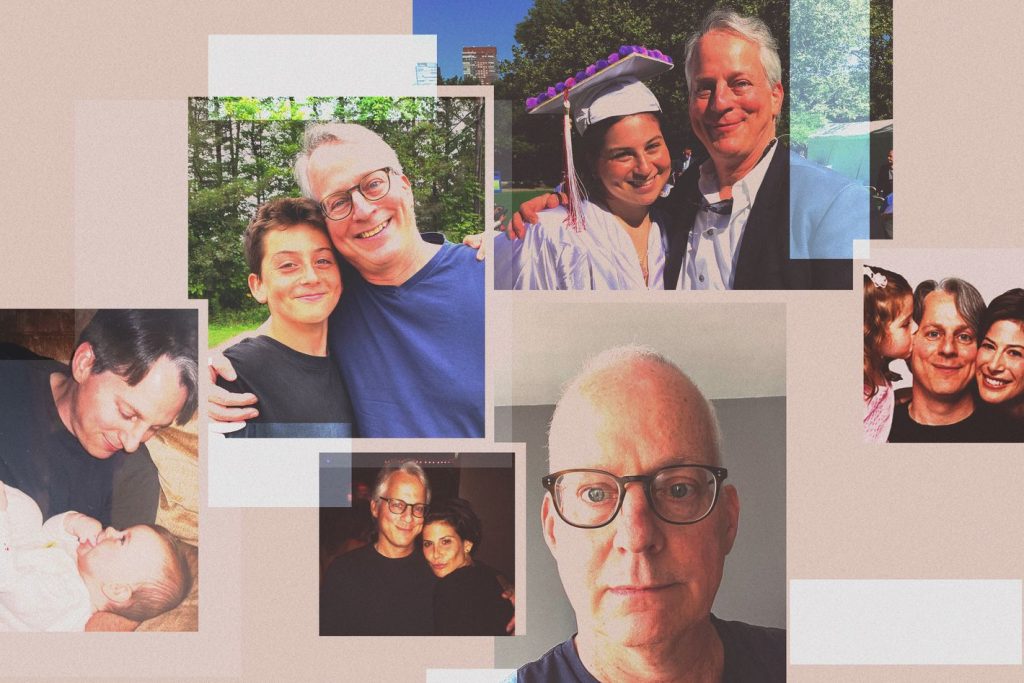

Photo-Illustration: New York Magazine; Photos: Jon Gluck

Cancer stories, as we’ve long told them, tend to follow one of two arcs: diagnosis, then a brave fight against the disease resulting either in survival or death. But journalist Jonathan Gluck’s story has been different. When he was 38, with a wife and 7-month-old at home, Gluck learned he had multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells that causes damage to bones, kidneys, and the immune system. It’s an uncommon form of cancer with an estimated seven people out of 100,000 diagnosed each year. Those who are diagnosed tend to be older; less than one percent of new cases occur in people younger than 65. Multiple Myeloma is incurable, and initially, Gluck was told he would likely live another 18 months to three years. But that was more than 20 years ago.

In his forthcoming memoir, An Exercise in Uncertainty, out on June 10 from Harmony Books, Gluck details the reality of life as a medical marvel, including the remarkable nature of his survival thus far and the subsequent impact his disease has had on his family and career. The book covers his experience undergoing breakthrough treatments for his disease, as well as charming passages on his chosen coping mechanisms (a regular poker game with friends and a rabid passion for fly-fishing).

Living long term with cancer is an experience most of us don’t hear much about, even though it is increasingly common. The American Cancer Society reports that the overall cancer mortality rate fell by a third between 1991 and 2019. In multiple myeloma patients specifically, the five-year survival rate was about 35 percent in the early 2000s, up from about 29 percent in the early 1990s. Today, according to the most recent statistics from the National Cancer Institute, that rate has climbed to 62 percent. “That means more people are surviving the disease and going on to live their lives, many of them for prolonged periods,” writes Gluck, who for a decade was deputy editor of New York.

These stats can sometimes obscure the reality of living with cancer as a chronic illness. “Most people think, If there’s a treatment, you take it,” he told me. “And if it works, you get better. And that’s that.” It is so much more complicated than that, he said. For Gluck, living with multiple myeloma has meant countless hours lost to administrative work, like scheduling appointments or battling with his insurance. (Once, early on in his treatment, his doctor’s office lost all his medical records in a flood.) It has also meant suffering long-lasting side effects of treatment and going to work, anyway, in part because not working is not an option. And all of that is underpinned by a persistent sense of dread: Each time he enters remission — and he is currently in remission after undergoing a type of immunotherapy called CAR T-cell therapy in 2023 — he knows it’s not a matter of if but when the cancer will return. His book is an attempt to answer the question so many have asked him over the years: How do you live with that level of uncertainty?

For years, his answer essentially was: You don’t. As long as he could, Gluck kept his cancer life tightly cordoned off from his non-cancer life. Two summers ago, in a cab on the way to a treatment session, he was idly reading a news story about the growing number of patients who were living with cancer as a chronic, treatable disease. “I was like, Gosh, how interesting,” he said when we spoke in April. And then it clicked — he was someone like that — and he let out a gasp so loud the cab driver turned around to ask what was wrong.

Before writing the book, he didn’t talk about cancer much. “And for the most part, believe it or not, I didn’t think about it that much,” he told me, “because I just wanted to lock it away in a box as best I could.”

