s elections. Do you think this strengthened his hand in going forward domestically?

Well, certainly the domestic media is spinning everything as a win, a hundred percent success in every way. So we’ll see. The misinformation that’s swirling around has been insane. India, for example, claimed it’s taken out Turkish-made drones that Pakistan sent in. It’s been all in the Indian news. I haven’t seen any third-party news reports that have confirmed that. And there have been so many blackouts, so many Twitter accounts taken down on both sides, that it’s very, very hard to know exactly what happened, where, when, and why and how many

But I would say that the region is more dangerous today than it was four days ago. Because what you’re seeing is that with each terrorist attack, India’s gone further into Pakistani territory. And the Pakistan military is either unwilling to or unable to control these militants.

So where does this leave things? Does India want another chance to get that unmitigated win? Modi said India has only “paused” its military activity.

What you’re asking is whether there’s a chance of the crisis breaking out again?

More like — could the next, slightest provocation, lead to something really bad?

Yes. One Hundred percent.

This interview has been edited from two conversations for length and clarity.