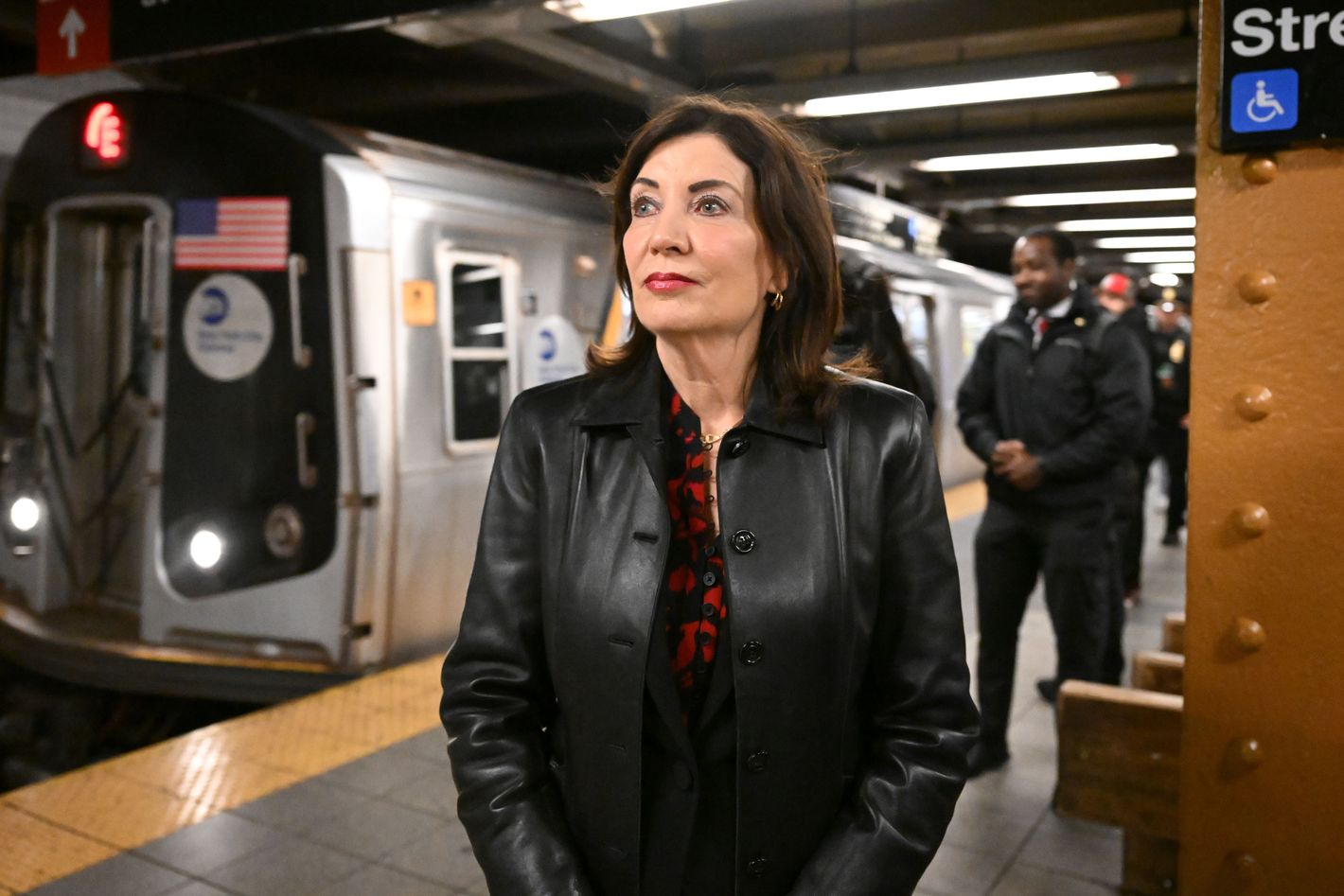

Photo: NDZ/Star Max/GC Images

Governor Kathy Hochul sometimes reminds me of my first teachers, the mostly Irish nuns from the Dominican Sisters order who ran the Annunciation School on West 131st Street in Harlem in the 1960s. I remember the nuns as happy and kind as they rushed around in their plain black-and-white habits, with an underlying no-nonsense energy rooted in the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience the women had taken. (Kids who misbehaved could, in those days, be sent to the principal for a paddling.)

Hochul, who attended law school at Catholic University, recently told me, with that friendly but unyielding nun vibe, that she has no qualms about delaying passage of the already overdue state budget in order to reform New York’s criminal-justice laws to provide greater protection to victims of domestic violence.