When his children were very young, he and his wife kept his illness secret from them. (In a brief, lovely scene, Gluck finally shares his diagnosis with his then-11-year-old daughter in the back of a cab, on their way to Bloomingdale’s to buy an elementary-school graduation dress; shortly thereafter, he told his son, who was 6 at the time.) “There was cancer, and there was me,” he writes about this intentional bifurcation of his illness life and his non-illness life. “If the first of those entities wasn’t integrated into the second, perhaps I could ward it off more easily.” It worked until it didn’t.

If Gluck’s cancer story has a definitive starting line, he and I are standing on it. On a recent Saturday afternoon, we met outside the office building on Broadway where, in November 2002, he slipped on a patch of ice and twisted his left hip. The pain persisted for a year, which prompted an MRI, which prompted more tests, which eventually led to his cancer diagnosis. “Sometimes myeloma simmers for a lot longer, and by the time you’re symptomatic, you can be in bad shape,” he said. “So in a weird way, and I use the term advisedly, I was lucky.” (In a 2007 piece for New York, Gluck wrote about his illness for the first time, and the story starts with that slip; his book begins the same way.)

He doesn’t look sick, I think but don’t say out loud as we walk to Washington Square Park. Later, as we sit and chat on a bench, Gluck brings it up himself; he gets that a lot. It’s not always the compliment people think it is. “If you don’t have overt signs of your illness, people sort of forget you’re sick,” he said. “I’m going to go a step further and say they almost don’t believe it when you tell them.” (He and I briefly crossed paths in 2019 when we both worked at Medium, and at the time, I had no idea he was ill.)

The only giveaway right now is the mask hanging from the crook of his elbow. In 2023, Gluck started CAR T-cell therapy, which was approved for use in some multiple myeloma patients a little more than one year before Gluck needed it. Again and again, Gluck has managed to stay just ahead of new treatments for his disease. In 2006, three years after he first learned he was sick, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a combination chemotherapy regimen known as RVD for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. “Glück is German for luck,” he writes, somewhat wryly.

CAR-T therapy, as it’s sometimes called for short, is an immunotherapy, meaning it uses the patient’s own immune system to fight their cancer. (On Tuesday, the Journal of Clinical Oncology published a study showing that a third of the patients with Multiple Myeloma who received the treatment as part of a clinical trial still have not seen their disease return, even five years later.) Before beginning the treatment, Gluck was optimistic (“action is better than inaction,” he writes) but wary; the process would require a months long preparation period as well as hospitalization, and he’d be risking potentially debilitating or even fatal side effects.

The treatment put him into remission, but it also left him immunocompromised. (The therapy wipes out some patients’ immune systems to the point that they need to get certain childhood immunizations again, Gluck writes.) Since undergoing CAR-T therapy, Gluck has been practicing strict COVID-like protocols, though he’s lately relaxed that a bit; recent testing of his T cells and other markers has shown his immune system is on the mend. He now commutes to his job at Fast Company, where he started a new role this year, and works in an office around people, although he wears a mask in large meetings and tight spaces. Before we met, he intimated that, all things being equal, he’d prefer to meet outdoors.

During one of the preparatory treatments for the CAR-T therapy, he lost his hair, finally experiencing what might be the most famous cancer side effect. At the end of the therapy, when he learned he was in remission, he felt — and he was — altered on a “cellular level,” unable to continue compartmentalizing his illness. “After my CAR-T therapy, that changed,” he writes. “The scope and seriousness of the treatment rendered the illusion no longer believable.”

For nearly as long as he’s had cancer, Gluck has been haunted by a recurring dream.

He was diagnosed with the disease in 2003, when the medical advice people liked to give each other was to trust your doctors and stay off the internet. But Gluck couldn’t resist. (“Not knowing things makes me anxious,” he writes.) The night after learning he could have multiple myeloma, he stayed up late learning everything he could about the disease, eventually stumbling across a series of X-rays of a myeloma patient.

“Their bones were literally just full of holes — they looked like Swiss cheese,” he told me. Myeloma cells disrupt the normal bone remodeling process by overstimulating osteoclasts, the cells that break down old bone tissue. This causes osteoclasts to become much more active than normal, leading to aggressive bone destruction that outpaces the body’s ability to rebuild bone. “And that image — and just that idea, that this disease can eat through your bones like that — has been hard to shake,” Gluck said. “I still have nightmares about it.”

At one point in the book, he speaks fondly of the usefulness of denial. “I used to think of denial as a pop-psychology cliché. Not anymore. Denial is a vital human coping mechanism. It helps cushion life’s inevitable blows.” (Most of Gluck’s sentences are like this, controlled and brief and matter-of-fact, like he’s trying to get down on paper what he does know for certain.) When he recognized himself in that article on long-term cancer survivors, it was one of the first times he admitted to himself that he couldn’t keep his sick and well lives separate forever. The CAR-T therapy was another. In a way, writing the book is a public admission that the disease isn’t just part of his life. “For those of us destined to live with cancer as a permanent condition,” he writes, “it is our life.”

When we met in early May, he’d recently had one of those nightmares. The dreams always go the same way. He’s doing something mundane, like cooking dinner, and not thinking about his illness. And then he opens a drawer and — jump scare — that image of Swiss-cheese bones appears. It doesn’t take a psychoanalyst to do some dream analysis here: As much as he’s tried to keep his illness safely tucked away, it’s still there.

Related