“My mother was in a home where there was domestic violence, and she grew up to be a champion, an advocate. When I was in high school, I watched my mom fight for them. We opened a home for victims of domestic violence,” Hochul told me. “When my mom used to take women into court and sit with them and have a case come up when they weren’t able to keep the defendant held and get an order of protection, the woman had to go home and know that person is out there still stalking her and her children. This is what I’m fighting for.”

The governor, backed by groups like Sanctuary for Families, an organization dedicated to helping victims of domestic violence, says an alarming 94 percent of domestic-violence cases are being dismissed due to overly restrictive laws governing the gathering and exchange of evidence between prosecutors and people accused of crimes, a process called “discovery.” For decades, New York had a terrible practice of allowing prosecutors to delay giving critical exculpatory evidence to defendants, who often pleaded guilty when they might have had a chance at acquittal, which in some nightmarish cases led to innocent people spending years behind bars.

Many New Yorkers know about the travesty of justice in the case of Kalief Browder, a Bronx teenager arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack full of valuables who languished on Rikers Island for more than two years, refusing to plead guilty. It eventually turned out that prosecutors had no witnesses or other evidence, but Browder’s long, violent stretch in custody contributed to his suicide after leaving Rikers.

In 2019, the legislature fixed the long-standing injustice by passing a bill (Kalief’s Law) that requires prosecutors to round up a designated list of 21 evidentiary items, such as the footage of body-worn cameras, the notes and disciplinary records of arresting officers, the interviews of all witnesses to a crime, and so forth, with a mandate to turn the material over to defendants within a short time frame, generally about 60 days. The penalty for failing to exercise “due diligence” in acquiring and sharing the evidence can lead to a case being dismissed.

Prosecutors say that five years under the new discovery rules have revealed unexpected problems. “Body cams came online in March of 2019. There was no way to know that that was going to result in 550,000 body cams for Queens alone to review in one year,” Queens DA Melinda Katz told me, estimating that her office handles 1 .7 million discovery files every year. “Dismissal is not always the answer,” she says. “Sometimes, you shouldn’t be able to use the evidence; sometimes that witness shouldn’t be called. Perhaps we should be sanctioned a few days in the courtroom. But dismissal doesn’t always have to be the answer. And the clarity of that would make an enormous impact in criminal justice in the state of New York.”

Judy Kluger, who spent 25 years as a judge and is now CEO of Sanctuary for Families, agrees. ”It’s not easy for a victim to engage in the criminal-justice system. It’s a long, arduous process, and cases are being dismissed and victims are without orders of protection because of the strictures of this law,” she told me. “You might have a pre-arraignment report that is not given over to the defense on time. That can result in a draconian remedy of dismissal. What I think should happen is there should be proportional sanctions that encourage and require the prosecution to give over the information, but does not result in an automatic dismissal of the cases.”

The exact language hasn’t been published yet, but Hochul is pushing for a change in the law that would give judges leeway to mandate dismissal only when missing or late evidence is “relevant” to a case. (The current standard requires that all “related” evidence is shared.)

On the other side, defense attorneys are worried about a possible return to the days when prosecutors would hide information, or ambush defendants by dumping tons of evidence on them right before trial. “We can never go back to that era where New Yorkers have to defend themselves without access to the evidence against them,” says Martin LaFalce, an assistant professor of clinical law at St. John’s University. “I represented thousands of clients in criminal court, both in local criminal court and in superior court, where felonies are prosecuted. We almost never received evidence at all in local criminal court, so our clients would plead guilty to violations just so they could get back to work, just so they could get back to their families and not have to keep coming back to court.”

LaFalce says prosecutors aren’t necessarily to blame for the high levels of dismissals due to delays. “The one change that we’ve seen is in low-level misdemeanor cases in New York City. And the culprit for that change in dismissal rates is the NYPD,” he told me. “The NYPD has been incredibly resistant to providing evidence to prosecutors’ offices, and that resistance has contributed to an increase in dismissals in low-level cases and in New York City.”

Hochul has designated hundreds of millions of dollars to help prosecutors keep up with the flow of evidence, and tirelessly crisscrossed the state and cajoled so many political figures that her supporters now include unlikely allies like former governor George Pataki and the Reverend Al Sharpton.

After weeks of back-and-forth, Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie has agreed in principle to approve changes to the law. Depending on the final language, Hochul will be able to claim an important victory by holding fast to her position in a town where nearly every program, law, and political belief is subject to being watered down or bartered away.

“I just want more people to understand why I’m doing this, why this is so important. It’s not just domestic violence, it’s all crimes. People need to be held accountable for what they did,” she told me. “I held firm on bail reform as well. Anything that has to do with the safety of New Yorkers who are feeling this sense that we don’t care about them, that we’re not looking out for them; they’re afraid to walk the streets, take our subways, have their kids walk home from school. I’m a mom. It is personal to me. The safety of every New Yorker is always going to be personal to me.”